Talking taxes: How state income taxes, LLCs and establishing residency could affect NIL income

“I would think the schools in Florida and Texas, for instance, are definitely going to try to use that to their advantage.”

Welcome back to Out of Bounds, a free, weekly newsletter about college athletics. Feedback, tips and story ideas are always welcome at andrew [dot] wittry [at] gmail [dot] com or you can connect with me on Twitter.

One of my worst grades in college was the first exam in BUS-A 100 Basic Accounting Skills, which was followed by a Texas A&M-in-the-2016-NCAA-Tournament-level comeback in the second half of the semester, so I don’t claim to be an expert in accounting or taxes. But I talked to some professionals who are experts in the field, and as someone who filed taxes in three states this year, I can confirm that there are differences from state to state.

College athletes will soon learn this reality, too, if they haven’t already. Some states don’t have state income taxes, while multiple states have a state income tax rate of at least eight percent for their highest respective tax brackets. Some states have a five-figure standard deduction that can be applied to their state income taxes, while others don’t have a standard deduction.

These differing tax policies will soon impact how much name, image and likeness (NIL) revenue college athletes will actually take home, depending on their individual situations. Today’s newsletter is a deep dive into various tax and legal considerations, ranging from state income tax rates, to the benefits of starting an LLC, to whether some athletes should consider establishing residency in a different state in order to save money on taxes.

What you need to know

State income taxes, or the lack thereof, can be a popular talking point for fans and media members who follow or cover professional sports, especially during free agency or around a professional draft, in regard to what percent of athletes’ often multi-million-dollar salaries they’ll owe in taxes.

In most cases, the revenue earned by college athletes will be significantly lower than their professional counterparts but income taxes will obviously be a reality for college athletes, and there will be similarities in how college and professional athletes approach their taxes. The next college athlete to choose a school based upon state income taxes will be the first athlete to do so, but state income taxes could impact how college athletes approach their tax status after they choose a school.

College athletes in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi and New Mexico will be allowed to monetize their NIL rights starting July 1, 2021, which could potentially provide universities and athletes in those states with temporary recruiting and financial advantages, respectively, unless and until Congress or the NCAA passes federal or association-wide legislation, respectively. The NCAA’s goal is to have all of its member institutions abide by the same rules.

That goal is somewhat aspirational, and arguably unachievable, however, in part because of varying state tax laws that will provide athletes who are from, or reside in, select states with financial advantages that can’t be erased or mitigated by NCAA legislation.

There’s a chance that “Come to our school because we’ll help you build your brand and you won’t have to pay any state income taxes on your earnings” could soon be a line that’s uttered to recruits during official visits and in living rooms across the country during in-home recruiting visits, even if it’s a tactic that might sound better than the actual impact it will have on recruiting.

“I would imagine – well, I’m sure – that the schools in Florida and other states that don’t have state income taxes are going to try to use that to their advantage on the recruiting side to pitch to student-athletes, to recruits, and to a certain extent, they probably can achieve some benefit there,” Ken Kurdziel, a CPA and partner at the certified public accounting and consulting firm James Moore & Co., told Out of Bounds, “They probably can have some residency and so forth, especially because, again, if you have a higher dollar amount that they’re earning, then they would no longer be dependents of their parents and they can clearly establish their residency in a state that doesn’t have taxes. So it could amount to something.

“I would think the schools in Florida and Texas, for instance, are definitely going to try to use that to their advantage.”

It remains to be seen how, exactly, granting athletes their NIL rights will affect recruiting, and any speculative claims of the impact of tax-specific recruiting pitches are at risk of being overstated prior to NIL state laws taking effect, but tax rates are unquestionably part of the equation that will determine how much revenue athletes will actually take home from their NIL-related income.

Even if taxes aren’t as sexy of a talking point in larger NIL conversations compared to building a brand on social media or pursuing corporate sponsorships, they’ll be a critical part of college athletes’ future branding and business efforts, especially when it comes to financial planning and reporting.

Let’s start with the basics

Some of the states without a state income tax are among the most talent-rich states in the country, from a recruiting rankings perspective – namely, Florida and Texas – and those states are also home to some of the biggest brands in college athletics, such as the University of Florida, Florida State University, the University of Miami, the University of Texas and Texas A&M University.

Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee (starting this year), Texas, Washington and Wyoming are the states without a state income tax, while New Hampshire only has a five-percent tax on income from dividends and interest.

Other states, such as Delaware, Mississippi or South Carolina, have a graduated income tax rate with no income tax on their respective lowest tax bracket, which would allow for college athletes to not be taxed on small amounts of revenue.

“Obviously every situation is going to be unique,” Kurdziel said, “but in general, I would think the majority of the income sources that these student-athletes are going to have under NIL is going to be as an independent contractor, because they’re not going – in all likelihood – to be employees.

“They could, but they’re probably going to be earning money – a lot of them – from endorsements and advertising and promotional-type activities, and you can imagine the Zion Williamsons of the world will have huge contracts with Nike or Under Armour or some of those [companies] but even a lot of athletes will probably have situations where they start to earn money from maybe a local car dealership.”

There are also standard deductions to consider, which allows specified, smaller amounts of revenue to not be subject to taxes.

“Most of them have some level of standard deduction,” Kurdziel said. “If it’s an athlete who’s only earning a few thousand dollars, there’s a good chance that they’re not actually going to have federal or state income tax because it’ll be covered by the standard deductions.”

Below is a bar chart that shows the maximum standard deduction in each state, listed in order alphabetically, for the 2021 tax year. Most states have a fixed standard deduction, and for some states, the standard deduction in the state matches the federal standard deduction.

(Click on the bar chart below to open an interactive version in a new window)

Even if an athlete’s income is below his or her state’s filing threshold, there could still be a reason to record the transaction, and not just to comply with state laws that pertain to NIL or to-be-determined NCAA legislation.

“‘Are you still required to file in those states, potentially for earned income, just to start that statute of limitations?’ would be the question in these situations,” said Nadia Batey, a CPA and partner at James Moore & Co. who specializes in state and local taxes. “So, if you have a student-athlete who’s below the filing threshold – let’s say in the state of Georgia – but they forgot to tell somebody they received this sponsorship [income], you have to balance it then, ‘OK, we’re under the filing threshold but should we still file to start that statute of limitations?’

“So it’s kind of a risk analysis that you have to go through.”

Comparing the state income tax rates in every state

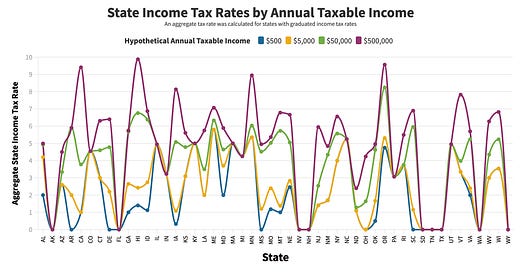

To show the differences in state income tax rates in the U.S., Out of Bounds calculated the income tax rates for four hypothetical annual taxable incomes – $500, $5,000, $50,000 and $500,000 – in all 50 states, plus Washington, D.C., for the 2021 tax year. You can view a complete breakdown of every state’s 2021 income tax rate(s) here, courtesy of Tax Foundation.

This is the amount of income that would theoretically be subject to state income taxes after applying any applicable standard deductions or personal exemptions.

“That’s something we’ve been trying to beat the drum on,” Kurdziel said. “There’s going to be a lot of kids here who all they’re focused on is – understandably so – the ability to earn money off of their name, image and likeness and that’s a good thing, but there are consequences and things compliance-wise they’re going to need to be aware of.”

Note that while some states don’t have a state income tax and others have a fixed state income tax rate, many states have a graduated state income tax, such that the tax rate increases as an individual’s taxable income increases. The higher tax rates only apply to the taxable income that falls within the associated tax bracket. In Mississippi, for example, the first $4,000 of taxable income won’t be taxed during the 2021 tax year, but a three-percent tax rate applies to the next $1,000 of taxable income, a four-percent tax is applied to taxable income from $5,001 to $10,000 in total taxable income, and then there’s a five-percent tax on all taxable income over $10,000.

For states with a graduated income tax rate, Out of Bounds calculated the aggregate percent that an individual would owe in state income taxes for 2021 based upon the applicable tax brackets for each hypothetical amount of taxable income. The state income tax rates don’t include potential local taxes and they assume that an individual is filing a single-filer tax return.

(Click on the line graph below to open an interactive version in a new window, where you can isolate a single annual taxable income by clicking on the legend)

“In California, for example, you’re talking at that high level, you’re talking double digits, so more than 10 percent,” Kurdziel said, as we discussed college athletes who could be among the highest earners from NIL-related income, such as a UCLA gymnast or a USC quarterback. “So comparing that to Florida, it’s a pretty big difference. Now, obviously, L.A. is an incredible media market so they may not care because they may earn plenty to justify the extra 10 to 12 percent of state taxes, but there’s going to be some pretty big differences between states and between localities.”

College athletes could owe taxes in multiple states

“Something that we have to remember too,” Batey said, “is that some of this is going to be sponsorship income and the question then is, even if you have a Florida athlete but they’re playing games in different states and they’re earning sponsorship income maybe by wearing the logos or [doing] commercials or whatever, then is there a responsibility for these athletes to file in multiple states?

“It’s not just your state of college residence. It could potentially open it up to whatever arena you’re playing in, depending on the state rules. That’s the other area that’s going to have to be analyzed and figured out on a state-by-state basis. Then that disparity doesn’t really matter for [whether an athlete is in] Florida or California, it’s kind of like, ‘Well, where did you earn income?’”

“It gets complicated very fast,” Kurdziel added.

Batey brought up the example of a race car that has decals of its sponsors. Some states allocate income earned based on the number of races that take place in the state each year.

“Let’s say AT&T sponsors the company,” Batey said. “You’ve got 30 races over the year but you do two races in North Carolina. Well then North Carolina says, ‘Hey, you’ve got to allocate that [portion of races], two over 30, part of that advertising revenue was earned in our state,’ and so it’s going to be very specific on the state rules and regulations as to how that [income] is allocated. Like Georgia doesn’t have any allocation rules for professional athletes, but there’s still an obligation to report it in Georgia. It’s going to vary. Some of this is going to be based on professional athlete rules that are already out there – entertainers, celebrities, things like that – so we have a base of rules for that type of industry, but it’s applying it now to collegiate athletics.”

Individuals are required to file a tax return in their state of residency, but they could be subject to double taxation if their income is earned in another state. However, many states provide a credit for taxes paid in another state. If an individual’s state of residency has a higher tax rate than the state in which income is earned, then the individual would pay the difference in the tax rate, which is an incentive for athletes to consider establishing residency in a more tax-friendly state.

The benefits of starting an LLC or a corporation

The contracts signed between LSU football coach Ed Orgeron and the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College also featured a third party, My 3 Tiger Boyz LLC. It’s contractually referred to as Orgeron’s company.

LSU Director of Athletics Scott Woodward’s contract with LSU was also signed in part by Woodward’s LLC – Ryan Eric, LLC.

As several NIL state laws will soon take effect July 1, college athletes will want to consider establishing an LLC or a corporation.

“Having an LLC will protect an individual athlete from being personally liable in the event that they get sued,” said Mit Winter, a former college basketball player at William & Mary who now works as an attorney at Kennyhertz Perry. “Let’s say, for example, I think one thing where athletes will be able to take advantage of NIL is holding camps, you know back in their hometown, where they can make a pretty significant amount of money. Let’s say it’s a basketball camp and the athlete doesn’t have an LLC and one of the campers gets injured, the person that they would most likely sue in that situation – if they did end up suing, if it was a bad injury – would be the athlete himself, personally.

“But if the athlete had created an LLC and that’s who was operating the camp instead of the athlete in his individual capacity, the entity would be sued and would be ultimately responsible, so that would protect the athlete and his assets from liability in the event of being sued.”

Winter also mentioned trademark infringement lawsuits as a potential type of lawsuit where it would be beneficial for an athlete to have an LLC, if an athlete has a trademark that he or she is using in connection with an NIL deal. Plus, there are business and tax benefits to establishing an LLC.

“If you have an LLC, it’s going to be a lot easier to keep track of your expenses and revenues because ultimately each athlete is going to basically be a business – for NIL purposes at least,” Winter said. “So you’re going to be able to track your expenses and revenues, which will help you come tax time. It’s going to be easier to then deduct your business expenses, which could lower your tax liability.”

Even though college athletes will enter college at 17, 18 or 19 years old, they’ll have incentives to operate with their long-term financial future in mind.

“There are some potential tax advantages in having everything run through one company,” Batey said, “potentially saving on self-employment tax with creating an S-corporation. One of the things is 18, 19-year-old athletes can start contributing to a self-employed retirement plan, potentially hiring individuals to help them manage this [business], if it’s an agent or family member.

“The one thing I would caution them on is, No. 1, they’re 18, 19-year-old, 20-year-old kids. This is a business and you have to run it as a business. There’s compliance issues of registering an LLC on a yearly basis, making sure that you’re filing your payroll returns or your federal income tax, your state income tax and just making sure that they’re aware that once you go down that LLC, incorporated road, even the self-employed road, is that there’s hoops you have to jump through and we can’t ignore those hoops or they’ll come back and bite you.

“There’s this misconception of, ‘Oh, if I have a business, an LLC, a corporation – I can write off everything.’ Oh, no, we can’t write off everything, but there are certain things you can write off if you run a business and making sure they’re educated on what those are and having them run through that business appropriately.”

Education, representation and tax advice will be critical for athletes.

The house bill passed in the state of Alabama doesn’t “place any obligation on a postsecondary educational institution to provide tax guidance or financial safeguards to student athletes outside of the programming required under this section,” which only requires financial literacy programming for athletes that must cover financial aid, debt management and recommended model budgets. Florida’s senate bill that was signed into law, also effective July 1, similarly requires institutions to conduct a financial literacy and life skills workshop that’s a minimum of five hours at the beginning of both an athlete’s first and third academic years. Those workshops will cover the same topics that are outlined in Alabama’s state law.

Neither the word “tax,” nor “financial,” appears in the state of New Mexico’s Senate Bill 94, which goes into effect at the beginning of July.

Other forms of compensation

One consideration for college athletes who will soon be able to monetize their NIL rights is potential non-cash compensation in deals involving their NILs. As I’ve previously detailed at Stadium, coaching contracts are full of other, non-cash benefits, such as courtesy cars, country club memberships and private flight time.

While receiving a dealer car might sound like an appealing option for a college athlete who doesn’t have a vehicle (and it may also be appealing for a dealership with extra inventory that prefers providing a courtesy car as compensation rather than actual cash), the athlete will still owe taxes on the value of vehicle. That could put an athlete in a precarious position if he or she doesn’t have additional NIL deals that pay the athlete in cash in order to be able to pay the taxes on the car.

“Maybe they’re just given a vehicle as part of doing advertising or promotion,” Kurdziel said. “That’ll be interesting because there you could have a tax issue where you don’t actually have cash associated with it but they get a 1099 from the dealership for the value of the vehicle that they’re providing to them. So that’s potentially a big issue if they’re getting non-cash benefits that have a tax impact on them.”

Batey added, “It’s based on the fair market value of what you receive, so if they receive a car that has a fair market value of $30,000, then they’re going to have to pick up $30,000 of income and there’s a little bit of a disparity there because you get this non-cash asset, but you’ve got to pay for the taxes in cash. So that cash aspect of it has to come from some [other revenue source] or another type of endorsement, sponsorship or whatever it may be. 1099s are issued if you receive any type of value over $600.”

This also applies to goods, clothing and shoes, and the income listed on a 1099 will ultimately need to be picked up as income.

Establishing residency

Last summer, Sportico published a story about Los Angeles Dodgers star Mookie Betts, a Nashville native who reportedly still lives in Tennessee, which is where he could reportedly save roughly $34 million in taxes over the course of his 12-year, $365-million contract extension with the Dodgers (plus the years when he’ll receive deferred payment from the contract), compared to if he established residency in California for the duration of the contract. Obviously a contract worth more than a third of a billion dollars is in a completely different stratosphere than anything college athletes could even dream of earning during a college career that typically maxes out at four or five years, but it doesn’t mean that enterprising college athletes couldn’t try to save money on state income taxes by establishing residency in a state without a state income tax, or at least a state with friendlier income taxes.

Is it possible for college athletes to change which state they establish residency in order to save money on taxes?

“That’s a difficult question in this context because these athletes are students,” said Batey, “and so you have the student rules for the university versus the residency rules [for the state]. Under a normal situation, let’s say that you’re a resident of Alabama and you’ve come to play for the University of Florida. During a student’s educational period – that four years that they’re in the state of Florida – they’re still Alabama residents because they’re usually dependents of their parents and residency rules don’t change just because they’re in Florida for four of those years. They’re still connected to Alabama.

“In this case, then, do you strategically say, ‘OK, at what point do they not become a dependent because of the income that they’re earning and can actually become a resident of a state and fulfill those state residency rules prior to going to the NFL draft?’ Some of that’s going to be strategic planning upon the athlete’s part, or whoever their advisers are, to make sure that they’re abiding by those rules. I’m just wondering if it could mess up anything with their college scholarships, being out-of-state students.

“It’s a lot of moving parts that they’re going to have to figure out, but there’s some strategic planning that could possibly be done to set up residency in that state before their income earned increases by a substantial amount. So I think it’s possible, it’s just that you have those college dependency rules balanced with the state rules on becoming independent or establishing a residency in those states.”

Some states require part-year residents to file their taxes as such, and some states will classify an individual as a full-year resident if the individual spends at least 183 days in the state – more than half of the year. It helps if the individual takes additional measures, such as obtaining a driver’s license or registering to vote in the state, or keeping a log of the number of days in which they’ve resided in the state in a given year.

Even if this discussion is admittedly more likely to be hypothetical than practical for many college athletes, it’s also a topic that has the potential to generate enough energy on an SEC message board to power a college town for a month. At first glance, there are several categories of athletes who could have the ability and/or the incentive to try to take advantage of residency rules to save money on state income taxes:

Athletes who are from a state without a state income tax, or who attend a school in one of those states: If an athlete from a state such as Florida, Tennessee or Texas who’s a dependent of one or both of his or her parents, then the athlete is still a resident of his or her home state, which could have clear tax benefits. Or if an out-of-state athlete who attends college in a state without a state income tax earns enough NIL-related income such that he or she is no longer a dependent, then the athlete could establish residency in the state of his or her school because of the tax advantages.

NFL draft-eligible football players: The key to establishing residency in some states is spending at least half the year in the state. If a draft-eligible college football player withdraws from school after the fall semester and relocates to, say, Florida starting in December or January to train for the NFL draft, then there’s roughly four months that the athlete could live in Florida, perhaps allowing him to find two additional months or so to live in Florida during the rest of the year for the purposes of establishing residency. If a football player withdraws from school because he’s that confident that he’ll be an early-round draft pick, then there’s a good chance that he’s also a fairly marketable athlete, too, which means he could have an incentive to try to find ways to save money on taxes from his eventual professional contract and his already active endorsement income.

The top one percent of the top one percent of earners: Call it the Zion Williamson tier if you want. If there is a select group of college athletes each year who earn high six figures or who even manage to crack the $1-million mark in annual income, it could be worth the effort of establishing residency in a state that doesn’t have state income taxes in order to save somewhere between $50,000 to $100,000. The exact amount of savings would depend on the state income tax rates in the states being compared, as well as an athlete’s taxable income. While earning a mid-five figure gross annual revenue might be the dream for many athletes, the biggest college stars could potentially owe that amount in taxes if they live in a state with a high state income tax.

Athletes whose schools are just across the state line from a state that doesn’t have a state income tax: This is my personal favorite of the categories. Let’s be clear, there are only a handful of Division I schools where this could potentially apply and those schools aren’t necessarily ones that have the biggest athletic departments or the athletic programs that you might expect to attract blue-chip recruits or to develop future pros. But let’s say you’re a college athlete and your campus is only 10 or 20 minutes from a state without a state income tax, such as Tennessee or Washington. If you could confirm that your tuition rates or scholarship status wouldn’t be affected, and if you aren’t a dependent of your parents, would you consider renting an apartment in that other state and then making a short, daily commute if it led to your take-home pay from your NIL deals being significantly higher than the cost of any additional expenses that might come from living further from campus?

Thanks to this user-generated map on Google Maps that shows the locations of all 351 institutions that competed at the Division I level at the time the map was created, we can pick out a few universities that maybe, just maybe, could be home to some athletes who want to be creative with their accounting by living across state lines.

Here are DI campuses that are roughly a 30-minute drive, or less, from a neighboring state that doesn’t have a state income tax, listed in ascending order of drive time, courtesy of MapQuest:

University of Idaho: ~two miles/five minutes from Washington

University of Massachusetts, Lowell: ~four miles/nine minutes from New Hampshire

Murray State University: ~8.5 miles/13 minutes from Tennessee

University of Portland: ~7.5 miles/14 minutes from Washington

Portland State University: ~10 miles/14 minutes from Washington

Alabama A&M University: ~14.5 miles/20 minutes from Tennessee

New Mexico State University: ~23 miles/21 minutes from Texas

Appalachian State University: ~18 miles/28 minutes from Tennessee

Western Kentucky University: ~28 miles/29 minutes from Tennessee

“There’s a lot of variables there,” Kurdziel said. “A lot of variables, and it may be easier said than done, but it does point out the fact that all of this is extremely complex and that these student-athletes, especially the ones earning larger dollar amounts are going to have to have pretty high-level representation, not just from an agent standpoint but also tax planning and whatnot.

“It really looks very similar to what professional athletes have to do.”

It’s too bad there isn’t an SEC institution that’s located a stone’s throw from the border of Florida or Texas – two state income-tax-free safe havens. There are already college dorms that were designed with athletes in mind – most notably, the University of Kentucky’s 32-resident Wildcat Coal Lodge, which is for the university’s men’s basketball team and a similar number of regular students – and the fantasy for any frequent message board poster who lives south of the Mason-Dixon line would be for a university to purchase property across state lines in order to help its athletes escape their home state’s income taxes on their NIL revenue – if they could do so without affecting the cost of the athletes’ tuition or the value of their scholarships.

The signing of NIL state bills into laws means college athletes will soon owe taxes on their earnings and just as creative services are a focus among athletic departments to assist with their athletes’ brand-building, there could be some creative approaches to accounting in the future, too.

In case you missed the last newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“Given how outspoken Kliavkoff was about football-related topics, it will be worth tracking what role he takes in the public spotlight and what issues he addresses when he’s there. ‘While the role requires some public speaking at certain sporting events and industry events, the Pac-12 isn’t necessarily desirous of an ongoing ‘spokesperson,’’ according to the position description. ‘Everything has its time and place. The Commissioner and communications team should discern when and how to deploy communications effectively for the collective.’

“In the campaign to improve Pac-12 football, the time and place was Kliavkoff’s introductory press conference.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew [dot] wittry [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter.