On field storming, the institutional responsibility to protect a community from itself and the 'legitimacy' of the college football season

A football team is part of the community, and Notre Dame's field storming put both at risk. It may take negative consequences for the former for the school to realize the effect it has on the latter

Since the College Football Playoff (CFP) started in the 2014 college football season, 11 different schools have earned the 24 total playoff bids, with Alabama, Clemson, Oklahoma and Ohio State combining for 17 playoff berths, or 70 percent of the total.

Seven other schools have appeared in the playoff once, including Notre Dame, which beat top-ranked Clemson 47-40 in double overtime on Saturday.

That means that 8.4 percent of the college football teams that compete at the FBS level (11 out of 130) have finished one of the last six seasons ranked in the top four of the selection committee’s final rankings, but in each of the last five years, the Big Four has claimed three of the four spots in the playoff, leaving the other 126 schools to fight for the fourth spot, which is left for a school like an LSU, a Notre Dame or an Oregon.

This is the 10,000-foot view of the sport’s current hierarchy, its postseason and the national dominance by a handful of schools, which will be preserved in the record books and on whatever the 2070 version of Wikipedia will be.

Notre Dame’s win over Clemson in Week 10 was arguably the game with the most potential, to date, of disrupting this season’s bottom line – both the bottom line, literally, in terms of revenue, as well as the box-checking that comes with holding some sort of irregular, regular season that is then followed by conference championship games, the selection of four playoff teams and then the naming of a national champion that’s deemed legitimate.

In the eyes of many, checking those boxes would probably be enough to qualify the 2020 college football season as a success, which says nothing of the experience so far this season for FBS independent UMass, which has played just two games and lost both by a combined score of 92-0, or schools such as FAU, FIU and Houston, which have repeatedly had games postponed or canceled.

No, the bar for success for many fans will be the playing of two College Football Playoff Semifinals and then a national championship game, with the playoff likely featuring some combination of Alabama, Clemson and Ohio State, plus the fourth playoff team de jour. Maybe a team like Notre Dame.

But if a team on a potential playoff trajectory is thrown off course due to the pandemic – if the virus treats a national championship contender like it has treated the seasons of so many Conference USA schools – then that’s when it becomes time for everyone to start asking the hard questions. There would be questions about the perceived legitimacy of the season and the overall value of a pandemic-altered season, if a choppy fall results in a national champion that is questioned, if not rebuked, by many fans.

Clemson lost to Notre Dame after playing without former Heisman Trophy betting favorite and presumptive No. 1 pick in the 2021 NFL Draft Trevor Lawrence, who tested positive for COVID-19. A two-loss team has never made the playoff and while one of the CFP protocols states that the selection committee will consider “other relevant factors such as key injuries,” a second regular-season loss could potentially keep Clemson out of the ACC Championship Game and a potential loss in the conference championship game would undoubtedly leave the Tigers out of the playoff as a two-loss team that didn’t win its conference championship.

A hypothetical playoff without Clemson, which was ranked No. 1 in the AP poll from the preseason through Week 10, in a season in which at least one Clemson loss could potentially be explained away due to Lawrence’s COVID-19-related absence, could chip away at the legitimacy of the playoff, and therefore the season, for some fans.

Then there’s Notre Dame, which pulled off its biggest win in coach Brian Kelly’s 11 seasons in South Bend, only for the school’s fans to storm the field, as college football fans do on an annual basis, except that doing so in 2020 comes with more risks and higher stakes.

When the MAC was finalizing its medical protocols as the conference worked to return to the field, Northern Illinois’s head team physician Dr. Brian Babka wrote to the school’s athletic department, “The most risk is on our own sidelines. Even the best block is only held for an average of 2 seconds.”

A field storming presents both the close contact of a strong, in-game block and the prolonged gathering that might exist on a team’s sideline.

The cruel irony is that if the on-field celebration at Notre Dame Stadium proves to be a super-spreader event, which we can all wholeheartedly agree that we hope does not happen, then the Fighting Irish’s promising season could potentially be disrupted.

Hopefully this all turns out to be misguided hand-wringing and that Notre Dame’s testing protocols prevented potential disaster.

Notre Dame has already had one game postponed – against Wake Forest in Week 4 – due to positive tests within the Irish’s program and the resulting contact tracing, and for an ACC team to be eligible for the ACC Football Championship Game, it has to play a total number of conference games that’s within one game of the average number of conference games played by all conference teams, such that the average number is rounded up or down at 0.5 of a game.

For example, if the average number of games played in the conference is rounded up to 10 games and a school only plays eight, it wouldn’t be eligible for the ACC Championship Game. Right now, Wake Forest has played five conference games, while seven ACC schools have played seven conference games.

Of course, the health and safety of a university’s students, faculty and staff, as well as that of the surrounding community and the viability of the local public health system, should be far more important than a football team’s regular-season schedule or its postseason aspirations. But if receiving checks from television broadcasts and the ability to compete for conference and national championships were two of the driving forces for having a college football season, as they seem to have been, then it’s surprising that Notre Dame’s leadership would potentially put those checks and trophies at risk – let alone the health of the local campus community – by permitting the circumstances that allowed for a field storming.

It’s not as if Notre Dame didn’t see the field storming coming, either.

“I just want you to know. When we win this thing, the fans are going to storm the field,” Brian Kelly reportedly told his team during the walkthrough on Saturday morning before the game, according to ESPN. Notre Dame Athletic Director Jack Swarbrick acknowledged to ND Insider that there were three possible outcomes – a Clemson win, a decisive Notre Dame win or a close Notre Dame win – and that the third result was “one where you know you face the challenge of a field rush.”

This is the school that has allowed 10,000-plus fans inside its gates for home games, only to publicly shame them on the jumbotron when they weren’t standing six feet apart, as if it was some cheeky, in-game marketing promotion.

This is the real-life embodiment of so many memes – the Garfield one, the one from SpongeBob, the one from that Netflix show – all of which express that the person responsible for something bad, the person who everyone is looking for or looking to blame, is actually you.

Notre Dame is Garfield. Notre Dame is the Tattletale Strangler from SpongeBob. Notre Dame is that guy in the hot dog costume.

“We’re all trying to find the guy who did this,” Notre Dame says as students pack the field, while it counts more than 11,000 gate receipts.

Sure, Notre Dame students were the ones who stormed the field.

The ushers and stadium security were put in an impossible situation and I guess, in a warped sense, they technically “didn’t stop them,” if you want to make the flawed argument that the stadium staffers who are often in a higher-risk category when it comes to the virus should’ve prevented the swarm of screaming students from entering the field. Notre Dame AD Swarbrick told ND Insider that the school hired “a lot of extra security, obviously, extra police detail and extra ushers.”

It should be noted that Swarbrick said the university voided more than 500 student tickets prior to the game for students who potentially posed a health risk at the game:

In the normal course, as we did for this, any student who presented a particular risk was not allowed in. So we voided over 500 tickets of students who either were in quarantine for close contact, were in isolation for having tested positive or failed to show for a surveillance test.

But the blame for any potential fallout from the field storming falls squarely on Notre Dame’s administration – both those in the athletic department and at the university level who determined the stadium’s attendance capacity, and who designed and implemented the protocols that were designed to keep everyone safe.

When you don’t take a puppy outside to go to the bathroom for hours and then the puppy pees on the carpet, sure the dog is the one that peed in the house, but who’s really the one at fault? Hint: it’s not the puppy.

If a parent packs spaghetti with marinara sauce for lunch for a second-grader on class picture day and the second-grader gets a stain prior to the pictures being taken, the parent could be disappointed with the second-grader for making a mess, but the parent also better acknowledge the role the parent played in Prego sauce ending up on a white shirt.

What happened at Notre Dame Stadium was Murphy’s Law in action: anything that can go wrong will go wrong.

Notre Dame gave college students the chance to be college students.

It’s worth putting Saturday’s field storming in the larger context, after Notre Dame President Father John Jenkins penned an opinion column in The New York Times in May with the headline “We’re Reopening Notre Dame. It’s Worth the Risk.” Jenkins later tested positive for COVID-19 after attending a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden in September, after which, several attendees, including President Donald Trump, tested positive.

A student judiciary council formally sponsored a proposal for Jenkins’s resignation after a petition received the requisite number of signatures, but the Notre Dame student senate voted against the resolution, according to the student newspaper The Observer. A measure of disappointment against Jenkins was passed by the Notre Dame faculty senate after a motion of no-confidence failed, per WSBT-TV.

In his column for The New York Times, Jenkins wrote:

Indeed, keeping healthy relatively small cadres of student-athletes, coaches and support staff members is a less daunting challenge than keeping safe the several thousand other people in the campus community.

Fans in the stadium, however, are a different matter. Fighting Irish fans regularly fill Notre Dame Stadium’s 80,000 seats. I see no way currently to allow spectators unless we restrict admissions so that physical distancing is possible.

Our focus to this point has been on restarting our educational and research efforts, and we will soon turn to answer the question of how many games we will play, when we will play them and how many fans will be in the stadium.

Jenkins wrote that keeping athletes and coaches safe would be less challenging than it would be to keep the entire campus community safe, but the literal groundswell on Notre Dame’s field Saturday night was further evidence that those two groups – athletes and the rest of campus – aren’t mutually exclusive, especially when the social distancing he said would be required in the stands goes out the window in a field storming.

A football team is part of the campus community.

It is the campus community.

This is the reality of college football in 2020, when the number of positive tests and the number of players being held out of competition due to contact tracing is often directly related to how much of a handle the local community has on the virus.

In Week 10 of the college football season, there were just that many games postponed or cancelled – 10. It’s probably not a coincidence that the first week of November, which saw the highest numbers of new cases of COVID-19 in the country (a record 132,797 new cases nationally on Nov. 6, per The New York Times), also saw the highest number of college football games postponed or canceled in a week so far this season.

They were caused by schools and communities in California, Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Texas, Utah and Wisconsin, many of which are located in cities and counties that are facing some of the highest COVID-19 case totals per capita in the country.

When you see the number of cases last week, relative to population, in cities such as Madison, Salt Lake City, and Colorado Springs, as shown below in a graphic from The New York Times, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the college football programs in those communities were also affected by the virus.

In a meeting among Power Five doctors on Aug. 4, University of Washington team physician Dr. Jon Drezner said it will be too difficult to isolate athletes because they don’t have an NBA-type bubble, according to notes from the meeting that were obtained by Out of Bounds.

The football team is part of the community, and when the community is at an increased risk of exposure to the virus, so is the football team, even if it has the resources to conduct daily testing, like the Big Ten and Pac-12 schools do.

Three of the 10 games that were postponed or canceled in Week 10 involved teams from the Big Ten or Pac-12. Rapid, daily testing only lets schools know if someone has the virus sooner, which allows for more immediate contact tracing and quarantine efforts, but daily testing doesn’t inherently prevent someone from catching the virus, especially if the local community is facing a high number of cases relative to its population.

"With COVID being as it is, we've got to get off the field and get to the tunnel," Brian Kelly said after Saturday’s game, according to ESPN. "Now I beat 'em all to the tunnel. So that didn't go over so good, but they reminded me that I did tell them that, so my skills of prognostication were pretty good today."

As of Sunday, over the previous week, Indiana’s St. Joseph County, where South Bend is located, averaged 190 cases daily and an average of 70 cases per 100,000 people, according to The New York Times.

Roughly one in 22 people in the county has had the virus, according to The Times.

Notre Dame reportedly had 11,011 fans in attendance on Saturday, which means if we apply The New York Times’s one-in-22 average for the county, roughly 500 of them have had the virus at some point. Hopefully as many of those cases as possible can be talked about in the past tense, rather than the present.

“We encouraged them to get off the field quickly,” Swarbrick told ND Insider, regarding Notre Dame’s players. “Not all of them did it. We’ll see whether that represents increases and a difference in our testing experience this coming week.”

In a surreal moment Saturday night, the country got to watch live as a potential future contact tracing event took place in realtime on NBC.

In an interview with Out of Bounds in July, Dr. Ron Waldman, a professor of global health and an infectious diseases expert at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health, said, “This country has to get to grips with focusing its attention on the virus and on reducing transmission of the virus. When that happens, everything else can move forward. The economy can move forward, schools can move forward, athletics can move forward. And I don’t know why everyone’s attention is not fixed on reducing transmission in the community.

“That’s the obstacle to allowing of these other things to go forward.”

It’s a quote that I’ve shared several times, because it has stuck with me and unfortunately, it still resonates four months later.

In a field storming predicted by the school’s own head coach and outlined by its athletic director as a possible outcome, Notre Dame was ill-prepared to prevent hundreds, if not thousands, of students from celebrating on the field, leaving the school’s 75-year-old public address announcer Mike Collins to plead with the crowd, according to Sports Illustrated:

“We want everyone to be safe and sound here,” Collins intoned. “Please make your way off the field. … Use any open aisle, please. … And if the ushers could help out a little bit, that would be helpful.”

Nobody listened.

Three and a half hours south of Notre Dame, Indiana has compiled an undefeated record and a top-10 ranking of its own while playing only in front of the family members of players and coaches, in accordance with Big Ten protocols.

Good luck trying to quantify the value, or relative lack thereof, of home-field advantage in 2020, but Notre Dame doesn’t have to look far for a couple of examples of top-performing teams that haven’t been hindered by the lack of a home crowd this season. The schools and conferences that are allowing fans are trying to maximize revenue, and health and safety at the same time, and when a field storming happens – probably the worst-case scenario for a football game this season from a public health perspective – the former comes at the expense of the latter.

The potential risks to the local community should be enough of a sell for schools to take their attendance restrictions and gameday protocols seriously, but if speaking “football” is what’s required to get the point across to administrators, then the reality is that Notre Dame, which is now ranked No. 2 in the country and sits alone in first place in the ACC, potentially put its players, its next game and all that comes with an undefeated start to the season, in jeopardy.

And that’s because Notre Dame put the health of the local campus community in jeopardy. 2020 has shown us that the football team is one and the same with the community, and health and safety protocols be damned when your school hosts, then beats, the No. 1 team in the country.

Recap of the last newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

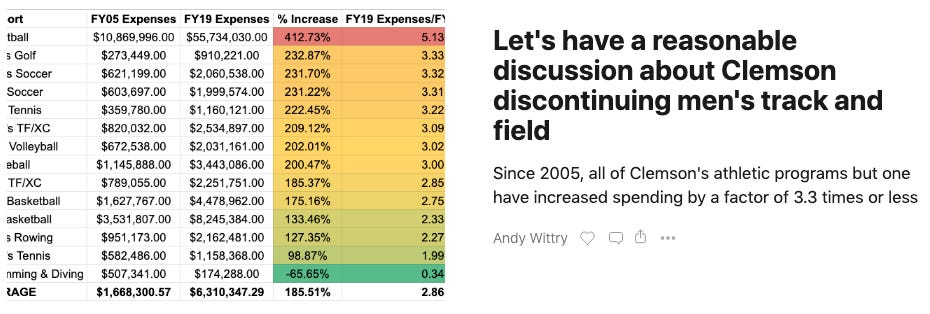

“Clemson’s athletic department has decided that an increasing percentage of its budget goes to football, which is all well and good, but it has refused to say the quiet part out loud, which is that it costs a lot of money to maintain a college football superpower and that when a once-in-a-century pandemic comes along, some other athletic program will be the first to make a sacrifice – and to be sacrificed, if it comes to it.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Connect on social media

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.