Inside the disputed, uninspired and journalistic origins of college mascots

'You know, legends get to be true after a while. It’s OK.'

Welcome back to Out of Bounds, a free, weekly newsletter about college athletics. Feedback, tips and story ideas are always welcome at andrew [dot] wittry [at] gmail [dot] com or you can connect with me on Twitter.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, you can subscribe for free below.

Local man showers in lake before appearing on Finebaum

A quick, shameless plug at the start of this week’s newsletter. I had the opportunity to make my debut on an ESPN television property last Friday as a guest on The Paul Finebaum Show, where I talked about last week’s newsletter about the Rose Bowl. If you’re interested, you can watch a replay here.

It was an exciting end to the week, as last Friday was our third day in a row without power, forcing Local Man to Shower in Lake, Shave in Relative Darkness with Watering Can Full of Lake Water before Appearing on National TV.

My plan for the weekend was to visit some friends out of town who recently got engaged and to find running water – not necessarily in that order – so I had to make a pit stop on the way at a Best Western Plus off the highway, bum the hotel’s Wi-Fi password (a big shoutout to the front desk employee, Saad) and find a professional-looking backdrop in the hotel’s breakfast cafe in order to pull off the guest appearance on Finebaum.

It was a great experience and if nothing else, it made for a good story.

Speaking of good stories, let’s talk about mascots

Next week marks the return of college football with “Week 0” matchups featuring the Bruins and Rainbow Warriors, Thunderbirds and Spartans, and Aggies and Miners. Mascots and college football go hand in hand, and it will be great to have both back.

Yale University’s bulldog mascot, Handsome Dan, is credited as being one of the first mascots in college athletics. I learned this through a series of mascot origin stories I reported last summer and fall for my job with WarnerMedia in the heart of the pandemic, when there weren’t any live college sports to cover.

What do you report on when, for an indefinite period of time, there’s no current competition?

I stripped college athletics to its core and eventually settled on mascots, scrolling through Sports Reference’s list of the 357 schools that competed in Division I basketball last season to look for unique nicknames.

Anteaters? Yup.

Aggies? Pass.

Demon Deacons? You have my attention.

Bulldogs, tigers or wildcats? No thanks, unless there’s something that makes your bulldog or tiger or wildcat different from the other bulldogs and tigers and wildcats.

For each story, I called someone who was in the know at the university, like a librarian or an archivist. Given Yale’s prominence in the conversation about the popularity of mascots in college athletics, I figured that was one bulldog mascot whose origin story was worth pursuing.

“I’m glad you called me, actually,” Judy Schiff, a chief research archivist at the Yale University Library, told me, “because I went back to check the Yale website – the athletic department – and I don’t know what it is but every time I try to point out the error of their ways, they seem to put up a website that has even more errors about Handsome Dan, so I don’t know whether it’s deliberate or someone is joking around or what it is.

“You know, legends get to be true after a while. It’s OK.”

And that’s when I realized that if the origin story behind one of the first-ever mascots in college athletics is disputed – if not simply untrue – then almost any mascot that followed Handsome Dan’s paw prints toward notoriety and popularity might have overcome (or benefited from) similar half-truths or historical re-writes.

Harper walked so Handsome Dan could run

Yale’s own athletic department website credits Handsome Dan as the university’s first mascot, who was reportedly purchased for $5 in 1889 by a crew and football athlete named Andrew Graves, “who, as an undergraduate, had seen the dog sitting in front of a shop and purchased him from a New Haven blacksmith,” according to the school’s website.

By the way, in months after I talked to Schiff, the chief research archivist, the section of Yale’s website that’s dedicated to Handsome Dan had changed yet again. Either it was yet another example of a deliberate or in-jest change to history, as Schiff had suggested, or maybe someone finally listened to Schiff and corrected the site’s past errors.

“I would say with Yale, the best of it, the gist of it, the part with the saga we want to remember, is true,” Schiff said. “It’s just that some of the facts are not what was. There was another bulldog before Handsome Dan, but Handsome Dan is the one who was revered as the first one.

“His name was Harper and it’s a long story…”

As the story goes – or really, as the story about the story goes – Schiff wrote a column for the Yale Alumni Magazine in 2014, which was the 125th anniversary of Yale adopting Handsome Dan I as its mascot. Schiff thought the university should celebrate the milestone.

The Yale Daily News, which has a claim as the country’s oldest student newspaper, dating back to 1878, had recently completed transferring all of its old issues into a digital format. When Schiff searched the digital archives for stories about Handsome Dan I, she found a predecessor: Harper, who was bred by a bulldog fancier.

Not only was Handsome Dan I not “the absolute first” bulldog, according to Schiff, but she also added context to the Disney-like narrative of a football player buying a bulldog from a blacksmith for a handful of dollars and the dog then spawning a hundred-plus-year lineage of mascots who shared his name.

“None of them would’ve been foundling dogs that came from any blacksmith’s shop, unless it was just someone that was imperfect. Maybe it was a bastard bulldog or something,” Schiff said. “But as far as Handsome Dan, he had a pedigree and he was shown in dog shows, too. I don’t know if it’s still displayed the same way – I haven’t been to the bar at the Yale Club in a while – but they always had a sort of framed display of the dog show medals that Handsome Dan had won back in the 1890s.”

So, while drinking pints at the bar, attendees of the Yale Club could’ve reportedly looked up at the medals Handsome Dan I had won, while the outside narrative about the bulldog had been forged by metal, not medals, given Handsome Dan’s reported upbringing by a blacksmith. (By the way, Handsome Dan I was reportedly far from handsome. "In personal appearance, he seemed like a cross between an alligator and a horned frog, and he was called handsome by the metaphysicians under the law of compensation," the Hartford Courant reported after the canine’s death. Schiff also said, “The look of a bulldog was also different. It was more of a pitbull. It was not bred down to that sort of low, squatty, waddly size that it became.”)

“I think, like any other story at Yale, it’s not so much that people lie or change the story,” Schiff said, “it’s that history changes and a lot of things haven’t been invented yet. There really were no traditional mascots or in fact … I tried to trace the history of the use of the word ‘mascot’ a few years back and of course, we didn’t have as many.”

Schiff continued, “It wasn’t until something like 1906 – I really traced this – that I finally found someone in writing about the Yale team call them the ‘Yale Bulldogs’ and you began to sort of see this creep in as more reporters creating it, until about 1912. And it’s only the football team, and Handsome Dan II did not come into creation until 1933 because they had no concept you could have more than one [mascot].”

Why do we even have mascots?

The need for mascots and nicknames and team colors – or really, the need to distinguish my team from your team – arguably came about in the most Ivy League way possible: sailing.

“It really seems to have just happened that it was really in the boats,” Schiff said. “I think for one thing, you see, college flags, college insignia, that didn’t really start until the late 1850s because you couldn’t really tell what boat was winning when Yale and Harvard began their first race in 1859. They kind of said, ‘Well, who’s going to know who won?’ and somebody at Harvard picked up a red bandana and said, ‘We’ll have this red bandana,’ and Yale said, ‘We’ll have a blue bandana.’ And that’s how Harvard, red, and Yale, blue, got started with the colors and all of that.

“Even with that being told, if you go back probably on some English website, you’ll find that they already had that for a long time in the races in England. What they kind of said was they invented it in America, so there’s many conflicting stories for all of these things.”

The need for, and importance of school colors, nicknames, mascots and logos increased as college football became more popular and as student newspapers began popping up around the country.

“I think that one of the issues that, especially from this time period, you have two things kind of coming around,” Tanya Zanish-Belcher, a senior librarian at Wake Forest’s Z. Smith Reynold Library, told me. “Of course football became kind of a school sport in the 1890s, which is the first time that you see references to a mascot, and of course, originally, we were the Tigers.”

Wait, the Wake Forest…Tigers?

“It’s very rare to even find references to that,” she said. “They had a metal detector and someone found one of the original Tiger buttons or pins and it is so incredibly tiny – I can’t even tell you – you can barely even see it. But it is a tiger and I know that’s where they say they got the idea for the ‘Old Gold and Black’ colors. But I think with the creation of student newspapers, especially in the 1910s, it kind of fostered more of an identity.

“I think both of these things in conjunction promoted school identity and so I think that’s why you start seeing a lot of mascots and names coming around because it’s actually trying to differentiate your school from other schools, and now they had a way to do it, whereas before they didn’t.”

Support local journalism because a journalist may have given your alma mater its nickname

While the escapades of Handsome Dan I often made the local newspapers – he once reportedly tore apart a stuffed dog that a fan of rival Harvard had assembled with red cloth and rags, and brought to the 1893 football game between the two schools in order to taunt Handsome Dan – at least a handful of Division I schools received their nickname because of a newspaper.

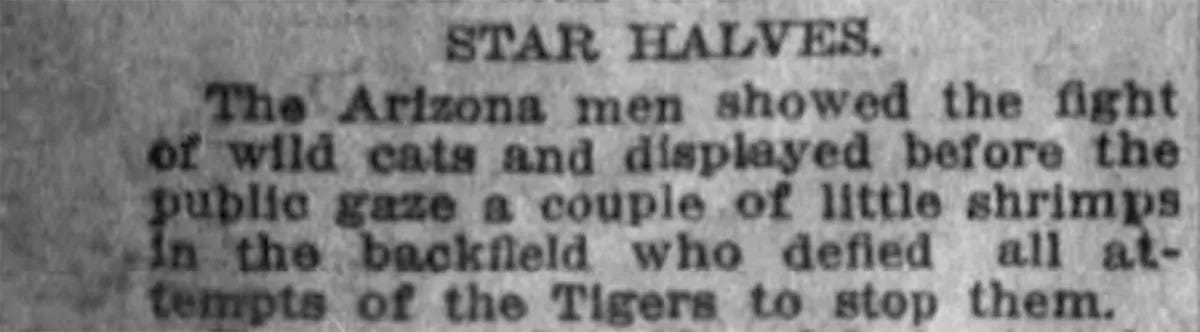

"The Arizona men showed the fight of wild cats and displayed before the public gaze a couple of little shrimps in the backfield who defied all attempts of the Tigers to stop them,” wrote William H. Henry of the Los Angeles Times after the University of Arizona lost to Occidental College 14-0 in football in 1914.

Thus the nickname of Arizona Wildcats was created, albeit after a losing effort.

And that’s how you end up, years later, with some poor pledges pushing a Tucson-area DJ in a wildcat costume in a grocery cart from Tucson to Tempe.

Arizona wasn’t the only school out West to reportedly get its nickname from an L.A. Times reporter who wrote about the team favorably after a defeat.

“All of the media and coverage and write-ups I’ve seen basically say that Owen Bird covered a track meet in early 1912, which USC lost, but he was struck by their fighting spirit so he said they fought like Trojans,” Claude Zachary, a university archivist and manuscripts librarian at USC, told me of the origin story of “Trojans.”

“The common wisdom is that Bird just kind of came up with it on his own.”

How did USC, now with claims to 11 national championships in football, receive praise for being a feisty underdog in defeat? Well, the university technically didn’t have a football team at the time. From 1911 through 1913, it played rugby instead.

"USC stopped playing American football – you know, football – per se, and the football team became a rugby team for two or three years," said Zachary, the archivist and manuscripts librarian, "and then it was only in the mid-1910s that it came back. It was only two or three years. It was really kind of playing around with a lot of that situation.

"We were a small place, really, for the first 30, 40 years. We had a lot of financial ups and downs in the L.A. area. It was a boom-and-bust situation and the university almost closed a couple times and the college itself was really quite small until the end of the teens and early twenties, where things really started to ramp up a lot."

Before being known as the Demon Deacons, Wake Forest – which once again, was once known as the Tigers, so feel free to use that at your favorite local bar’s trivia night sometime – had also been called the Old Gold and Black, Baptists and Deacons. Zanish-Belcher, the senior librarian at Wake Forest, told me she found a story published in 1922 by the student newspaper, which is called the Old Gold and Black, that had a headline that read, “Baptist captain rallies his battling deacons and evens the count in final chapter,” and the story referred to the football team’s center as having played “like a demon veteran.”

“I think they just started putting the word ‘demon’ with it to kind of indicate how tough they were,” she said. "…It makes me think that they haven't exactly put it together yet. I think that at some point, probably, the reporters, the editors started talking. It makes me think that they must’ve just put the two together. They were using the word ‘demon’ and ‘deacon’ and it just came up as something to do, that it seemed like a good combo. Nice alliteration.”

Maybe we’re lucky (most) schools and teams aren’t choosing their mascots today

Imagine what the ballot would look like if a university was trying to pick a nickname through a public vote today. Sure, the Major League Baseball franchise in Cleveland recently announced a name change to “Guardians,” as did Valparaiso University, whose athletic teams will be called the “Beacons” in the future. But those are relatively tame nicknames that have ties to the city of Cleveland and the university, respectively.

Don’t forget that the 2016 U.S. presidential election infamously gave us the independent candidate “Deez Nuts,” who was actually a 15-year-old who had filed as a candidate with the Federal Elections Commission.

The same year, the British government held an online poll to let members of the public vote on the name of a nearly $300-million research ship and the suggestion “Boaty McBoatface” became so popular that the voting website crashed.

In relation to astronomers’ estimated age of the universe (call it nearly 14 billion years, give or take), it was actually a pretty close call (maybe 80-120 years) between the establishment of major college athletics and the adoption of permanent mascots, and the rise of today’s Internet-based, meme culture.

It can be easy to poo-poo common nicknames in sports, such as the Bulldogs and Wildcats, which are the mascots for 15 and 10 NCAA Division I schools, respectively.

“Oh, all you guys could come up with was basically ‘Dogs’ and ‘Cats’? Real original.”

But then again, the Twitter account WeRateDogs now has more than nine million followers. Maybe the only difference between the mascot origin stories from the late 1800s and early 1900s, and the theoretical ones of the 2000s is that if fans of Division I athletic programs were deciding upon their schools’ original mascots and nicknames today, we’d just end up with the Butler Doggos and the Georgia Heckin’ Good Boys 13/10, so maybe nicknames like the Bulldogs and Wildcats aren’t so uninspired after all.

Recap of last week’s newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“The Rose Bowl – and its stated objectives of an independent media contract, ‘a Most Favored Nation position among bowls’ and its requested time slot at 5 p.m. ET on Jan. 1 – could be another hurdle on the way to reaching a consensus on playoff expansion.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.