Georgia State's AD said human error caused false positives, the lab's director says otherwise

'Everyone is entitled to a bad day and we chalk this experience to that.'

Georgia State was literally loading its buses on Friday, Sept. 25 to play a road game at Charlotte when the game was postponed. Georgia State had received four positive test results for COVID-19 and contact tracing had eliminated 17 other players, plus two coaches. The school sent out a four-sentence press release just after 2 p.m., stating it had postponed its Week 4 game “out of an abundance of caution.”

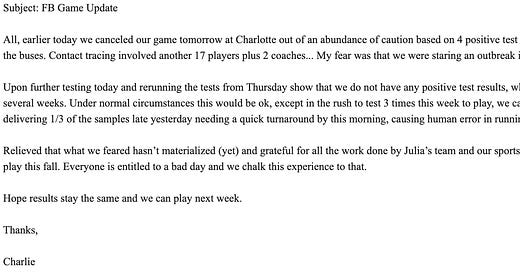

“My fear was that we were staring an outbreak in the face...,” Georgia State Athletic Director Charlie Cobb wrote in an email, which was obtained by Out of Bounds, that was sent the night of the postponement to Georgia State University President Mark Becker, Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Wendy Hensel and other university administrators.

Georgia State conducted more tests on Friday and re-examined its tests from Thursday, which showed that the program didn’t have any positive tests. The program had been without any positive cases for the previous few weeks.

In the email, Cobb accepted some culpability on Georgia State’s part for the false positives.

“Under normal circumstances this would be ok,” Cobb wrote, “except in the rush to test 3 times this week to play, we caused undue stress on the lab by delivering 1/3 of the samples late yesterday needing a quick turnaround by this morning, causing human error in running the tests.

“Relieved that what we feared hasn’t materialized (yet) and grateful for all the work done by [Dr.] Julia [Hilliard]’s team and our sports medicine staff to allow our teams to play this fall. Everyone is entitled to a bad day and we chalk this experience to that.

“Hope results stay the same and we can play next week.”

You can read the full email below.

(Click the image below to open in a new window)

A Georgia State spokesman told Out of Bounds that the athletic department uses the university’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified (CLIA) lab – Georgia State’s Viral Immunology Center – to process its tests. CLIA regulates federal standards for all U.S. facilities that “test human specimens for health assessment or to diagnose, prevent, or treat disease,” per the CDC.

However, while Cobb said the late delivery of samples caused “undue stress” and human error in processing the tests, Dr. Julia Hilliard, the director of Georgia State’s Viral Immunology Center and a professor of biology, told Out of Bounds in an email, “The sample classified by the laboratory director last Friday had no obvious issues, which means there was no identified human error.”

This could be a matter of semantics, with Cobb potentially referring to the false positives as an error that was, well, by made a human, while Hilliard brings a medical lens to the term “human error.” A page on the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s website that discusses scientific error says, “Human error is due to carelessness or to the limitations of human ability. Two types of human error are transcriptional error and estimation error.”

A Georgia State spokesman said the school tested three times last week – on Monday, Wednesday and Thursday – in accordance with Conference USA policies. The university spokesman said the team wasn’t able to adjust its testing timeframe after last week’s false positives because testing is typically conducted right after practice in the late morning or early afternoon.

Since Georgia State is scheduled to play at home against East Carolina in Week 5, the program’s tests this week were scheduled for Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

“You want to do the tests as close to the Saturday game to increase the chances that no one has contracted COVID,” the spokesman said.

Dr. Hilliard told Out of Bounds that it generally takes, at a minimum, four to five hours to process and classify up to 100 samples (roughly the size of a football team). You can see, especially for a road team, how there could be a time crunch if samples are delivered late on a Thursday, needing to be processed early enough on Friday so that the team can leave town and arrive at its opponent’s campus at a reasonable hour before Saturday’s game.

According to Dr. Hilliard, the possible results of a sample include:

Invalid: “if the sample content is insufficient.”

Positive: “if the sample contains sufficient viral markers.”

Inconclusive: “if the sample has low viral copy numbers.”

Negative: “if the sample has no detectable viral markers given the limits of the test.”

Dr. Hilliard thoroughly explained the testing and classification process in an email:

Last Friday we provided results from back-to-back assays on players from two sets of samples, one set obtained Thursday and another set from Friday morning. We reported no human errors with the test results provided to the team physician. Because of the importance of the game scheduled, I discussed the ways in which I resulted the player's samples so he could use his clinical judgment to make decisions for each player. The clinical laboratory director has the final responsibility to make a decision that is clinically comprehensive and not simply a technical or machine calculated value so that an attending physician can make the best decisions for the health of each person tested. With even known positive samples, it is well known in clinical laboratories that there is an approximately 60% chance of identifying the sample correctly under the best of conditions due to a wide variety of events that can impact the final diagnosis, including chain of custody issues, temperature, freeze-thawing, storage, logistics, and even current rate-of positivity.

Dr. Hilliard said there are clinical staff members at her lab who audit each sample at each step to look for potential Type 1 and Type 2 errors.

“A Type 1 error includes technical errors that can be caused by machine settings, sample handling and logistics, failed standards, etc,” she said, “whereas a Type 2 error suggests a fundamental failure of a test and includes analysis of the acceptable range of variation in day-to-day test values of the standards or control samples used to evaluate the efficacy of the test.”

She said that any sample for identifying SARS-CoV-2 using the assay used by Georgia State’s Viral Immunology Center last week has a 34 to 80 percent sensitivity depending on factors that include the duration of the infection, viral load and potential for Type 1 errors.

“Sadly, there are currently no diagnostic tests that provide 100% sensitivity given technological limitations of the day,” she said. “Two different laboratory directors may classify the same sample differently depending on many factors.”

That perspective from Dr. Hilliard reinforces some current medical challenges as they pertain to college athletics during the pandemic, in that there’s not always a consensus of opinion. Reasonable people can disagree based on different interpretations of the same facts and data. In college football, there won’t always a clear-cut answer for who should be, say, the No. 4 seed in the College Football Playoff.

Why should science be any different?

“I think it’s a great comparison,” Dr. Michael Ackerman of the Mayo Clinic previously told Out of Bounds, “because, really, in what you’re doing is you and another colleague are sizing up the same data set, presumably, and through the lens in which you size it up, you’re coming with a different conclusion and that is just also true in science and medicine when there isn’t an obviously correct answer.” The day the Big Ten and Pac-12 postponed fall sports, Ackerman was invited to the Big 12’s Zoom call to discuss the potential impact of COVID-19 on the heart and Ackerman said, “maybe the weight of the heart lessened enough on their balancing scales” after he provided his perspective.

The next day, Oklahoma State AD Mike Holder credited Ackerman and West Virginia University President Dr. Gordon Gee as the reasons why the Big 12 is playing fall sports.

“So when the answer is so obvious that you actually don’t need a committee to decide, then you don’t need a committee to decide,” Ackerman said. “But when there is grey and you’re processing data in real time, you are assessing the significance of that data set with a variety of uncertainties attached to it in real time, also in the setting of a lot of emotion and a lot of energy and a lot of COVID-19 pandemic crazy that we’re surrounded by. Then it becomes not just objective but subjective.”

Every Saturday, college football fans will pick up their TV remote and choose which games to watch based on factors including the AP Top 25 poll rankings and the records of the teams involved, the line in Vegas, and a game’s conference and national title implications. The rankings set by the current week’s AP poll were established by the collection of individual ballots from 62 AP poll voters, each of whom evaluated a group of 130 FBS teams and ranked the top 25 based on their records and resumes.

At every level of the sport, college football stakeholders, ranging from fans, to media members, to coaches, are making decisions – often times in conflict of their peers – based on their interpretation of common data sets, whether it’s about the down and distance, score, a team’s record or its upcoming schedule.

Behind the scenes, doctors and team physicians are doing the same thing, whether they’re sharing their medical perspective with FBS conferences on the potential heart effects from COVID-19 and whether sports should even be played at all during the pandemic, to the classification of a diagnostic test, which could determine if a player can compete in a game or if that game can even happen.

As Georgia State AD Charlie Cobb said in his email to university administrators, “Everyone is entitled to a bad day and we chalk this experience to that.”

Sometimes a fan will choose to watch No. 1 Clemson take a 27-0 halftime lead against Wake Forest, when there’s actually a better game on TV on another channel.

Sometimes a media member will rank LSU (0-1) No. 7 in an AP poll ballot and Mississippi State (1-0) at No. 22, even though the latter beat the former by 10 points on the former’s home field.

Sometimes a coach will call a fake punt on 4th & 11 near midfield during a tie game, late in the fourth quarter of the SEC Championship, thinking he can sneak his versatile, backup quarterback onto the field as the punt protector, even though multiple opponents sniffed out the trick play immediately.

And sometimes, a lab director or physician who’s facing a diagnostic classification that doesn’t have a 100-percent sensitivity will misclassify a sample, leading to false positives that postpone a game.

Recap of last week’s newsletter

Click the image below to read.

“Coach Freeze told me personally in Oxford that [former Southern Miss President] Dr. [Martha] Saunders had told him that he was her number one choice back at that time. Freeze said that he was headed to Southern Miss until Archie [Manning] and Ole Miss came calling.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Connect on social media

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.