A look at what matters most in college athletics, based on athletic directors' bios

At the start of a new year, maybe publicly available biographies can tell us, or remind us, what matters most to an athletic department

In my grandparents’ kitchen, there are four comfortable rolling chairs that seem to be capable of only having three of their four wheels on the carpet at once, with one straggler almost always slipping onto the hardwood, thud, no matter how hard you try to prevent it from happening. When there are more than four people in the house, one of the youngest people there will be sent to the basement to get overflow seating in the form of some Ohio State folding chairs, which are stored past the prehistoric PlayStation 2 and an old copy of Grand Theft Auto that was once viewed as contraband, past the mounted head of a buck, and past the plastic bowling pins that were once used as a form of mutually assured destruction in an escalating game of dodgeball.

In my grandparents’ kitchen, there’s usually a box of donuts or iced cookies, often gifted by a neighbor, as well as plates of hot breakfast and cups of nondescript but get-the-job-done coffee. The rate at which clean dishes in the house are filled with crumbs and sauce is usually greater than the rate at which dirty dishes are cleaned.

In my grandparents’ kitchen, there’s also a door that leads to their back deck and it’s covered in pictures of Gram and Pop-Pop’s five grandchildren. There are school portraits, graduation photos, a picture with Santa, a nervous smile from a hospital bed and photos from the picture days for youth sports teams that had names like the Bulldogs and the Green Dragons. There are pictures of kids who thought they were too short and pictures of haircuts that were too long. There’s every color of photography backdrop imaginable that you could possibly find at a suburban elementary school in the early 2000s.

As of New Year’s Eve, there were 26 pictures of my sister on the door, compared to 20 of me, and 17, 12 and 11 of our three cousins, respectively, thanks an end-of-year update from Pop-Pop. He initially sent us a shaky, one-second video of the kitchen door by mistake – followed by a picture of the door that allowed for better accounting of the photos – because that’s what happens when the number that’s next to the latest iPhone is 12 and the number that’s next to your age is 85.

Because my sister counts the pictures on my grandparents’ kitchen door religiously, and because she always has, we know that she has been in “first” for years and she lets the whole family know it. Her status on the door is kind of like the Kansas men’s basketball team’s now-defunct streak of 14 consecutive Big 12 regular-season titles, as she’s always in first in November when we visit during Thanksgiving and she’s still in first when we gather there for Easter.

It has become a running joke that my grandparents love her the most because she’s on display in their kitchen more than anyone else. A few weeks ago, my sister sent a selfie from the couch to the family group chat, just to make sure her lead was safe, so Pop-Pop printed it out and hastily added it to the door with a couple slabs of Scotch tape. She has a smug, soft smile and she’s holding up a peace sign – the look of someone who knows she’s comfortably in first place – and now her lead is one picture greater than it was before.

Maybe there’s a hint of truth to the kitchen door and what it means about my grandparents’ affection for my sister, or at least there’s some truth to the greater idea behind it, that what you show off the most is what you care about the most.

If you receive enough Christmas cards every December, you’ve probably become pretty good at discerning which child in a family has the most promising professional career or which grandkid the grandparents get to see the most often or which girlfriend Mom just really isn’t a fan of, and you can make those judgments based on the way the Christmas card is written, or … based on the number of photos there are of a given person in relation to everyone else.

So, I thought, as we embark upon a new year, let’s visit the metaphorical homes of Power 5 athletic directors and see what family photos are on their kitchen doors. What do their Christmas cards look like and which of their kids are they telling you that they’re the most proud of, even if they’re not technically saying it?

I analyzed the online biography for every Power 5 athletic director, plus Notre Dame, which totaled more than 87,000 total words across the 65 athletic directors, in order to see which words and phrases were the most common.

When athletic departments and athletic directors talk about their achievements, or about an athletic director’s past accomplishments that allowed him or her to get hired to such a position, what do they talk about? And how can that help contextualize the decisions that were made during a turbulent 2020 and those that will be made during the remainder of the 2021 academic year?

Similar to the country and to the rest of the world, for college athletics, 2020 was a year arguably unlike any other in our lifetimes. Nearly 100 college athletic programs were eliminated by the end of May, according to The Associated Press, and the number surpassed 250 in October, per The New York Times. The elimination of at least 80 Division I athletic programs was announced last year, and somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 percent of them were men’s or women’s tennis programs.

There were layoffs, furloughs and salary reductions for athletic department staffers across the country.

College athletes individually and collectively found their voices, or in many cases, they were finally allowed to use them, and they were able to do so without fear of retribution or punishment.

Amateur college athletes were granted an extra year of eligibility, as well as the ability to opt out of athletics altogether while keeping their scholarships – although there were still schools in the Big 12, Big Ten, Conference USA, Pac-12 and SEC that didn’t have committable opt-out forms as of October – but there weren’t any other significant benefits or protections that were granted for those athletes beyond what was arguably the bare minimum.

A handful of athletic programs played hopscotch, moving from one location to another when local health restrictions either prohibited athletic competition or required state-mandated quarantining upon returning to the state, which would make traveling to play a Mountain West or Pac-12 schedule nearly impossible.

Name, image and likeness rights for college athletes, whether they’re first introduced through state or federal legislation, are on the horizon.

All of these events created the backdrop for college athletics for the last calendar year and this academic year, which is why it’s worth examining what athletic directors put in their biographies.

Note: Alabama’s Greg Byrne doesn’t have a biography on his athletic department profile so instead, I used the school’s press release from when he was hired, excluding the quotes from Byrne and Alabama coaches. Soon-to-be ACC Commissioner Jim Phillips’s athletic director bio at Northwestern was used for the Wildcats and new Georgia AD Josh Brooks’s bio was used for the Bulldogs. The only parts of an athletic director’s bio that were not included were lists of who had previously served as a school’s athletic director, related links to an athletic director’s introductory press conference, Twitter account or podcast, and the University of Washington’s “About” section for the athletic department as a whole.

You’ll never guess which sport appeared the most

The word “football” appeared a total of 416 times, or an average of more than six times per biography among the 65 athletic directors examined. The word “basketball,” which technically applies to two different sports given that there are men’s and women’s basketball teams, appeared the second-most among all sports. Basketball was mentioned 272 times, or roughly four times per biography, on average.

Baseball (128), golf (112), track and field (95), soccer (91), tennis (73), hockey (70), volleyball (67), softball (66), cross country (56), wrestling (55), lacrosse (46), swimming (43), rowing (40), gymnastics (32), fencing (27) and equestrian (six) took a back seat, to varying degrees. Starting with cross country, every sport in the sentence above was mentioned less than once per athletic director biography, on average, with sports like gymnastics, fencing and equestrian appearing roughly once for every two or three or 10 athletic director bios, respectively.

Granted, not every DI school sponsors every DI sport, but you get the point.

The word “Olympic” was present just 22 times. “Olympics” showed up just once.

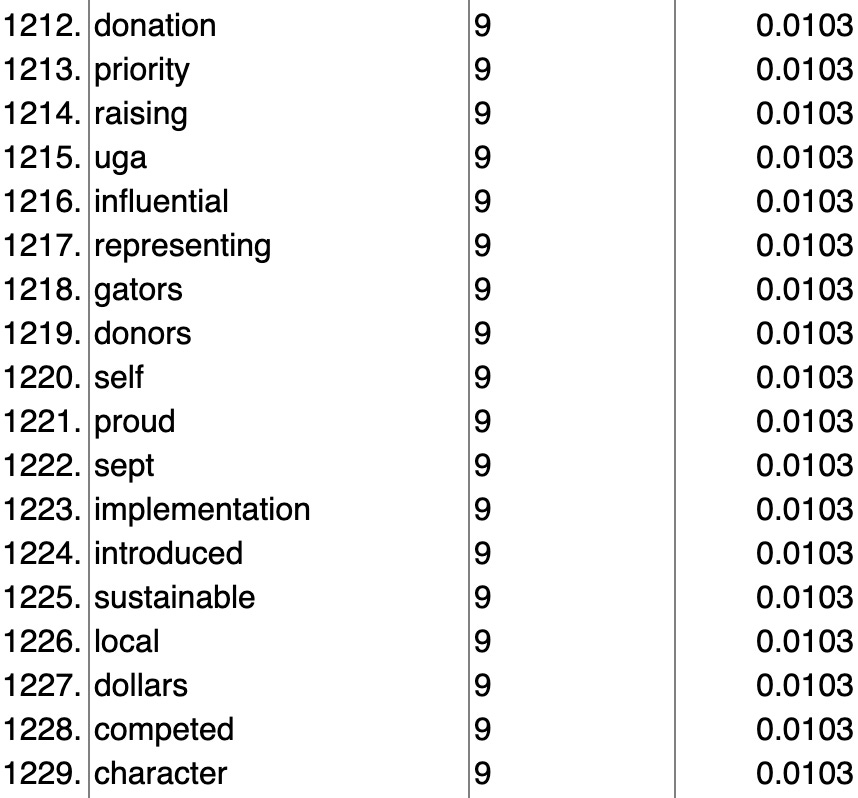

There were, shall we say, some entertaining sentences that you could create, based on the rankings and orders of the most common keywords:

“Sustainable local dollars competed character.”

“Sponsorships moving, broke energy memorial drive launch.”

“Initiatives claimed office budget.”

“Giving saw pandemic earning sales.”

“Recruiting selections streak guided round August contract.”

“Razorback, focused lightweight, already improving.”

“Universities international trips highlights against funds.”

“Donation priority, raising UGA.”

“Gators donors self proud.”

“Wrestler venues drew dedication fundraiser.”

“Louisville upset lives, UConn successes canceled.”

“Elevated resource spending.”

“Almost averages poll respect.”

“Primarily maintaining Boilermakers, deal upgraded.”

“Large investments returning strategy.”

“Money supported chosen surfaces.”

“Bowls, tickets running sugar political capacities.”

“Unparalleled scoreboard landscape.”

“Away recruitment phases collaborative capture.”

“Resurgence planned.”

I swear I didn’t make those up, all of those words showed up in their respective orders.

Money talks

“Fundraising” showed up 86 times, just eight fewer times than “facilities.” “Facility” appeared 115 times. So, if you combine the total results for “facility” and “facilities” and counted those two words as if they were a DI sport, the sport Facilities would rank third among all sports in terms of its usage in athletic director bios, with 63 fewer references than basketball and 81 more than baseball.

“Million” was used 244 times, just nine fewer times than “academic.” “Cash,” “funds” and “fiscal” were each used 11 times, as was “responsibility.”

“Gus Malzahn, Will Muschamp and Tom Herman walk into a golf course’s clubhouse…”

Neither the word “saving” nor “savings” appeared once.

A dollar sign was used 269 times, or just more than four times per AD biography, which was a similar rate at which basketball was mentioned.

“Students” appeared just one more time than “projects” and two more times than “raised.”

But these are amateur student-athletes, and don’t you forget it.

There were 10 results for “mental,” and “psychology” was written in the 65 athletic directors’ biographies just four times, which was as many times as “Heisman,” “Fiesta Bowl,” “remodel,” “sponsors,” “TV” and “quarterback.”

“Health” (28) appeared as many times as “gift.”

Reinforcing how male-dominated the position of athletic director is, “his” (599) and “he” (588) were nearly nine times as prevalent as “her” (67) and “she” (63), the latter of which appeared as many times as “wife.”

The only words used more often than “his” were “the,” “and,” “in,” “of,” “a,” “to,” “for,” “as,” “athletics,” and “at.”

Take out those articles and prepositions, and the conjunction, and the top of the leaderboard of the most frequently used words would read:

Athletics

His

“IX,” as in Title IX, was written just five times.

“Black” showed up just 10 times and “African[-American]” only eight.

“Asian” and “Hispanic” both appeared just once.

The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport recently found that in the fall of 2020, 83.1 percent of the 130 FBS athletic directors are white – an increase of 2.3 percentage points from 2019. Only 12 are women, and only four are women of color.

The institute gave the FBS an “F” gender hiring grade for athletic directors. While the FBS received a B- racial hiring grade for athletic directors, it was noted that the percent of FBS athletic director positions held by people of color was 16.9 percent, which was down 1.6 percentage points from last year.

The most frequently used three-word phrase among the Power 5 athletic directors bios was “director of athletics,” which is typically the wording of an athletic director’s official title. The second-most common three-word phrase was “of the year,” which appeared just one fewer time than “director of athletics,” and 153 mentions of “of the year” translates roughly to 2.2 awards per Power 5 athletic director, or at least awards that were won by the coaches who were hired by those athletic directors.

There were more mentions of “chair of the” (27) than “graduation success rate” (26) or “grade point average” (25).

College athletics loves its committees, its councils and its working groups.

Big Ten athletic directors arguably had some of the longest bios with the last names of Wisconsin’s Barry “Alvarez” (50), Penn State’s Sandy “Barbour” (48) and Illinois’s Josh “Whitman” (37) appearing more often than the total number of times that some of the least-mentioned non-revenue sports appeared across all 65 athletic director bios that were examined. Based on the frequency of those last names, a computer program might wonder who won the national championship in Alvarez, Barbour or Whitman, just as it might in lacrosse (46) or swimming (43).

Not to single out those athletic directors, but it’s revealing when there is likely only one school apiece that would consider writing any of those last names in a biography, compared to just how many ADs that could mention sports like softball or wrestling or swimming when discussing their departments, careers and accomplishments.

But so many Power 5 ADs didn’t, and those who did only did so on a fraction of the scale that football was mentioned.

Media and apparel partners appeared just as often, if not more often, in Power 5 athletic director bios as sports like gymnastics and fencing. There were 43 mentions of “Learfield,” 37 references to “ESPN,” 28 for “Under Armour” and 21 for “IMG.”

Under Armour sponsors several athletic director of the year awards, so chalk up some of the references to the apparel brand to both the importance of awards and corporate sponsors.

“Media” appeared 27 times, just two more times than “rights.” There were 13 references to Nike or Adidas, and 13 to “TV” or “television.”

“Lead1,” an association that represents the FBS athletic directors, was mentioned in the biographies seven times, compared to just two references to “name, image and likeness.”

My thumb is sore from pressing ‘command+F,’ so what does this all mean?

This data isn’t meant to cast athletic directors in a bad light, I promise. It’s meant to cut through their corporate buzzwords, PR speak, honors and awards by, well, analyzing their corporate buzzwords, PR speak, honors and awards. It’s looking at athletic directors’ kitchen doors and Christmas cards in order to try to figure out which child they love the most, or to reaffirm our belief of which child they clearly love the most.

It’s about truth, or at least reality.

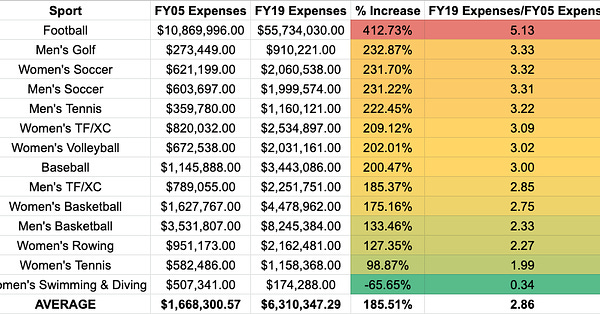

Like it or not, it’s not a surprise to see multiple Power 5 football coaches and their staffs get bought out this coaching cycle for eight-figure sums amid the pandemic, while non-revenue athletic programs have been eliminated with the cause of death listed as “financial reasons” or “the ongoing challenges of the pandemic.”

Sure, the funding for those two things doesn’t always necessarily come from the same place, but there’s also not no correlation between them. Ask yourself why it often seems like it’s easier for a school to find $15 million for a football coach’s buyout than it is for a school to raise the couple million dollars, or less, that it might take to save a wrestling or track and field program.

That is, if the school even wants its wrestling or track and field program to be saved.

However, those anecdotes aren’t a surprise because, on average, you’re going to read about football in an athletic director’s bio almost four times as often as you’ll read about golf, and more than six times as often as softball.

When I wrote about the financial angle of Clemson cutting its men’s track and field program, I came away with the sentiment that if the university was just honest with its alumni base, donors and the members of its track and field program, and if it had said some version of “our football program’s costs are rising more than the costs of any of our other athletic programs and even more so than other top college football programs, and we frankly just care more about our football team being really good than anything else,” it still would’ve stung but that explanation arguably would have sat better with more people.

At least then, if you’re a Clemson track and field athlete, or the parent of one, you’re not being fed a carefully worded statement about financial studies and analyses, or closed-door board meetings where decision-makers supposedly Really Agonized Over The Decision, or whatever.

Because, from athletic director biographies to annual financial reports, the data and information that schools provide to the public tells us that football matters more than almost anything else, so why not just come out and say it?

Now, the fight for Clemson’s track and field program isn’t over and there’s also a very important angle about race in this conversation, as a federal civil rights complaint has been filed against Clemson for racial discrimination due to the impact of the university cutting the program, but strictly from an economic sense, there seemed to be at least some feeling in the track and field community that the pain from losing the program could have been mitigated, at least a little, if the school hadn’t referenced the “the significant financial challenges due to the ongoing pandemic” or “a long period of deliberative discussion and analysis.”

Basically the notion: “Just tell us that football matters more to you and is profitable, and if you don’t let us save the program, then we can move on to schools that actually care about track and field.”

None of this analysis of athletic directors’ biographies should be particularly surprising or revealing, but what it is, is affirming.

I’d encourage you to read a story from The New York Times titled “Was the college football season worth it?” and another from Sports Illustrated called “It took a pandemic to see the distorted state of college sports,” and to go into them with an open mind. Some of the commentary I saw about the two pieces, and much of the premise of the SI story, was centered around the idea that the 2020 college football season “revealed” the true colors of college athletics, but I would balk at that notion.

Instead, the season was the equivalent of producing a page in a “Where’s Waldo?” book where Waldo is dropped, alone, in his light blue jeans and his red, striped shirt and hat, onto the side of a snow-covered mountain that has no distinguishing features and no other people, just snow.

This college football season didn’t reveal anything, it just finally made everything so painfully obvious that you couldn’t miss it or mistake it for anything else.

Even after the pandemic, it’s unlikely that athletic directors’ bios will promote the savings that an AD initiated for his or her university, or how an AD’s department spent money more efficiently, or how the athletic director played hardball with a football coach’s agent to hold off on a potentially premature extension in Year Two, preventing a future $18 million buyout. These are departments that often act like businesses but their universities are labeled as non-profits, so they need to raise and spend more money, improve facilities and win awards – and if they’re fortunate, they’ll maybe even win some games, too – but then at the end of each fiscal year, in most cases, the athletic departments have a balance sheet that shows a small profit, or even a marginal loss.

Whether or not there are the wins or championships to back up any of the fundraising or spending, or facility improvements or coaching buyouts, is almost immaterial. As SI’s Michael Rosenberg wrote in his piece, it’s arguably more important to appear like you’re devoted to winning than it is to actually win:

Successful administrators understand that the most important part of their job—even more than winning football games—is appearing obsessed about winning football games. Customers want to know that whatever the team does, the school expects better.

The pandemic has likely been profitable for those with billable hours – attorneys, public relations firms and consultants – and that has led to stated commitments to diversity and inclusion, shameless uses of the phrase “abundance of caution,” and grave tones about how difficult it was to eliminate [insert non-revenue athletic program here], but if you want the truth – the raw, non-manufactured, unscripted truth – about what those in charge of college athletics really prioritize, then just look at what’s on their kitchen door and that’ll tell you all you need to know.

A quick note

I was honored to be named one of Sportico’s top 50 sports business Twitter follows for 2021 earlier this week. If you’re reading this, I want to thank you, because you played at least a small role in helping make that possible. Without this newsletter and everyone who has read it, subscribed to it or shared it, I’m not on that list.

There have been sports business reporter positions I’ve applied to in the past that ended with me getting ghosted by the company or receiving an automated response email that said some version of “Thanks, but no thanks. You’re not qualified.”

Monday was a good day.

Recap of last week’s newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“If anything, I hope that I’ll take more Taco Bell-like chances with my writing in 2021. Come for the exclusive reporting, hopefully stay for the column on how Purdue implemented a sports wagering policy that didn’t result in a single reported infraction in the first year.

“Even if it’s a little risky or unorthodox, there are probably times where it’s worth taking a swing at a Taco 12-Pack and a 32-ounce Baja Blast at 1 a.m., rather than playing it safe with a beef burrito and a cup of water.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.