Freshman and transfer international athletes are affected most by move to online classes

'Speaking purely from athletics, no none of our new international student-athletes (freshmen or transfers) will be on our campus this fall'

In response to a question asked on the University of Nevada’s 2019-20 end-of-season athlete survey, which read, “How could we improve the overall experience for student-athletes at Nevada?” one Wolf Pack athlete answered, “be more clear about what is going on and help internationals with problems they face because they do not know how America works.”

That answer was written on Feb. 27, 2020. In the six months since, college coaches and administrators have had a lot more to explain to their international athletes about America.

Would you choose to go to a country that has more confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths than the country you’re currently in? Would you even be allowed to enter that country on a visa? And if you’re allowed, what hoops would you have to jump through to make your entry and continued visa status possible? Is it even worth it?

Those are some of the questions that face international athletes who attend college in the United States. Who knows which of those questions is the most difficult to answer, or which answer comes with the most qualifiers.

It will be addressed in further detail later in the newsletter, but the potential, ongoing worries for international students about their health and safety, and visa status have been added to a list of concerns that many students in their position already have about studying in the U.S., including fear of gun violence, bigotry and discrimination, and being away from their friends and family.

‘We are asking students to come back to the U.S. from countries where COVID-19 case-loads are significantly lower’

Before the MAC suspended fall sports competition on Aug. 8, its member schools were tasked with navigating the financial and scheduling fallout from the Big Ten announcing conference-only fall schedules, as well as the Ivy League and Patriot League cancelling their fall sports. In preparation for a meeting among the MAC’s university presidents on July 11, Kent State President Todd Diacon asked Athletic Director Joel Nielsen to report how many of the university’s games would be canceled due to the decisions made by the Big Ten, Ivy League and Patriot League, and how many current Kent State athletes are international students, according to an email obtained by Out of Bounds.

Later in the email thread, Kent State Faculty Athletics Representative Kathy Wilson, who’s the Chair of the Economics Department, emailed Diacon:

“I would just weigh in on a couple of thoughts in terms of student-athlete well-being particularly related to international students. If we begin the semester but end up needing to close, I am concerned with our international students’ ability to get back to their home countries; we may need to provide housing for them similar to what we did in the spring. Second, I do think it is a consideration that we are asking students to come back to the U.S. from countries where COVID-19 case-loads are significantly lower, which increases their risks. While there are many factors to consider, I think these are worth being included in that mix.”

By the way, the need to provide housing for international students in the case of if, and when, a university moves to online classes is something the University of North Carolina addressed Monday when it announced it was shifting all undergraduate instruction to remote learning starting Wednesday. “Residents who have hardships, such as lack of access to reliable internet access, international students or student-athletes will have the option to remain on campus,” read North Carolina’s news release.

Kent State’s AD Nielsen later sent President Diacon a spreadsheet of the school’s canceled fall sports contests, which included the following notes at the bottom of the spreadsheet, regarding international students:

Varsity sport credit is considered a face-to-face course, but there are concerns on how this course may be viewed by a border agent. We are working to find major specific courses for each student. Athletic academic counselors are partnering with college advising offices to accomplish this task.

Student-athletes are being briefed on their course schedules and how to describe their face to face class to a border agent.

Recommendations will be provided to print a class schedule, proof of athletic aid, and any other documentation they have showing they are face-to-face at the Kent campus at the border.

Many of our incoming student-athletes will likely be deferring enrollment to spring term due to lack of flights and/or inability to obtain an F-1 visa.

If border agents agree with Kent State’s assessment, athletics could potentially help some international students enter the U.S. for the fall semester, if it’s their last resort if all of their classes are moved online.

Kent State currently has international athletes from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Jamaica, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom, according to the spreadsheet.

While the names and personal details of the athletes were redacted in the spreadsheet, it appeared that roughly 45 Kent State athletes who are international students were residing in their home countries in mid-July compared to just four international athletes who were residing in the U.S., so the majority of the school’s athletes had to or will have to deal with re-entering the country after the email was sent – if they try at all.

Even before the MAC suspended fall sports, which once again, would be considered a face-to-face course according to Kent State, the spreadsheet from the university expressed concerns about its international athletes’ ability to enter the U.S. in order to comply with the current U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) regulations.

In a document titled “Frequently Asked Questions for SEVP [Student and Exchange Visitor Program] Stakeholders about COVID-19” that was published by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement on Aug. 7, the answer to one FAQ reads, in part:

DSOs [Designated School Officials] should not issue a Form I-20, “Certificate of Eligibility for Nonimmigrant Student Status,” for a student in new or initial status who is outside of the United States and plans to take classes at an SEVP-certified educational institution fully online.

As a result, new or initial nonimmigrant students who intend to pursue a full course of study that will be conducted completely online will likely not be able to obtain an F-1 or M-1 visa to study in the United States. If a nonimmigrant student was enrolled in a course of study in the United States on March 9, 2020, but subsequently left the country, that student likely remains eligible for a visa since the March 2020 guidance permitted a full online course of study from inside the United States or from abroad. The March 2020 guidance applies to nonimmigrant students who were actively enrolled at a U.S. school on March 9, 2020, and otherwise complying with the terms of their nonimmigrant status.

This means that returning nonimmigrant international students attending a college or university in the U.S. will be able to return to school even if they’re taking online courses, but freshmen or new international athletes will likely not be able to get a visa if they’re taking fully remote instruction.

The ICE document further clarified this point:

For returning students who have remained in the U.S.: “Per the March 2020 guidance, yes, nonimmigrant students may remain in the United States to engage in full course of study online if they have not otherwise violated the terms of their nonimmigrant status.” The document said that even if a nonimmigrant student’s school switches from in-person or hybrid instruction to online courses, nonimmigrant international students can remain in the U.S.

For new students: “Nonimmigrant students in New or Initial status after March 9 will not be able to enter the United States to enroll in a U.S. school as a nonimmigrant student for the fall term to pursue a full course of study that is 100 percent online.”

If not for a lawsuit filed by Harvard and MIT against the federal government, which were followed by plans of additional lawsuits from other universities, the path to a stateside education for returning international students during the 2020 fall semester could’ve been blocked, too, in addition to the current policies for freshmen and transfers.

In an email sent July 28, Manfred van Dulmen, Kent State’s Interim Associate Provost for Academic Affairs and the chair of the university’s Reopening Steering Committee, wrote, “As you may know, in response to legal action and appeals from hundreds of college and university leaders, including Kent State University, the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) has retracted its guidance from July 6.”

Even after the federal government relaxed its visa restrictions after the lawsuits were filed, U.S. Embassies were not yet fully functional. As noted in an email sent to Texas Tech’s international students by the Office of International Affairs in mid-July, “U.S. embassies around the world are still closed for regular visa processing. This may make it difficult for international students to re-enter for the fall semester to resume in-person studies.”

The U.S. Embassy in Madrid, Spain, as just one example, canceled immigrant and nonimmigrant visa appointments as of March 12, but on July 20 it began processing F, M and some J visas for those who had urgent travel requests.

The email from van Dulmen, the Kent State Interim Associate Provost, said that new, incoming international students who didn’t get a visa or who elect to stay in their home country for the fall semester “can enroll in any number of classes remotely or defer their admission to the next available term.”

There are also risks involved for international students who try to enter the U.S. with a student visa after the first day of their university’s fall classes. “Essentially, their approval of entry will be entirely dependent on the discretion of the specific border agent they encounter,” wrote Texas Tech Senior Associate Athletics Director of Academics and Eligibility Greg Glaus in an email on Aug. 12. “I have a call into the Office of the Provost to discuss a potential academic letter of support that could detail academic accommodations and our support of their late arrival, but there is no guarantee that it would help.”

On July 7, Glaus wrote that Texas Tech’s international athletes would be able to maintain their visa status as long as they aren’t declared in an online-only degree program or enrolled in a fully-online fall 2020 schedule.

There’s potentially as many students affected as there are ACC/Big Ten/SEC football players

Strictly from a higher education perspective, those who could be most affected by the U.S.’s inability to stop the spread of COVID-19 are international students.

How many international athletes could potentially be affected by the combination of ICE’s latest student visa regulations and universities that have moved to online courses?

It’s probably a bigger number than you realize. The international athletes you’ll see on Saturdays in college football are typically limited to a handful of Aussie punters or maybe a former rugby player or track and field athlete from Europe who was converted into a lineman, but non-revenue sports such as field hockey, golf, soccer, swimming and diving, and tennis rely on a significant population of international athletes.

The NCAA Demographics Database indicates there were 20,920 “nonresident alien” athletes across the NCAA’s three divisions during the 2018-19 school year, which is the most recent year for which data is available. In Division I alone, there were 11,719 international athletes who were in the U.S. on a student visa and 2,845 international athletes in the Power Five conferences.

Using the NCAA’s race/ethnicity designations, “nonresident alien” was the fifth-most represented group among NCAA athletes in 2019, with a total that was just nine athletes fewer than the number who identified their racial/ethnic background as being of two or more races (20,929 athletes).

To oversimplify the math, if you divide the total NCAA international athlete population by four (to estimate how many international athletes are incoming freshmen), roughly 5,230 NCAA athletes are freshmen, who could be affected by the U.S.’s student visa policies during the 2020-21 school year if their individual course load is made up exclusively of online classes. As a point of reference, there were 5,240 football players who competed in the ACC, Big Ten and SEC in the 2018-19 season, according to the NCAA’s database.

While the will-they-or-won’t-they-play discussion surrounding the FBS football season is the most popular topic in college athletics right now, just remember that for every ACC, Big 12 or SEC football player who’s currently scheduled to play this season for a Power Five school, there’s an NCAA athlete who’s potentially facing concerns about the status of their visa and whether they can even make it to the U.S. and to their college campus, let alone play their sport.

That comparison doesn’t even include international athletes who transferred after last school year, who could also be affected due to the same ICE and visa policies. If you set aside athletics for a second and expand this conversation to international students at large, universities that have announced virtual learning this fall could collectively miss out on tens of billions of dollars in tuition and room and board.

CNBC put the potential combined losses at $41 billion.

‘None of our new international student-athletes (freshmen or transfers) will be on our campus’

For universities without fall sports, are varsity sports still considered to be a face-to-face course by the university? More importantly, are they considered a face-to-face course in the eyes of a U.S. border agent?

Well, it might vary on a school-by-school and agent-by-agent basis.

At San Diego State University, “membership on a varsity athletics team does not count as a unit bearing activity or as coursework,” the university told Out of Bounds in an email. “Therefore, it will not count as a ‘face to face’ course for the purposes of applying for an F-1 visa.”

A spokesman for the University of Texas also said varsity sports wouldn’t count for the purposes of their visas and that international students would need to enroll in face-to-face or hybrid courses.

The entire California State University system, which includes universities such as Fresno State, Long Beach State, San Diego State and the Cal State schools that have campuses in Bakersfield, Fullerton and Northridge, will conduct most of its classes virtually this fall, with the exception of some lab-based and clinical courses.

San Diego State University told Out of Bounds it will offer “certain lab, art studio, and performance-based courses in person, including clinical offerings that are required for licensure.” Those in-person courses translate to “approximately 7.7% of all classes offered being entirely or partially in-person.”

With a fall semester that will be mostly or completely online for so many students in the U.S. – an online education that comes with its own challenges, by the way – international students who have an online-only semester could have trouble entering or staying in the U.S., if they try to enroll at all.

Out of Bounds contacted 15 Division I universities to ask a version of the following questions:

Will all new international students (freshmen and transfers) at the university be able to enter the country on an F-1/M-1 visa since many or all students will be taking online classes this fall?

Will participation in varsity sports count as a "face-to-face" or in-person course for new international students for the purposes of their visas?

“Speaking purely from athletics, no none of our new international student-athletes (freshmen or transfers) will be on our campus this fall,” Fresno State Senior Associate Athletics Director Frank Pucher told Out of Bounds in an email.

A follow-up request for the number of affected athletes, as well as an interview request for one of five different Fresno State head coaches whose rosters have had multiple international athletes, was not returned.

A spokeswoman for Rutgers University said the university’s international athletes are enrolled in hybrid classes, so all were issued visas. Most of the university’s courses this fall will be offered remotely, with limited in-person classes.

A spokesman for Michigan State, which on Tuesday announced a transition of its in-person and hybrid courses to remote formats, didn’t answer either question, instead offering, “MSU will be working with our international students to make sure they feel welcome and part of our Spartan community, including helping them navigate the complexities of their student visa status.”

A representative from San Jose State University declined to comment.

Previously: ‘You are looking live … at Introductory Accounting here at Kyle Field’

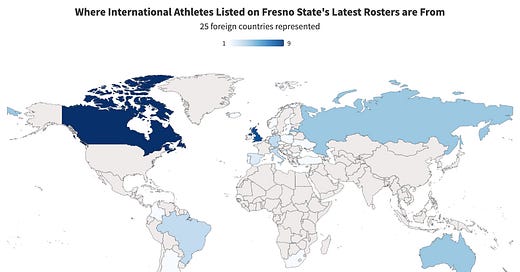

Out of Bounds counted 58 Fresno State athletes who were born in a foreign country and who were listed on their sport’s most recent roster available online, either from the 2019-20 or 2020-21 school year. If you play the percentages (and don’t include potential incoming transfer students), 25 percent of 58 athletes is 14.5, so a rough estimate would suggest between 10 and 20 international Fresno State athletes are potentially impacted by the current ICE policies and the California State University system’s decision to hold mostly online classes.

According to Fresno State’s latest rosters, 13 of the university’s 18 athletic programs had, or will have, at least one international athlete on their latest roster. The Bulldogs’ 2019-20 women’s track and field roster listed a school-high 12 international athletes, while the university’s women’s swimming and diving team had 10 last season.

Here’s a world map that shows the home countries of Fresno State’s international athletes. (Click on the image to open in a new window.)

For the sake of comparison, below is a world map of COVID-19 cases through Aug. 18, courtesy of NPR. Fresno State’s latest rosters include athletes from Brazil, which has experienced the second-most COVID-19 cases and deaths, but the university also has athletes from Canada and Australia, which only had 9,090 and 450 deaths from COVID-19 through Tuesday, respectively, per NPR.

In the words of Kent State’s Faculty Athletics Representative Kathy Wilson, “I do think it is a consideration that we are asking students to come back to the U.S. from countries where COVID-19 case-loads are significantly lower, which increases their risks.”

Click on the image below to open in a new window.

One of Fresno State’s athletic programs was almost exclusively made up of international athletes last season. Seven of Fresno State’s eight women’s golfers last fall were born in a foreign country. In a more prominent sport, the Bulldogs’ women’s basketball team lists five international players on the university’s 15-player, 2020-21 roster.

Even the university’s revenue sports – football and men’s basketball – have athletes who were born in a foreign country. Two members of the football team are from Canada and 6-7, Brazilian guard/forward Leo Colimerio is listed as a member of the Bulldogs’ 2020 men’s basketball recruiting class. Colimerio joins center Assane Diouf, who’s from Dakar, Senegal, as Bulldogs who are from foreign countries.

Previously: Here’s what the college football fan experience could look like this fall

If a school has just one scholarship basketball player who’s an international student, that’s roughly eight percent of its scholarship players. If that player is a freshman or a transfer student, and his or her course load consists entirely of online courses, then the team’s roster of scholarship players could immediately be capped at 92.4-percent roster capacity.

Now imagine a school that recruits heavily internationally, with multiple freshmen and/or transfers who could have trouble getting a visa for the 2020-21 school year.

For this visa/online classes issue to make national headlines in college athletics, it might take a notable men’s basketball program’s roster, which is normally full of international players, getting gutted by the combination of the current ICE regulations and the university shifting to an online-only semester. But if that happens, there will have likely been countless men’s and women’s golf, soccer and tennis rosters that have met the same fate, or worse, but without the same attention.

A spokesman from USC – the kind of big-name school that is more likely to garner major headlines than, say, Fresno State – declined to answer the two questions posed by Out of Bounds directly, instead providing a link to the university’s Fall 2020 website that lists answers to FAQs.

After a couple of clicks and some scrolling, the website reads, “New students, transfer students, students returning from a Leave of Absence (LOA), students traveling to reinstate status, and all other students with an initial attendance or transfer pending I-20 who are currently outside the United States are not eligible to enter the United States and enroll in 100% online classes.” Most USC students will participate in online classes.

Previously: Here’s the impact online classes have on students, according to DI athletes

Perhaps the worst-case scenario for some international students is that they push off college for another year. Another FAQ response on USC’s Fall 2020 website reads, “Undergraduate students could be granted deferrals in specific cases relating to medical issues, religious obligations, required military/national service and, in the case of international students who will attend classes online from another country, the inability to construct a reasonable online course schedule that is compatible with their home time zone.”

International students who have committed to enroll at USC, but who ultimately do not, will forfeit their spot in USC’s 2020 enrollment class and they will have to reapply in the future with no guarantee of admission, according to the website.

The health, immigration and education circumstances in the U.S. leave international students with the options to:

Come to the U.S. (and hope a border agent doesn’t prevent their entry) in order to go to school in a potential COVID-19 hotspot for a watered-down educational experience that’s likely either in a hybrid format or completely online.

Take online classes from an American college or university while living in a different time zone in their home country.

Defer their enrollment at an American college or university, maybe for a year or maybe permanently – if in a semester or in a year they decide there’s a better educational or professional path for them.

Each option comes with its own unique challenges.

On July 30, Kent State Associate Athletic Director/Senior Woman Administrator Amy Densevich wrote in an email that she is “not [making] any changes to international students schedule (as far as moving them from in-person back to remote) until I know they are in the US!”

Once international students are in the U.S., with the visa and border issues behind them, and COVID-19 concerns in front of them, they’ll also have to face other pre-existing concerns that international students have about studying in the U.S., such as gun violence, bigotry and discrimination.

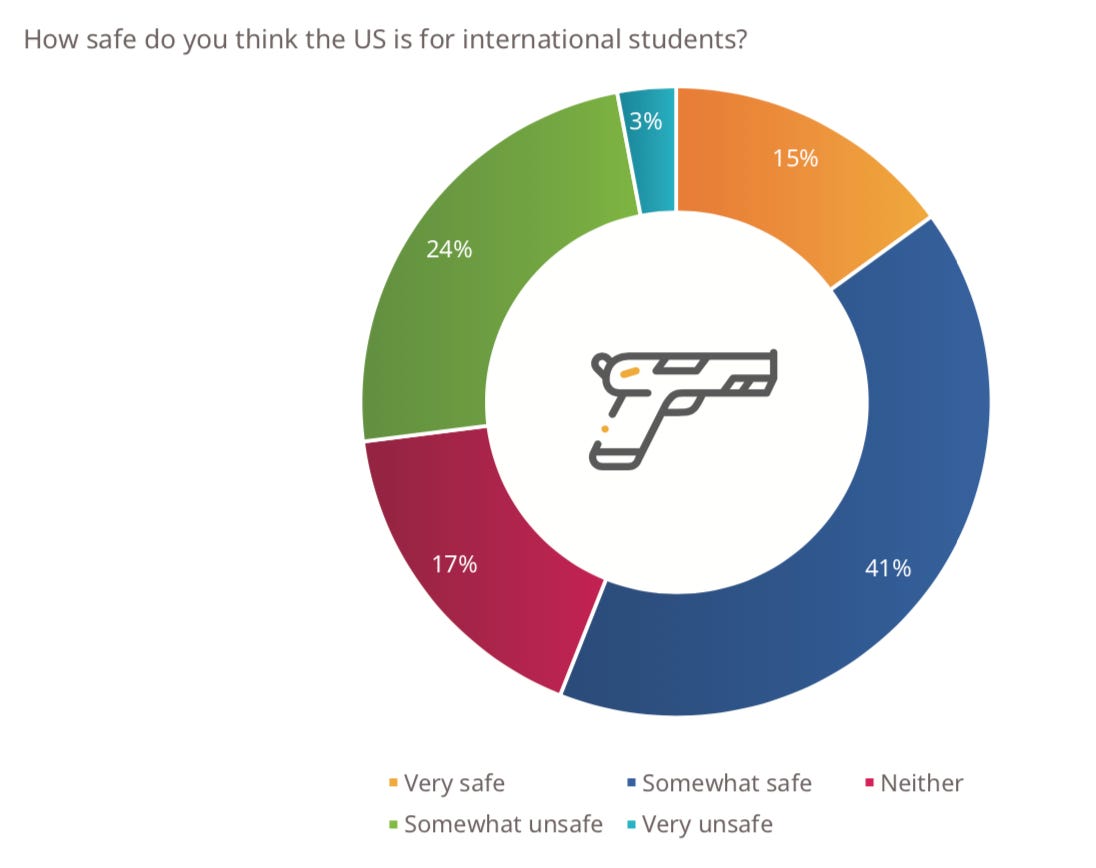

Quacquarelli Symonds (QS), which is “the world’s leading provider of services, analytics, and insight to the global higher education sector,” according to its website, issued its eighth annual International Student Survey (ISS) on June 18, 2020, which featured 78,578 respondents from 196 countries.

Out of Bounds obtained a copy of the 2020 survey, which reported 24 percent of respondents said the U.S. is “somewhat unsafe” for international students, while 17 percent answered “neither” safe nor unsafe, and three percent said “very unsafe.”

That’s 44 percent of the respondents who answered that the safety of international students in the U.S. is neutral or worse.

Two-thirds of the international students surveyed said the increased level of gun violence in the U.S. is a concern and almost 60 percent were concerned about experiencing bigotry or discrimination.

One of QS’ key findings from surveying more than 78,000 international students was that “a significant number of prospective students are put off from studying in the U.S., in response to unwelcoming messages and Trump administration policies.”

After the University of North Carolina, Notre Dame University and Michigan State University announced this week that they are moving to online classes, the pressing question now is how many international students will even make it to the U.S. for fall classes, and what are they sacrificing or risking in the process?

And once they’re here, what kind of experience is waiting for them?

Recap of the last newsletter

Click the image below to read the newsletter.

“Athletes are escorted during a socially distanced, roughly quarter-mile walk from the Campus Recreation Center to the baseball field, which they’ll enter through the right-field gate. The garage doors near left field are opened, with weights moved to an outdoor area in foul territory by the field. Any conditioning is done on the left field turf.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Connect on social media

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.