Athletes, staffers ask for more mental health resources amid budget cuts

"As I went through line items, all I could think about was our kids need these services readily available to them."

Reading time: ~19 minutes

In an open letter addressed to Iowa State fans last week, Cyclones Athletic Director Jamie Pollard took college sports fans behind the curtain for a transparent look at the financial realities facing Iowa State, and other athletic departments, if one or more of the school’s three primary revenue sources – television, donations and ticket sales – decreases or is completely removed from the equation during the 2020-21 school year.

“I feel it is imperative and timely to clarify the reasons why we are doing everything in our power to try and safely play college sports this fall,” Pollard wrote. “Some people have incorrectly framed the issue as safety versus revenue generation. The simple fact is that reality lies somewhere in the middle.”

Pollard broke down Iowa State’s $86 million budget between fixed and variable costs, the latter of which includes a $7-million category called “Academic, Medical & Nutrition.”

Pollard continued:

In addition, the financial disruption caused by not having a football season would have an overwhelming negative impact on the safety and well-being of the 475 student-athletes we support. The revenue generated by the department is necessary to provide the academic, medical, nutritional and athletic support that is relied upon by our student-athletes.

In the face of athletic department pay cuts, employees being furloughed and the doors being shut on entire athletic programs – combined with uncertain revenue sources this fall and winter – off-the-field support for athletes is at stake.

Out of Bounds obtained an email sent to a Power Five athletic director by someone in his department, who expressed the urgency of this dichotomy: there is still a need for more resources, especially for mental health, even though athletic departments around the country are trying to cut their budgets.

‘I believe a breaking point is close’

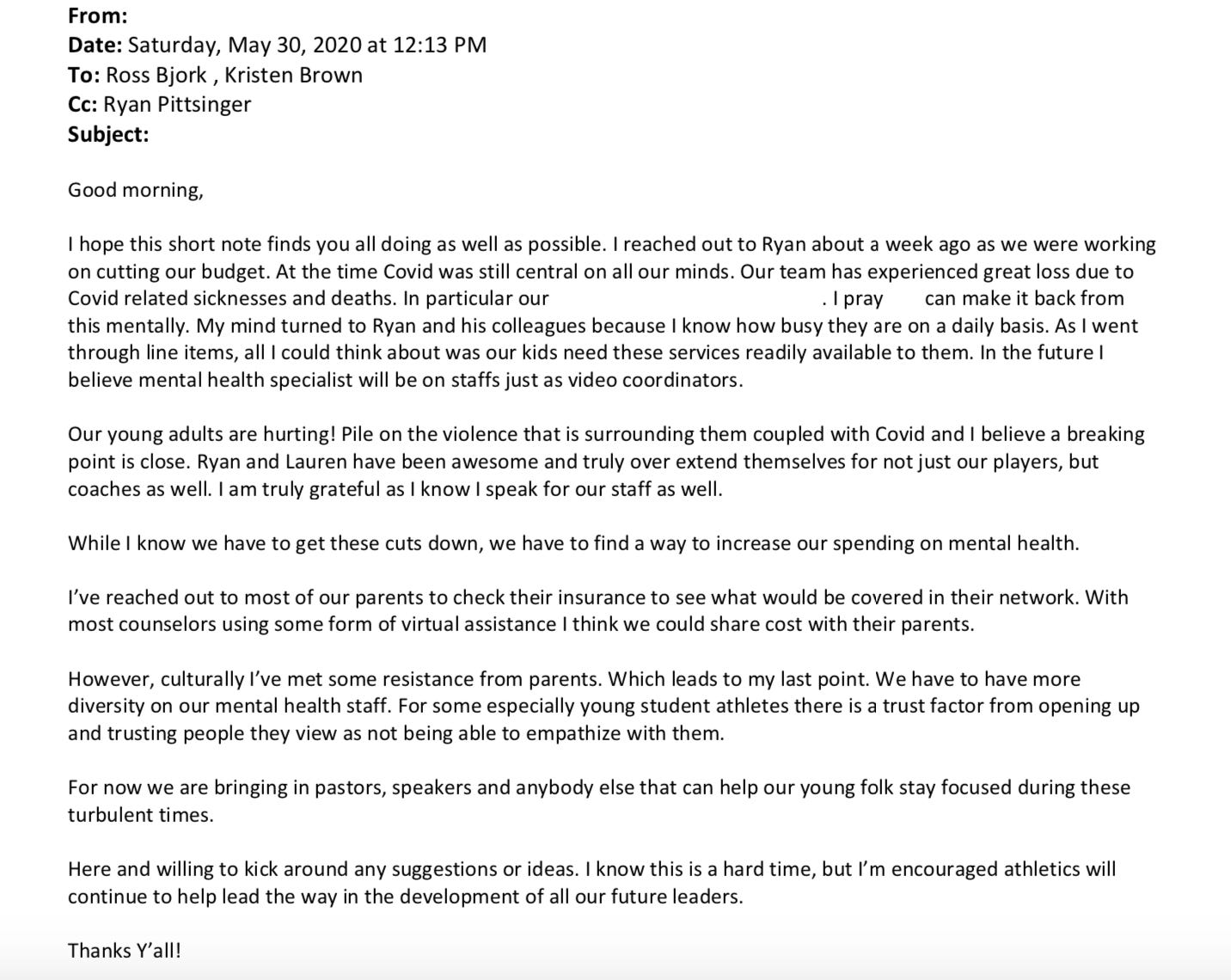

On May 30 – five days after the death of George Floyd and 80 days after college sports shut down – the following email was sent to Texas A&M Athletic Director Ross Bjork and Deputy Athletics Director of Student-Athlete Experience Kristen Brown, while Assistant Athletics Director/Director of Counseling and Sport Psychology Services Dr. Ryan Pittsinger was CC’d.

The sender, the subject line and a few lines of the email were redacted, but the parts that remain detail an impassioned plea from someone who sounds like he or she is on staff of one of the Aggies’ athletic teams.

“While I know we have to get these cuts down,” the sender wrote, “we have to find a way to increase our spending on mental health.”

Here’s the full email (if you’re reading on mobile, click the image to view it in a new window):

Here are a few lines that stood out from the email:

“Our team has experienced great loss due to Covid related sicknesses and deaths. In particular our [redacted]. I pray [redacted] can make it back from this mentally.”

“As I went through line items, all I could think about was our kids need these services readily available to them. In the future I believe mental health specialist [sic] will be on staffs just as video coordinators.”

“Our young adults are hurting! Pile on the violence that is surrounding them coupled with Covid and I believe a breaking point is close.”

“However, culturally I’ve met some resistance from parents.”

“We have to have more diversity on our mental health staff.”

The email raised a number of important concerns and Out of Bounds will explore each of these elements – mental health staff sizes, diversity and racial injustice, and COVID-19 – in this newsletter.

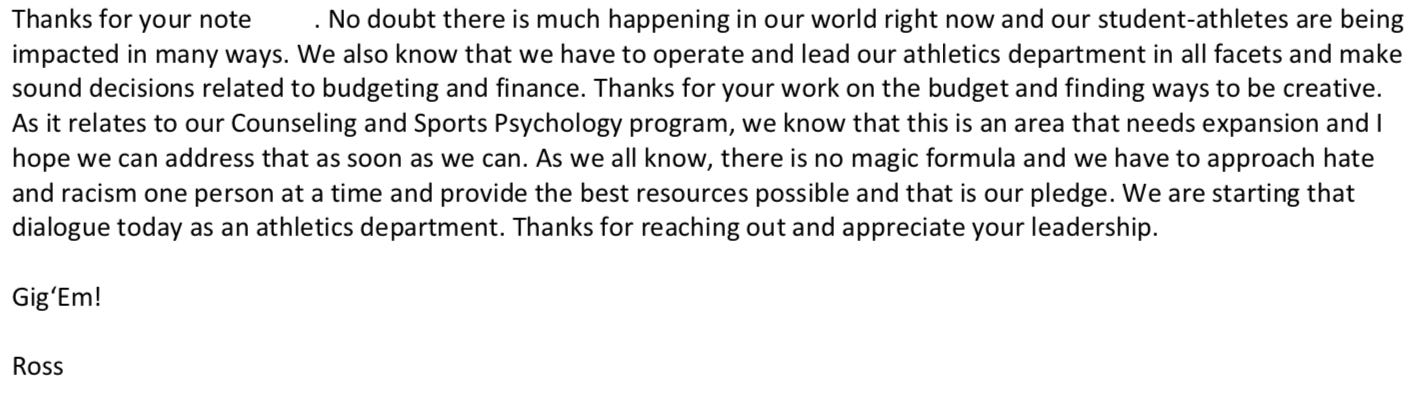

Here’s how Bjork and Pittsinger, respectively, responded to the redacted emailer.

Texas A&M lists two sports psychologists on its athletic department staff directory – Pittsinger and sports psychologist Dr. Lauren Craig, both of whom are white.

“We have to have more diversity on our mental health staff,” wrote the redacted emailer. “For some especially young student athletes there is a trust factor from opening up and trusting people they view as not being able to empathize with them.”

‘They did not meet my needs as a student athlete’

Of course, Texas A&M as a university has a department of Counseling & Psychological Services that falls under its Division of Student Affairs, which Pittsinger referenced in his email response. Roughly a third of those 61 employees in the department are people of color.

You might ask why the size of an athletic department’s mental health support staff matters if the university at large or the university-sponsored health system has a counseling department.

Here’s why.

At the 2019 NCAA Convention, Pac-12-sponsored legislation requiring Power Five schools to make mental health services and resources available through the athletic department or the university’s health or counseling department passed unanimously.

The legislation took effect Aug. 1, 2019.

Previously: ‘You are looking live … at Introductory Accounting here at Kyle Field’

Schools have acknowledged the benefit and/or need for these athletics-specific mental health professionals by hiring them in the first place. Plus, as you read in the Texas A&M email above, and as you’ll continue to read in this newsletter later, athletic department staffers and athletes themselves are specifically asking for more of these services.

In a survey response that’s shown later in this newsletter, one anonymous athlete at Eastern Illinois explained to his or her school that he/she “went to [university] counseling services and they did not meet my needs as a student athlete. I was often encouraged to quit because of my time commitments.”

That kind of advice can undermine the existence and goals of an athlete on campus.

That is why athletic department-specific mental health professionals are important.

Mental health is among the smallest departments within an athletic department

For perspective, here’s how the staff size of Texas A&M Athletics’ two-person Counseling and Sports Psychology Services department stacks up with some other areas of the university’s athletic department, according to its staff directory:

Center for Student-Athlete Services: 24 employees

12th Man Productions: 18 employees

Facilities: 14 employees

Sports Performance: 12 employees

Communications: 11 employees

Texas A&M Ventures: Nine employees

Compliance: Eight employees

Reed Arena: Eight employees

Equipment: Six employees

Marketing: Six employees

Field staff: Five employees

Nutrition: Four employees

Coaches video: Three employees

Anthony Travel: Two employees

Counseling and Sports Psychology Services: Two employees

On its 2019 NCAA Financial Report, Texas A&M’s athletic department reported $43.7 million in profit after earning $212 million in revenue over $169 million in expenses, which included $21.8 million designated to support staff/administrative compensation, benefits and bonuses paid by the university.

Athletic departments have robust academic services departments, as well as departments catered to athlete development and career services, but the average Power Five school has less than two and a half mental health professionals who specifically work with the athletic department, on average, according to an analysis by Out of Bounds.

At some schools, the athletic department’s fundraising organization has more staff members than the total number of mental health specialists employed by entire conferences’ athletic departments. Florida State Athletics’ fundraising arm – Seminole Boosters, Inc. – lists 46 people on its staff directory, and IPTAY at Clemson – an acronym that originally stood for “I pay ten a year” (but the smallest annual donation is actually $60, according to The Greenville News) – lists 25 employees.

A breakdown of the Power Five’s mental health resources

Out of Bounds analyzed every Power Five athletic department’s staff directory and also contacted a media relations representative from every school’s athletic department to give each school the chance to confirm the number of mental health professionals who work specifically with the athletic department, whether they’re athletic department employees, members of their university’s counseling department who are specifically assigned to work with athletes, or outside contractors hired by a school for its athletes.

While every Power Five athlete surely has access to a larger number of mental health resources through the university – remember, it’s official NCAA legislation now – or other mental health services in the community, Out of Bounds focused on the athletic department-specific mental health professionals.

It’s important to note there’s a wide range of job titles in this field and there are differences in those terms, too.

“Unfortunately, that term [“sports psychologist”] gets thrown around a lot and there is a lot of confusion on it so I think it would be useful to provide some direction before just sharing numbers,” wrote one school’s associate athletic director of sports medicine in an email.

Previously: A John Wooden-era college basketball scheduling model to consider for 2020-21

Online Counseling Programs defines sports psychology as an “approach to the mental, behavioral, and emotional well-being of athletes (that) is a combination of applying psychological skills and techniques within the sports industry,” whereas sports counseling “focus(es) more on a holistic approach, taking the mental well-being and emotional needs of the athletes into consideration.” Of course, there could be some overlap, too. Either group of professionals could theoretically help an athlete with his or her relationship with a coach or a teammate, if it’s affecting the athlete on and off the field.

To the best of my ability, here are the number of mental health professionals I was able to confirm work specifically with athletes in each conference, including how many of the professionals are people of color. Unavailable data is noted.

ACC: 29 across 14 institutions (2.07 per school), two people of color

While not listed on Wake Forest’s athletics staff directory, the school “has another therapist and psychiatrist that see our student-athletes in the athletic training room each week,” according to a spokesman. A follow-up request for their names was not answered. A Boston College spokesman responded, “We have access to sports psychologists as part of our partnership with Newton Wellesley hospital.”

In May 2019, the ACC held the first ACC Mental Health and Wellness Summit, and the conference held mental health webinars and videos throughout May.

Big 12: 15 across 10 institutions (1.50 per school), one person of color

Iowa State athletics has a mental health/educational enrichment coordinator, who “coordinates our needs in the area of mental health,” according to a spokesman. “We actually use counselors outside of athletics (campus) and she coordinates and monitors the caseloads.” The mental health/educational enrichment coordinator was included.

Big Ten: 44 across 14 institutions (3.14 per school), eight people of color

Illinois works with The Carle Foundation through the athletic department’s Open Doors program, which offers a psychologist, two psychiatrists and two counselors.

New Big Ten Commissioner Kevin Warren founded the 31-person Big Ten Mental Health and Wellness Cabinet last December, which includes mental health educators, medical doctors, faculty athletic representatives and senior woman administrators.

Pac-12: 27 across 12 institutions (2.25 per school), eight people of color

Dr. Fernando Frias is listed as the Coordinator of Sport Psychology Services on Oregon State Athletics’ website, where he’s the only mental health specialist listed. An Oregon State spokesman responded, “Dr. Frias is part of the OSU Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) program at OSU, but he does work with our athletes as do many other folks at CAPS.” A Washington spokesman replied, “Our athletic department funds two clinical psychologist positions through UW Medicine. The two clinical psychologists are available for direct scheduling for our student-athletes.” Out of Bounds has not learned their names at the time this was written. An Arizona State spokesman responded, “All of our professionals in the medical and mental health fields are provided to us through the ASU Student Health Center on campus.”

There’s a Pac-12 Student-Athlete Health and Well-Being Initiative and an 11-person Mental Health Task Force.

SEC: 40 across 14 institutions (2.86 per school), nine people of color

Former Vanderbilt sports psychologist Vickie Woosley left the school in June. “Our department indeed has a dedicated team to provide these resources to our student-athletes,” a school spokesman wrote in an email. When Out of Bounds followed up to ask if there was an updated staff directory available, the spokesman replied, “Yes, but we are still in the process of finalizing some internal items before posting our new employees.”

A Florida spokesman said, “Our student athletes continue to have access to four licensed mental health counselors.” When Out of Bounds asked for their names, a spokesman replied, “They are not considered full time staff but on retainer and contracted vendors.”

Power Five Total: 155 across 64 institutions (2.42 per school), 28 people of color

Positions such as interns, administrative assistants or film directors/producers weren’t included in the numbers above. The names and racial backgrounds of 10 of the 155 mental health professionals counted above are not known.

To editorialize briefly, I really hope athletes don’t have to work as hard to locate and schedule appointments with mental health professionals as I had to in order to try to pin down a reasonably accurate number for each of the Power Five conferences.

‘Student athletes of color are less likely to find the campus and team environment inclusive and accepting’

The final point made by the redacted Texas A&M athletic department staffer was “We have to have more diversity on our mental health staff.”

To reinforce why it’s so important to have counselors and psychologists from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds within an athletic department, here are the demographics of each Power Five conference’s athletes during the 2018-19 season, using the ethnic designations listed in the NCAA’s Demographics Database:

ACC: 20 percent black, four percent Hispanic/Latino, four percent two or more races, two percent Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

Big 12: 21 percent black, nine percent two or more races, four percent Hispanic/Latino

Big Ten: 14 percent black, five percent two or more races, three percent Hispanic or Latino, two percent Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

Pac-12: 14 percent black, seven percent Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, six percent Hispanic/Latino, six percent two or more races

SEC: 27 percent black, three percent Hispanic/Latino, three percent two or more races

The Big Ten, which had the highest percentage of white athletes among Power Five conferences during the 2018-19 school year, was comprised of 64 percent white athletes. The Pac-12, which was on the other end of the Power Five spectrum, was made up of only 49 percent white athletes, which was still by far the highest of any single ethnicity, but it meant that white athletes made up just less than half of the total athlete population.

Roughly 80 percent of the mental health professionals who work specifically with Power Five athletes, as outlined above, are white. In a world where the racial and ethnic representation among mental health professionals more closely matched the athlete population 1:1, that number would be somewhere between 50 and 65 percent. To re-use a line from the redacted Texas A&M emailer, “For some especially young student athletes there is a trust factor from opening up and trusting people they view as not being able to empathize with them.”

It’s not about questioning the education, certifications or bedside manner of the mental health professionals already in place, but rather about the comfort of an 18 to 22-year-old patient – one who maybe has never seen a counselor or therapist – knowing that they have someone in their athletic department who can relate to their life experiences and upbringing.

To further reinforce this point, Out of Bounds obtained a presentation created by a member of North Carolina’s athletic department in June that’s titled “First Aid Kit for Mental Health.” The notes section below one of the presentation slides reads, “Student athletes of color (especially women) are less likely to find the campus and team environment inclusive and accepting.”

Here’s one slide from the North Carolina presentation that stuck out. First, even while acknowledging that this is a mental health presentation, it seems a little self-serving from an athletic department perspective to associate the return to campus only with positive outcomes and words that have positive connotations, while staying home is presented as having exclusively negative outcomes.

But the words and phrases listed below the arrow to the right should raise tremendous concern for athletes, and the coaches and administrators responsible for them, if more fall athletic seasons are canceled.

In an anonymous end-of-year survey obtained by Out of Bounds, one Bowling Green athlete wrote, “I hope that our administration would understand the importance athletics plays in our daily lives as college students and how much it means to us.”

Some athletes will soon embark on their second consecutive semester of college that’s impacted by COVID-19. If the pandemic isn’t under control when students go home for the semester break, then some athletes could experience a third semester in a row in which the coronavirus shuts down or dramatically affects sports.

What would happen to the mental health of athletes then?

Out of Bounds obtained a “draft thoughts for reaction” memo produced by the Big Ten regarding “Season of Competition Issues” that was written on March 16.

The paragraph regarding winter sports started as follows:

Notwithstanding the emotional pain and unfortunate nature of having a season cancelled as the postseason had begun or was set to begin, under unforeseeable circumstances such as these no less, there is no relief provided in the way of additional eligibility to regain the 2019-20 season. Postseason events are capstones of regular seasons and these championships were for these seasons—they aren’t severable from each other. To give back an entire season that has already been played plus postseason seems like an impulse to try to make things perfect and whole (like going to court to seek replaying part of a game that was impacted by officiating error). Seems inconsistent with the educational component of the realization that life isn’t always fair and some things are more important than sports.

The numbers of mental health professionals listed above show the Big Ten has been a leader in mental health initiatives, especially early in the tenure of new Commissioner Kevin Warren, but as we’re now more than four months removed from when college sports shut down, it’s important that the attitude towards the mental health of athletes who are hurting isn’t the same as the attitude, from the spring, towards their eligibility: “life isn’t always fair” and “some things are more important than sports.”

‘This place took a terrible toll on my mental health for a while’

Some athletes are telling their schools they need more mental health resources, specifically asking for athletic counseling or detailing their personal struggles in end-of-year surveys conducted by universities. Out of Bounds obtained athlete surveys from the 2019-20 school year from several schools via public records requests.

While many schools declined to release their survey results, citing privacy or public records laws, three of the four schools for which Out of Bounds has obtained 2019-20 athlete surveys at the time this newsletter was published have included athletes’ responses that detailed negative mental health experiences related to their respective sports.

These surveys were submitted by athletes to their universities anonymously, and Out of Bounds made redactions in athlete responses where accusations were made against a specific coach, when an athlete’s sport was identifiable in a response in which he/she discussed his/her own mental health struggles or when derogatory terms were used.

These responses are included in this newsletter to show the need for, and importance of, proper mental health resources within athletic departments.

Bowling Green

One Bowling Green athlete wrote that “mental health was not taken all that seriously nor emphatically.”

The final survey report from Bowling Green lists the date June 12, so these responses are a window into how DI athletes were feeling roughly a month and a half ago, well into the pandemic. Twelve of the 157 athletes (7.6%) who responded indicated that they “rarely” or “none of the time” had been feeling relaxed over the previous two weeks. Fifty-six athletes, or 35 percent, said they felt relaxed just “some of the time.”

For each of the following questions, at least seven, and as many as 10, Bowling Green athletes responded that over the previous two weeks, they had “rarely” or “none of the time” been: feeling optimistic about the future; feeling useful; dealing with problems well; or feeling close to other people.

The 21st question of the survey asked, “What can administration do to make your sport program better?”

One athlete responded, “Pay more attention to the individuals in sense of their mental health.” Another wrote, “Improve communication between coaches and [athletes], improve mental health awareness, improve team culture and mentality— bullying has been a problem from the start.”

Eastern Illinois

When asked what additional services he/she would have utilized if available, one senior who played a fall sport at Eastern Illinois last season responded, “Athletic counseling or a sports psychologist of some sort would have been greatly utilized.”

Six of the 25 fall-sport athletes who responded to the school’s survey indicated that they had been subject to coaching techniques or behavior that involved physical, mental or verbal abuse. Here’s what they said when asked to elaborate:

Georgia State

A member of one of Georgia State’s athletic teams wrote that “mental training is not effective” and that members of the team found one coach’s style “offensive, even though those are not [their] intentions.”

A member of Georgia State’s softball team wrote that “Covid-19 has definitely affected the morale of the team and the ability to practice.” The need for adequate mental health resources within athletic departments is magnified when you consider the potential effects of COVID-19 and racial injustice in this country, especially if more sports seasons are canceled this fall.

Those two factors – COVID-19 and race – are very much linked, by the way. The MEAC, which is made up of HBCUs such as Bethune-Cookman, Howard and North Carolina A&T, said as much when the conference announced last week that it was suspending the fall sports season:

The Council of Presidents and Chancellors took this action out of a concern for the safety as well as the physical and mental health of our student-athletes, coaches, administrators, support staff, faculty and fans. The rapid escalation of COVID-19 cases along the eastern seaboard heavily influenced the council’s decision as the data suggests that the African American and other minority communities are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19. The MEAC is committed to ensuring that the correct measures are in place to reduce exposure to the virus.

Out of Bounds asked every Power Five athletic department if they’re actively exploring hiring additional mental health professionals due to the potential effects of COVID-19 and racial injustice.

A handful of schools responded that they’re looking to expand the size of the mental health support staff in their athletic department.

Colorado: “We will be bringing a Post-Doctorate practitioner for this academic year and plan on doing this annually.”

Illinois: “We are looking to add to our number this fall, including adding to the diversity of our staff to help support our black student-athletes.”

N.C. State: “While no one knows the long-term financial implications of COVID, this is viewed as a priority and area of future growth.”

Nebraska: “We are in the process of adding one additional athletic counselor position with the goal of that person starting in mid to late August.”

USC: “Come January, a full-time practicum trainee (to create a pipeline specifically to train sport psychologists of color)...and a part-time sport psychiatrist.”

Washington: “The department will be adding a senior-level Diversity and Inclusion staff position before the end of summer.”

Some schools said they were already working to expand their mental health staff prior to the pandemic. Tennessee is adding an Assistant Director of Mental Health & Wellness and a Northwestern spokesman said, “We are in the process of enhancing the mental health support staff/programming, but that began before the pandemic.”

Some schools can’t add to their staff even if they wanted to. Boston College, Colorado, Oklahoma State, Oregon State and Virginia are among the schools that are in the midst of hiring freezes.

Universities are taking a closer look than ever before at the line-item expenses in their budgets, but athletic departments should probably look long and hard before the mental health resources or other support services for their athletes potentially get left on the cutting room floor in the name of budget cuts. If anything, there’s arguably a greater need for expanded mental health resources for athletes than ever before.

“In the future I believe mental health specialist [sic] will be on staffs just as video coordinators,” wrote the redacted Texas A&M emailer, whose athletic department has six video coordinators compared to two sports pyschologists. “Our young adults are hurting! Pile on the violence that is surrounding them coupled with Covid and I believe a breaking point is close.”

Let’s pray that we don’t find out what that breaking point looks like.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.