A John Wooden-era college basketball scheduling model to consider for 2020-21

Without a bubble environment like the NBA, college teams could limit exposure to COVID-19 by playing two-game series. But first, bigger questions must be asked

Reading time: ~28 minutes

In John Wooden’s first national championship season at UCLA in 1964, the Bruins had played just two conference opponents on the road through mid-February of their undefeated, 30-0 season. Back in ‘64, UCLA played in the Athletic Association of Western Universities (AAWU), along with California, Stanford, USC, Washington and Washington State in a conference that was the successor to the Pacific Coast Conference (PCC) and the precursor to the Pac-8, Pac-10 and Pac-12.

In the six-team conference, which was also referred to as the Big Six by newspapers, there was a 15-game league slate, which meant that every school played the rest of the teams in the conference three times apiece. But rather than, say, UCLA playing at Washington State in January, the Bruins hosting the Cougars in February, and then UCLA going north to play Wazzu in Pullman again in March, the conference schedule-makers just combined the two road games into one road trip.

This was a scheduling philosophy that’s as old as the origins of what is now the Pac-12. Pick a current Pac-12 school, choose one of its men’s basketball seasons from between 60 and 100 years ago, and there’s a good chance its conference schedule looks more like a modern-day college baseball slate than one for a college basketball team.

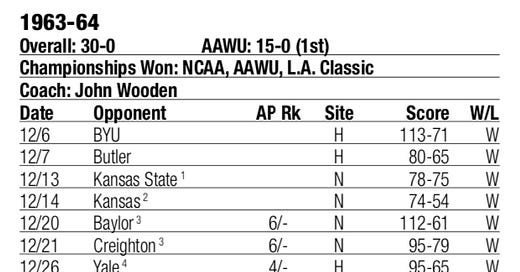

Here’s UCLA’s 1963-64 schedule, courtesy of the school’s media guide.

As we think about what the 2020-21 college basketball season might look like during the COVID-19 pandemic – if there even is a college basketball season, after the Ivy League, Patriot League and MEAC have already canceled or indefinitely suspended fall sports – perhaps there’d be value in conferences considering a one-year shift to a scheduling model similar to the one used by the Pacific Coast Conference and Athletic Association of Western Universities from the 1920s through the mid-1960s, when teams would play the same opponent multiple times on the same road trip.

Previously: ‘You are looking live … at Introductory Accounting here at Kyle Field’

Out of Bounds spoke with an infectious disease expert and a DI men’s basketball conference associate commissioner to discuss the model and other important travel considerations amid the pandemic.

“It’s a neat idea and I’ve seen that before,” said Missouri Valley Conference Associate Commissioner for Institutional Services Greg Walter, who oversees the conference’s regular season schedules. “The potential value from the standpoint of reducing travel for some leagues could be significant.”

Dr. Ron Waldman is a professor of global health and infectious diseases expert at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health. Does he think there could be health benefits from playing just one opponent per week rather than playing multiple teams (potentially in multiple cities) every week?

“Sure,” said Dr. Waldman. “The formula’s not very difficult. Let’s say you have your team with all of its attendant coaches and locker room staff and so on and so forth. So the NBA concept of the bubble can be applied to that team, not entirely, but the idea is just to have a virus-free entity, like a basketball team, where you know there is no virus in that area, within that organization, within that entity. That’s why I brought up the difficulty for collegiates because they have to go to classes and things like that … so if you can take, like, one bubble and move it to another bubble on a different campus once a week. There are risks. It could be doable, the question is how is that team going to get to those other places. Are they going to be on an enclosed bus? Are they going to be on a commercial plane flight?”

Talking with Dr. Waldman, who said he’s an avid sports fan and a Washington Nationals season-ticket holder, is when my own thought process in reporting this newsletter began to shift from “What’s the safest way for there to be a college basketball season?” to “Is there a safe way for there to be a college basketball season?”

“All of this, this whole conversation that we’re having needs to be couched in cautionary terms because frankly we have no idea what the fall and winter is going to bring,” Dr. Waldman said early in our conversation. “Those are usually seasons of higher transmission of respiratory viruses. You’ve heard a lot of talk of second wave and things like that. We don’t know what will happen, even in those countries that have been able to control the spread of the virus much better than the United States has done.”

On Thursday, the NCAA provided its latest update to its Resocialization of Collegiate Sport: Developing Standards for Practice and Competition publication and data shows that the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per one million U.S. residents is nowhere near where April projections expected it to be at this point in the calendar.

The following graph was included in the publication.

"Today, sadly, the data point in the wrong direction,” NCAA President Mark Emmert said Thursday, according to ESPN’s Heather Dinich. “If there is to be college sports in the fall, we need to get a much better handle on the pandemic."

It can be jarring to read, or write, about the competitive concerns about a hypothetical two-game college basketball road trip in one paragraph, which is then followed by another paragraph about the transmission of a deadly virus. “This year, covering sports – if they happen – will require sorting through more cognitive dissonance than ever,” wrote The Ringer’s Bryan Curtis in a piece that was published Wednesday.

Below are some of the pros and cons – which shouldn’t necessarily carry equal weight, by the way, just because each is given a bullet point – of the two-game series model, compared to current men’s basketball conference schedules.

Pros

Limits exposure to just one opponent per week in most, if not all, of conference play; if there’s a positive test for COVID-19 in a conference, it makes contact tracing easier and reduces the number of teams affected by a potential school/conference-mandated quarantine

A reduction in the number of opponents played on the road in conference play from eight to 10 per school (depending on the conference) to four to six

Maintains the same number of total conference games played in each conference and an equal split of home/road games

Some schools will have longer stretches at home in conference play than normal

Financial savings from fewer plane/bus trips

The impact of homecourt advantage could be reduced due to limited seating capacities in arenas, or the complete absence of fans

Cons

Schools would lose most, if not all, home-and-home matchups in conference play in favor of two-game series, where games are either both played at home or both on the road

The home team for a two-game series would have a homecourt advantage for both games in a head-to-head matchup

Some schools will be subject to longer stretches of consecutive road games than they’re used to under their conference’s current scheduling format

Some conferences’ member schools already travel efficiently due to having travel partners or a compact geographical footprint, which means they have less of an incentive to consider a scheduling model like this one

Some arenas are shared by other athletic programs or organizations, which could make it difficult for some schools to schedule two home games in the same weekend

This model could make even more sense if conferences were to announce that they’re limiting their regular-season men’s basketball schedules exclusively to intra-conference play, as the Big Ten and Pac-12 have done for fall sports. Those decisions could allow for more flexibility in scheduling or uniform procedures for COVID-19 testing and reporting, although in regards to the decisions made by the Big Ten and Pac-12, Dr. Waldman said, “I don’t really understand the reasoning behind that.”

Benefits for conferences with larger footprints

Turning a standard one-game road trip into a two-game series could limit the number of road trips in conference play by between 20 and 50 percent, depending on the conference. In recent years, some conferences have expanded their regular-season conference schedules to 20 games (10 home games and 10 road games) and for some schools that fly charter exclusively, 10 road games could mean 10 different road trips.

“The potential value from the standpoint of reducing travel for some leagues could be significant,” said Walter. Walter previously worked for the Summit League, which had an assistant commissioner tell Out of Bounds via email, “The scheduling model you proposed has been discussed by The Summit League membership [in] various sports throughout the years. However, no further action has been taken to look into feasibility (e.g., cost savings, balance schedule, facility conflicts, etc.) of the model.”

While the Pac-12’s predecessors – the PCC and AAWU – were the inspiration for this model, this scheduling format actually wouldn’t provide the same travel or financial benefit in the Pac-12 or other conferences/sports that have weekend travel partners that allow for schools to travel efficiently. In the case of the Pac-12, schools play Arizona/Arizona State, Oregon/Oregon State, Washington/Washington State, etc., in the same week. Walter noted that the Missouri Valley has a similar travel partner arrangement in women’s basketball and volleyball.

The Missouri Valley’s geography works to its benefit for scheduling because its schools are from four neighboring states – Indiana, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri – which means most road trips are by bus. When schools do fly, they primarily take charter flights and their limited commercial air travel can be managed on a one-year basis, according to Walter.

“Men’s basketball for us is a little bit complicated by TV and some of our institutions play in civic arenas that have limited availability so it’d be hard to overlay,” Walter said. “We’ve looked at overlaying those kind of two-games-on-a-weekend model on men’s basketball in the past and it’s always hard to do just given some of the other pieces we have, so for us, like I said at the start, I think we all have our decision trees and there’s a lot of models that could be in place but I’d never say never, at this point.

“I think we’d have to go, for us, a ways down the decision tree to get to that particular model given our geography but I think it’s a reasonable model in the current environment and I could see it being more consideration-worthy in some leagues with larger geographic footprints where the travel on that swing, that sort of middle leg on that trip they’re taking now. If that middle leg is a flight, particularly a commercial flight or even consistently a long bus ride, that’s where it could add some value. That’s where the savings could come, both from exposing people to fewer environments and being on the road less and traveling to fewer places and even just from a cost standpoint. I think that’s where the value would be.”

Commercial flights, by the way, are a non-starter for Dr. Waldman. Out of Bounds asked him what is the safest method of transportation in terms of limiting exposure to the virus, if someone had to travel right now.

“If I was sure there was no virus in my travel group, then I don’t think it matters very much,” he said. “I would say definitely not commercial air so I think those other [forms of transportation] – car caravan, bus, plane – they’re probably equivalent. It’s a physical mechanical separation that we’re talking about that needs to be maintained. It needs to be intact. It needs to be impermeable.”

Most conferences don’t have the luxury, or necessity, of operating with travel partners like Pac-12 does in men’s basketball. Think about the Big Ten, where a school might play at Rutgers on a Wednesday then at Nebraska on a Saturday, or the ACC, where Virginia Tech played at Boston College on a Saturday last season then flew to Miami for a game on Tuesday.

However, the primary benefit of this proposed scheduling model is limiting potential exposure to COVID-19, which would be valuable to any conference.

Playing outside the bubble

Even men’s basketball programs that fly charter exclusively are not living in a secured environment like the NBA’s campus bubble at Walt Disney World, which itself isn’t a perfect system for preventing exposure from the outside world.

But Dr. Waldman was still complimentary of the NBA’s protocols.

“They’re really quite good if they’re followed to the letter,” Dr. Waldman said. “The travel element in college, and by that I mean both on-campus travel back and forth to classes and then travel on an inter-city or inter-state level. Those are all things that the NBA decided they don’t want to do and I think that’s the right decision. I think that kind of travel poses an important level of risk in terms of the virus being able to pierce whatever shield can be put up around the team its accompanying people.”

“…that’s why kind of the NBA decided to bring everybody to one site because they didn’t want to travel but in colleges, I don’t think you can do that. I don’t think the Big Ten can say, ‘OK, bring all your basketball teams to Lansing, Michigan, and we’ll put them in a bubble there, then we’ll play the season’ because they’re supposed to be in college, taking classes and doing other things.

“I think that the bubble concept is very good.”

Anecdotally, having once traveled with the Indiana women’s basketball team on a road trip to Penn State to broadcast the game on radio, I’ve seen firsthand some of the cogs in the machine of a college basketball road trip that can’t be removed or replaced, each of which requires some level of interaction with employees who work in the travel, tourism and hospitality, or service industries. There’s the bus ride from the airport to the hotel (and from the hotel to the arena and back), the hotel employee(s) who check the team in to the hotel and set up a conference room for a pre-game walkthrough and coaches meetings, the elevator rides with other hotel guests to and from the hotel lobby, and the arena worker(s) who let in the visiting team to the arena and locker room.

There are some interactions that are simply unavoidable when traveling, and hopefully social distancing, the wearing of face masks and hand-washing can minimize the risk in those scenarios.

Keep all those small, but not inconsequential, interactions in mind when reading the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s tips for protecting yourself and others:

Outside your home: Put 6 feet of distance between yourself and people who don’t live in your household.

Remember that some people without symptoms may be able to spread virus.

Stay at least 6 feet (about 2 arms’ length) from other people.

Keeping distance from others is especially important for people who are at higher risk of getting very sick.

Out of Bounds polled several high-major programs and they typically travel with 30 to 35 people on the road and if they had to be selective, that number could potentially be cut down to 18 to 20, at a minimum.

The NCAA’s latest resocialization update suggested schools work in small “functional units,” at least during training and physical activity.

Schools should consider the establishment of “functional units” as a strategy to minimize the potential spread of COVID-19. A functional unit may be composed of five to 10 individuals, all members of the same team, who consistently work out and participate in activities together. Assuming that these individuals observe appropriate sanitization, physical distancing and universal masking practices at all other times and do not otherwise place themselves in high contact risk scenarios (for example, attending off-campus social events), the individuals would only be considered high risk to one another.

Interactions at airports and hotels could allow for potential exposure to the virus on the road, just as in-person classes, apartment buildings, restaurants and bars could on campus. Without an NBA-like bubble available for college basketball teams, keeping players, coaches and staff members safe in their respective communities becomes a challenge.

“I assume college athletes would be still going to classes if they’re being offered in a residential way on their campuses,” Dr. Waldman said, “They’ll be engaging in some limited social activities. All of those things represent risk.”

In last week’s edition of Out of Bounds, I shared a statistic from Brazos County, Texas, where Texas A&M is located, that roughly 36 percent of COVID-19 cases were from people in their 20s. Citing that statistic, I asked Dr. Waldman how important buy-in from twenty-somethings is to larger efforts to stop the spread of COVID-19 in the country.

“It’s critical,” he said. “It’s essential for any of this to happen. I’m not starting with a point of departure that there is going to be college athletics.”

The NCAA’s latest Resocialization of Collegiate Sport publication reads, in part:

Student-athletes are students first and, although they may be under relatively strict supervision during their daily commitments to athletics, it is likely that little supervision exists during their remaining hours (for example, in the dorms, at the dining facilities, at parties). For this reason, campus policies coupled with a commitment from each student-athlete to practice infection control are integral to the successful mitigation of the risk of COVID-19 spread within and outside of the athletics department. Without the broader campus policies and practices to guide their behavior when away from athletics, student-athletes may incur more risk through their everyday activities than they might as a participant in a sport with high contact risk.

If college sports are to happen in the 2020-21 school year, modified scheduling models like the one proposed here could help limit exposure to the virus.

Imagine if a conference could cut down from eight to 10 road trips/games per school to four to six. That would be four to six fewer hotels, four to six fewer charter buses or commercial flights, and four to six fewer gameday walkthroughs where a Hyatt employee comes into the conference room to set up your tables and chairs.

Seems worth it, right?

But whatever schedules are utilized next season better be written in pencil, not pen.

“I think for all of us, if we’re fortunate enough to have sports this fall or winter, we’re all going to be operating from a two-part framework,” Walter said, “Like normally we publish a schedule and that’s the schedule and that’s sort of the roadmap. And this year I think we’re all going to have the schedule and we’re all also all going to have decision trees for what happens if you start on time or start late or have an interrupted season or how you build a schedule to try to reduce travel so we’re all trying to build up conversations and try to strike a balance between putting a structure in place and the fact that our landscape changes weekly or even daily. And how do we make sure we operate safely and provide a student-athlete experience that’s positive?”

Here’s how the model would work

To stay with our Pac-12 theme (even though, once again, the conference already has travel partners to reduce travel costs), in the 2020-21 season, UCLA is scheduled to play Arizona, Arizona State, California, Colorado, Oregon, USC, Utah, Washington and Washington State twice. UCLA is supposed to play Oregon State and Stanford just once.

For one season, what if UCLA had a conference schedule where it hosted Oregon, Arizona State, Colorado, Utah and Washington State for two games in Westwood and the Bruins played two road games at Arizona, California, USC and Washington?

“I think in the right circumstance, particularly for leagues that have disparate geography, it’s a reasonable part of a decision tree,” Walter said.

In order to balance the hypothetical 10 home games and eight road games that are outlined above for UCLA, the Bruins might then have to play Oregon State and Stanford once on the road to split their 20-game schedule evenly into 10 home games and 10 road games, assuming that some level of competitive balance is still a priority under this hypothetical model.

That’s four fewer teams the Bruins would have to face on the road in conference play, while they would still play the same number of games against the same teams and still play the same total number of home and road games, albeit in an altered format.

Here’s how conference schedules under this proposed two-game series format could work for high-major conferences, while maintaining the same number of regular-season conference games and an equal number of home/road games:

ACC: Play six conference opponents twice (three two-game series at home, three on the road), play the other eight conference opponents once (four at home, four on the road) – A reduction of three road trips per school; six weeks with just one opponent, four weeks with two opponents

Big 12: Play eight conference opponents twice (four two-game series at home, four on the road), play the other conference opponent (ideally chosen based on geographical proximity) twice in a home-and-home format – A reduction of five road trips per school; nine weeks with just one opponent

Big East: Play 10 conference opponents twice (five two-games series at home, five on the road) – A reduction of five road trips per school; 10 weeks with just one opponent

Big Ten: Play seven conference opponents twice (three/four two-game series at home, three/four on the road), play the other six conference opponents once (if you’re a school that hosts four two-game series, then you’ll have four single-plays on the road and two at home; if you’re a school that hosts three two-game series, then you’ll have four single-plays at home and two on the road) – A reduction of three/four road trips per school; seven weeks with just one opponent, three weeks with two opponents

Pac-12: Play nine conference opponents twice (four/five two-games series at home, four/five on the road), play the other two conference opponents once (if you’re a school that hosts five two-game series, then you’ll have two single-plays on the road; if you’re a school that hosts four two-games series, then you’ll have two single-plays at home) – A reduction of four/five opponents played on the road per school; nine weeks with just one opponent, one week with two opponents

SEC: Play five conference opponents twice (two/three two-game series at home, two/three on the road), play the other eight conference opponents once (if you’re a school that hosts three two-game series, then you’ll have five single-plays on the road and three at home; if you’re a school that hosts two two-game series, then you’ll have five single-plays at home and three on the road) – A reduction of two/three road trips per school; five weeks with just one opponent, four weeks with two opponents

“Interesting concept though – certainly during these times,” the assistant commissioner of one conference replied in an email to Out of Bounds.

Limiting exposure to one school per week

Assuming a 10-week conference schedule from January to March (ignoring one or two conference games that some conferences have scheduled in December), schools would often only be exposed to one opposing team per week during conference play in this model. Under current scheduling models, a school will often be exposed to three opposing teams per week – the first opponent of the week, the second opponent of the week and then through the transitive property, the second opponent’s first opponent from the week.

In weeks where a team has three games scheduled, maybe on a Sunday, Wednesday and Saturday, the number of teams a school is exposed to – either directly or indirectly through an opponent’s direct contact – increases exponentially.

Unfortunately, we need to think about the potential spread of the virus in the same way the Ratings Power Index, or RPI, was calculated. The RPI was previously used by the NCAA men’s basketball selection committee to evaluate teams based on their record and schedule, and it took into account a team’s winning percentage, a team’s opponents’ winning percentage, and its opponents’ opponents’ winning percentage.

Similarly, if a player tests positive for COVID-19 during the season, a conference needs to consider not only the player’s team, but also the team’s opponents and the opponents’ opponents, all of whom could have potentially been exposed to the virus, depending on how quickly a positive case is detected and especially if the person who tested positive is asymptomatic.

Just look at how quickly professional sports franchises across multiple sports were potentially impacted by Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert’s positive test in March.

Imagine the difficulty of contact tracing, and the potential scope of a conference-wide quarantine, if a player from School A tests positive for COVID-19 the week after School A played School B on Sunday, School C on Wednesday and School D on Saturday, with School C having played School E on Sunday and School F on Saturday, and School D having played School G on Sunday and School H on Wednesday. That could be half, if not the majority, of a conference that could potentially be affected by one positive test following a week’s worth of games under a normal conference scheduling model.

That’s why playing just one team, twice per week – assuming every active player, coach, trainer and official has tested negative for the virus prior to competition – could benefit conferences across the country.

When asked if he thinks there’s a level of testing that could allow for safe competition if those who test positive are withheld from competition, Dr. Waldman said, “I think so. As long as there’s an understanding that tests aren’t perfect and that there might be slip-ups or setbacks occasionally. You’re familiar with the NBA concept of how they want to open? There’s the bubble concept but they’re also doing regular testing and I think that could work.”

According to the NCAA’s latest Resocialization of Collegiate Sport update, “For high contact risk sports that are in-season (preseason, regular season, postseason), weekly surveillance testing should be performed for student-athletes, plus ‘inner bubble’ personnel for whom physical distancing, masking and other protective features are not maintained.”

If regular testing is the starting point to the discussion about holding the 2020-21 college basketball season, what is the end point?

What would cause a school, a conference or a larger governing body to punch the “break glass in case of emergency” button?

“I think you can put together protocols and rules that are sensible if you wanted to implement them,” Dr. Waldman said. “As we’re saying, I’m not sure that that’s a great idea, but I think you could do that in a way that lowers the risk, but what I have never seen in anyone’s protocol, and that includes universities in general who are planning on possibly reopening, I’ve never seen what the end point is.

“Once you get started, what would it take to stop? What do you need to say, ‘Well, we can’t do this anymore’? Does somebody have to die? Does somebody’s grandmother have to die? Does there need to be hospitalizations? Just a few positive tests?

“I think that really needs to be specified and thought about seriously beforehand as well because once the train gets out of the station, then gets a little bit hard to stop until it’s too late.”

The final section of the NCAA’s Resocialization of Collegiate Sport is titled “Considerations Related to the Discontinuation of Athletics”:

At the time of this writing, the rate of spread of COVID-19 has been increasing in many regions of the country. Because of this increase, it is possible that sports, especially high contact risk sports, may not be practiced safely in some areas. In conjunction with public health officials, schools should consider pausing or discontinuing athletics activities when local circumstances warrant such consideration.

Maintaining competitive balance

While concerns about competitive balance in this hypothetical format would be far secondary to the safety and wellbeing of players, coaches, trainers and, if allowed in arenas, fans, there are enough advanced stats and rankings systems out there, whether it’s the NCAA’s official NET metric, kenpom.com, KPI, etc., plus smart people in conference offices who could more or less balance all of a school’s two-game home and road series. For every two-game series on the road against a top-25-caliber program, ideally you’d host another top-25-caliber program for two games at home.

“You’d have to get over a pretty significant hurdle in terms of the competitive pieces of that to feel like you were really gaining a lot back in terms of safety and just the travel cost piece of it – the two things you cited,” Walter said. “You know, I think those are the right considerations but I think you’d have to believe that you were generating a lot of savings and a lot of safety benefit.”

This model would undoubtedly leave some schools with longer stretches of road games than they’re used to playing. (On the other hand, it might also give some schools longer stretches of home games than normal and if staying home is the best way to prevent the spread of the virus, then there’s some value there, too.)

While two consecutive weeks’ worth of road games could be a concern for a variety of reasons – primarily, health and safety, but also the educational component since there’ll be reduced in-person classes on many campuses this fall – there are already some DI programs that already play long stretches of home/road games during conference play. Just look below at UT Arlington’s Sun Belt schedule last season: four games in a row on the road, then three at home, then three on the road, then two at home, then two on the road, then five at home, and one on the road.

The Ivy League, Ohio Valley Conference and SWAC have some similar stretches of longer road trips and homestands in conference play, to varying degrees. There are already schools that occasionally go more than two weeks in between home games in conference play.

“Our men’s basketball schedule doesn’t include runs of three or more away games, pretty much period,” Walter said. “And other leagues are similarly structured and so that’s a pretty big change in terms of how that works. That’s not to say if you get down the decision tree far enough or your travel – for those that are doing travel swings in certain sports – that it might not overcome that.”

Other than conferences with a true round-robin league schedule – where every school plays the rest of the teams in the conference once at home and once on the road – many regular season titles are already won by the schools that get to play a lot of the bad and middling teams twice and fellow conference contenders just once. Remember, somebody in the Big Ten gets to play Nebraska and Northwestern twice and Michigan State just once, while another team might have to play Michigan State, Ohio State and Maryland twice apiece.

Life – and unbalanced college basketball conference scheduling – is not always fair.

I also pitched this hypothetical scheduling model in an email to Ken Pomeroy, the mastermind behind kenpom.com.

Here’s what he had to say:

Some scheduling creativity along these lines would be helpful. I think people are in denial about how many cancellations there will be and programs are going to be looking to find games with other healthy teams based on opportunity, whether they are conference games or not.

Competitive balance wouldn't be a problem in itself but the current way of selecting a tournament field completely breaks in this paradigm.

Pomeroy also said it would help if teams weren’t incentivized to maximize the number of games they play in order to improve their resumes.

Limited arena capacities limit homecourt advantage

The other critical component that unfortunately helps the theoretical case for the PCC/AAWU’s conference scheduling model being adopted for the 2020-21 season is that arenas will likely have significantly reduced seating capacities – if they’re allowed to have any fans at all.

“This should’ve been said probably from the outset,” Dr. Waldman said, “but we’re assuming that the student body’s not going to be in the stadiums or the arenas when games are being played.”

An arena that’s at even 15, 20 or 30-percent capacity – let alone empty, other than essential personnel for a game – wouldn’t provide nearly the same homecourt advantage that a big or boisterous place like Rupp Arena, Assembly Hall, Bud Walton Arena or The Pit would be in front of a sellout crowd.

“If most of your membership had buildings in which you aren’t going to have fans, reducing the competitive piece of it,” Walter said, “then some of the homecourt elements and the competitive pieces – like the value of that part of the calculation changes a little bit and so that might make that model more reasonable.”

With no fans at all, games would probably look and feel a lot like those “secret” scrimmages that take place every October, except there’d be a couple of ESPN or CBS or BTN cameras rolling.

“I would consider intercollegiate athletics from the public health perspective to be really a luxury item,” Dr. Waldman said.

But if the show is to go on, it should be done as safely as possible. If the two-game conference series model was accepted for nearly five decades in the early-to-mid-1900s, by schools that now form a high-major conference, when arenas were at full capacity and when the greatest dynasty in the history of the sport (UCLA) was in full swing, then it shouldn’t be unreasonable to consider a similar scheduling model amid a worldwide pandemic and after a months-long drought from meaningful basketball.

But putting concerns about homecourt advantage or balanced scheduling ahead of public safety would really be missing the forest through the trees.

“It’s really putting this in the context of the larger picture,” Dr. Waldman said, “and even if there’s an element of what you asked, ‘Could it be possible that this could happen?’ And I’m saying that there are probably ways to lessen and maybe even minimize the risk, but that doesn’t get around the larger societal question as to should it happen if the situation then is the same as it is now, or a bit worse?”

The greatest homecourt advantage in 2020 is the one we get inside our homes, that limits our exposure to the virus. If enough of us do that for the next six weeks and beyond, then maybe we’ll be able to discuss with more clarity and certainty the 2020-21 college basketball season and that kind of homecourt advantage.

“This country has to get to grips with focusing its attention on the virus and on reducing transmission of the virus,” Dr. Waldman said. “When that happens, everything else can move forward. The economy can move forward, schools can move forward, athletics can move forward. And I don’t know why everyone’s attention is not fixed on reducing transmission in the community. That’s the obstacle to allowing all of these other things to go forward.”

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.