Here's what team social media policies can tell us about the future of name, image and likeness rights

'There’s a likely scenario where the public will know which student-athletes are earning the most...good luck to the schools that are at the bottom of that list competing in recruiting.'

Team rulebooks for college athletic programs are often filled with bold, underlined and highlighted text, paragraphs that were written in fonts that are often flashier than they are readable, and countless platitudes. “Do The Right Thing” was on the cover of the Iowa State men’s basketball team’s rulebook that was handed out last summer. Some team rules are only a page long, like that of the Louisville women’s volleyball team, while the Texas football coaches’ manual last season was 59 pages.

Through public records requests, Out of Bounds requested the team rulebooks for the 2020-21 academic year for football, men’s and women’s basketball, women’s volleyball and beach volleyball, equestrian and women’s gymnastics programs and obtained copies from more than 50 athletic programs across 16 Power 5 schools.

There’s currently a lot of variance in how individual programs address their expectations and rules for their athletes when it comes to social media. Some programs – Louisville and Nebraska’s women’s basketball programs, for example – don’t specifically mention social media in their team-specific rules, beyond a stated expectation that athletes should be familiar with the athletic department’s athlete handbook.

Other programs give social media a cursory mention.

“What happens within the family, stays within the family!” reads one rule in the Kansas State men’s basketball team’s list of rules. “Be responsible about what you post on social media.”

In the eight pages of policies for Texas A&M equestrian athletes, which starts with a cover page that reads, “The Privilege of Riding for Texas A&M Equestrian,” athletes are only told that “inappropriate social media” is one of 11 examples provided of “strike-worthy offenses,” along with lying, improper grooming of a horse and arriving late to the team bus. The only mention of social media in the Texas Tech football program’s 30-page athlete policy manual is in regards to recruiting and protecting the university from potential NCAA violations. “You may comment on social media about a recruit, provided comments are not made at the direction of an institutional staff member,” the policy manual states.

A handful of programs whose team rules were obtained by Out of Bounds encourage their athletes to post on social media, and a few even provide them with tips, while other programs don’t even have written team rules. Among the schools examined, football programs were the most common sport to not publish team policies, presumably to keep them away from prying eyes. Rutgers football “does not have team rules,” according to an institutional compliance officer for athletics at the university. (Keep that in mind the next time an athlete is suspended for violating team rules.)

Whether they realize it or not, coaches and athletic department administrators are potentially impacting the future earning potential of their school’s athletes based on their current team and athletic department rules, and attitude, regarding social media, and as a byproduct, they’re potentially impacting their school’s ability to recruit athletes in the future.

“There’s this opportunity at hand,” said Sam Weber, the senior director of corporate marketing at the athlete marketing platform Opendorse, “and the colleges who aren’t encouraging and aren’t offering resources and education on how to best build that brand, how to access high-quality content, how to really maximize your value and your time on campus, they’re going to have a harder and harder time recruiting before the rules change. Once the rules do change, a lot of that information is going to be public. There’s a likely scenario where the public will know which student-athletes are earning the most off-field income and which schools’ student-athletes are earning the most opportunities.

“Once that’s out there in the open, good luck to the schools that are at the bottom of that list competing in recruiting.”

Some schools don’t seem to know which social media platforms are popular or how to spell the names of those platforms

It’s hard to pin down exactly how much of name, image and likeness (NIL) monetization will be based around around social media compared to traditional media or other avenues of revenue.

“I don’t [know] right now, no,” Weber said. “You know, it’s honestly going to be fascinating. That’s the assumption right now and I think it’s a safe one that social media monetization, whether it’s active or passive, will make up a significant portion of NIL earning potential for student-athletes, but I think you’ll see a lot of proactive work from student-athletes. You know, putting on skills camps in their hometowns, signing autographs, doing appearances and maybe even you’ll get all the way down – for the bigger-name athletes – like all the way to commercial shoots and longer-term agreements.”

Whether you want to classify social media as the easiest or the most common potential path to monetizing one’s NIL, it’s likely the starting point for many athletes and businesses when the former group is allowed to monetize their names, images and likenesses, which will be funded by the latter’s marketing budgets. When that time comes, schools will want to take a closer look at their social media policies and recommendations for athletes, especially during the recruitment process, when coaches will be asked to explain to athletes, who will be anywhere from 10 to 50 years younger than them, how their school can help an athlete maximize his or her earning potential through social media.

Some team rulebooks unintentionally give off a sort of unironic, Bill Belichick type of vibe when it comes to social media, as in when the New England Patriots head coach famously said in 2017, “As you know, I’m not on SnapFace and all that, so I don’t really get those.”

Rutgers women’s gymnasts are told inappropriate use of social media is prohibited, including on “Snap Chap.”

Maryland’s all-sports handbook for the 2019-20 academic year listed examples of social media websites and networks in its social media guidelines section, and one of the apps listed was Vine, which was shut down by Twitter roughly two and half years earlier in January 2017, when Vine transitioned to the Vine Camera app, which you’ve either never used or you didn’t know existed. Maryland’s handbook listed MySpace, LinkedIn, Flickr and Foursquare before it mentioned Instagram.

The handbook also mentioned “blogs of all types” as a type of social media.

In the latest athlete handbook for UCLA’s women’s volleyball team, the program also included Vine in its definition of social media, even though the app hasn’t existed in the form that once made it popular in more than four years. The handbook also included “any other type of internet blog” in its definition of social media.

Maryland and UCLA both managed to pull off their own versions of that viral Justin Bieber tweet about sports from a few years ago.

“I also don’t know enough about social media to Really have a valid opinion but I do enjoy social media!! And enjoy any high level social media ‘app.’ Any app”

Put yourself in the shoes of an 18 or 19-year-old athlete who has grown up with social media. Would you take social media advice in 2019 from a handbook that mentioned Foursquare and effectively-dead-in-2017 Vine in the same breath as Twitter and Instagram?

Would you be open to social media advice from someone who wrote this?

Applications that allow you to interact with others online require careful consideration to assess the implications of “friending,” “liking,” “following,” “geolocating,” or accepting such a request from another person.

Didn’t think so.

Any social media tips published by an athletic department or an individual athletic program should probably be proofread by an athletic department administrator’s teenager who’s fluent in social media and whose average daily screen time is north of six hours.

By the way, if you’ve enjoyed this “post” make sure to “subscribe” and give a “like” at the bottom of the page!

The Kansas women’s volleyball program might be the gold standard for progressive social media tips

Many college athletes are encouraged to keep their social media accounts private or their social media use to a minimum. Kansas men’s basketball players are told to “keep your setting set on private…,” while the Texas Tech women’s volleyball team rulebook says, “Your social media profiles should be kept as private as possible and not include personal information that can be viewed by the public.” South Carolina’s women’s volleyball players are recommended “having all social media set to ‘private’ and only be for your close friends and family.”

UCLA’s Student-Athlete Code of Conduct states, “Set your account to private. Even if your account is private, your followers can make your postings public.”

The expectation established for Oregon State football players during fall camp last season regarding social media was “less is more.” They were also told, “No jokes or banter about or with teammates.”

While acknowledging there is often a safety component included in social media policies provided by athletic department and team handbooks, such as recommendations that athletes don’t share their contact information on social media, blanket policies for athletes to keep their social media accounts out of the public eye could ultimately hurt the athletes’ future earning potential.

“If you want to call it the ‘old guard’ of teams or athletic departments that are not only not helping their student-athletes build their brands or their audience on social but they’re discouraging it,” Weber said, “I would say those are becoming more and more obsolete, or further and fewer between. In the past few years, that’s started to get pretty rare because student-athletes, they’re on campus with Instagram influencers and kids who are making money off of their YouTube or their Twitch stream, so they’re seeing the value of an engaged, digital audience every day, but until now, until NIL actually comes through, they haven’t had a chance to monetize that the way another student can on campus.

“But regardless, they’re seeing that value and they’re seeing the need or the desire to want to build their brand while they have this captive audience of college sports fans that are naturally fanatics.”

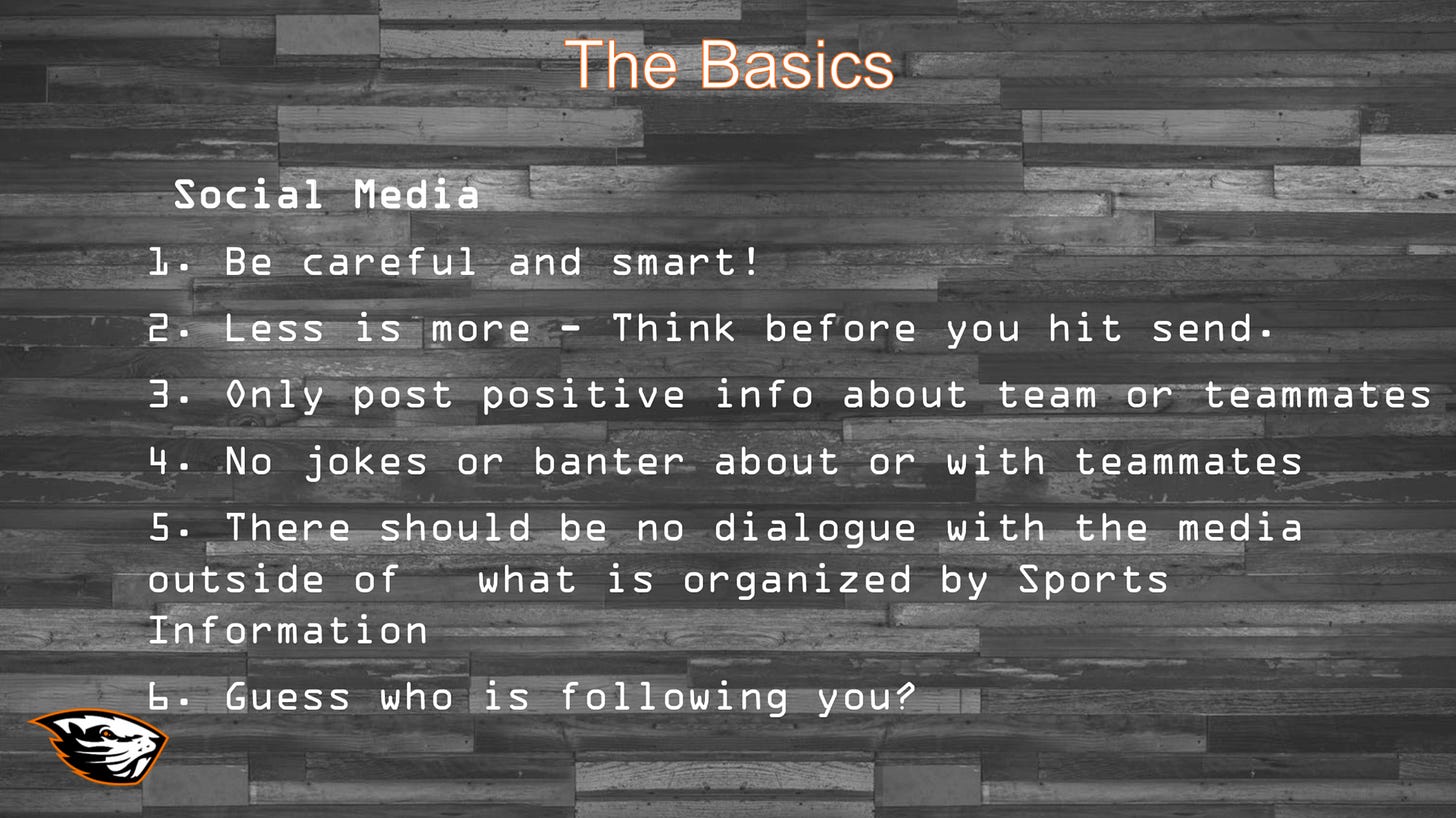

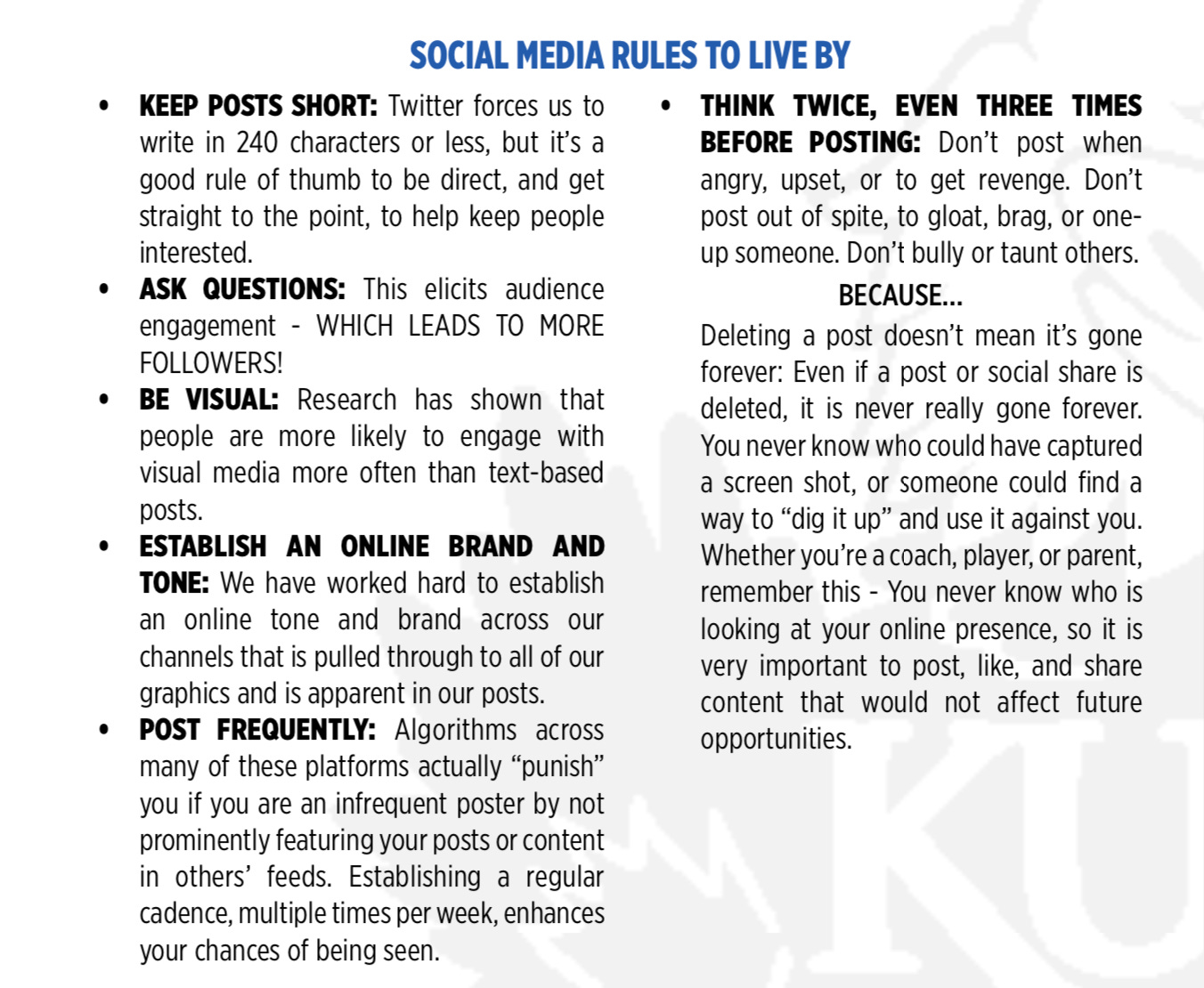

The Kansas women’s volleyball program provides a stark contrast to athletic programs whose policies tell athletes to keep their social media profiles on private, with posts and followers that are limited to friends and family.

“Use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and Snapchat to promote yourself and provide an inside look into the team and University,” Jayhawks women’s volleyball players are told in the program’s two-page guide to working with the media and social media. “Social media provides an inexpensive way to connect with fans, alumni, recruits and other fans all over the world.”

The first page of the guide is devoted to tips such as making eye contact with media members and being complimentary of the team’s opponents, while the second page offers a crash course in brand building. Sure, there are the usual guardrails, such as “If you would not want your coach, parents or future employer to see it, don’t post it!” but the tone and recommendations are just as encouraging as they are cautionary.

One bullet point under “Social Media Rules to Live By” recommends that the team’s players post on social media frequently:

Algorithms across many of these platforms actually “punish” you if you are an infrequent poster by not prominently featuring your posts or content in others’ feeds. Establishing a regular cadence, multiple times per week, enhances your chances of being seen.

Another social media recommendation is to ask questions in social media posts: “This elicits audience engagement – WHICH LEADS TO MORE FOLLOWERS!”

Players are encouraged to be visual in their social media posts, too. “Research has shown that people are more likely to engage with visual media more often than text-based posts,” reads one bullet point.

Kansas Assistant Director of Communications Brent Beerends, whose name was listed as the contact for Kansas women’s volleyball players if they have any questions about social media or digital content, did not respond to an interview request.

The latest team rulebook for the Kentucky women’s basketball program has a page and a half devoted to social media policies. “The best way to engage with our fans and supporters and promote your personal brand is to use social media,” the first bullet point reads. The players are encouraged to use social media and they’re told to download the INFLCR app, which “will help push social media content directly to your phone so you can share with your followers as quickly as possible.”

INFLCR is a platform that allows teams to store and track content, allowing athletes to access content galleries that are personalized for each individual.

Kentucky’s team policies state that INFLCR staff will help provide players with branding and content training, and the program recommends that players “use humor and funny stories” on social media and “above all, BE YOURSELF.”

Arguments against granting athletes their NIL rights have often included talking points about how doing so would hurt women, but among the published team policies examined by Out of Bounds, the athletic programs that give their athletes the most agency and advice in how to build their brands through social media are women’s programs.

In the weeks before California Senate Bill 206, otherwise known as the “Fair Pay to Play Act,” was signed in September 2019, the Pac-12 developed four key messages in its fight against the bill. Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott sent the messaging to California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Chief of Staff Ann O’Leary, as well as Pac-12 presidents, chancellors and athletic directors. The four key messages were later obtained by Out of Bounds. The third key message was titled “Strong Concern for Women’s Sports Under NIL Model” and the first bullet point read, “There is a current fallacy about the benefits of an NIL world to female student-athletes.” The last bullet point of the section stated, “We believe more women student-athletes will be hurt by this bill than helped, which is very concerning for our universities who have been the biggest and best supporters of women’s athletics.”

However, analysis from AthleticDirectorU and Navigate Research found that UCLA gymnast Madison Kocian had an endorsement potential of $466,000 last school year, which was higher than that of Duke men’s basketball player Cassius Stanley and Clemson quarterback Trevor Lawrence. The methodology used to determine earning potential was to place an average endorsement value of $0.80 per Instagram follower.

Ironically, despite the claims from the Pac-12, and others, that NIL rights will cause more harm than benefits for women, seven of the 25 athletes included in the sampling of athletes who were examined by AthleticDirectorU and Navigate Research were women from Pac-12 schools Oregon, UCLA and Washington, across three different sports – basketball, softball and volleyball – but the Pac-12 wants you to know that its universities have been the “biggest and best” supporters of women in college athletics.

In the same study on earning potential, another UCLA gymnast, Kyla Ross, was projected to have an earning potential of $323,000, which was just ahead of Ohio State quarterback Justin Fields ($300,000), who was just ahead of then-Oregon women’s basketball star Sabrina Ionescu ($251,000).

“It’ll be different for every athlete,” Weber said, “but the student-athletes who build an engaged audience right now, they will be the first in line, the easy ones to be able to flip the switch and start making money on day one because they’ll already have that built-in, valuable audience that brands are looking for.”

In a head-to-head comparison of the social media recommendations for Kansas women’s volleyball players versus the Jayhawks’s men’s basketball players, the former set of players is arguably more prepared to maximize their earning potential from their names, images and likenesses through the social media recommendations provided by their program compared to the latter group of players, who are encouraged to keep their social media profiles private.

Some coaches and administrators have acknowledged in writing the social media literacy and acumen of some of their players. Part of the Indiana women’s volleyball team’s rulebook says, “Some of you have exceptional social media skills. Be mindful.” The team manual for the Kentucky’s women’s gymnastics team says, “Social media can be a valuable way to get information out about our team and activities. I encourage you to use it – even during practice, to a certain degree.”

While high school athletes aren’t recruited because of their knowledge of how to maximize online engagement or because of their efficient use of hashtags on Instagram, those are real-world skills in 2021. It’s possible to make a career out of being a social media manager or a brand consultant, so while an athlete posting on Twitter or Instagram may not help his or her team beat Kansas State next Tuesday, it might make the athletes not only more marketable to potential sponsors during their college careers, but also to potential employers.

The programs, like Kansas women’s volleyball and Kentucky women’s basketball, that encourage their athletes to build their brands and to post regularly on social media could have athletes who are better positioned to monetize their NIL once they’re allowed to do so. Athletes who have been told to keep their accounts private and who have potentially been scared into submission from the potential fallout from one digital misstep could face a longer runway in terms of building both the social media following and the skills necessary to maximize their revenue from their NIL.

Keep an eye on the role of sponsored social media posts on game day

The age-old question of “What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?” could become an interesting case study within college locker rooms on game days, once athletes are allowed to monetize their NIL.

Athletes are often told not to post about drugs or alcohol, not to share details about player injuries, and not to criticize opponents, but those are all common-sense policies that shouldn’t impact an athlete’s ability to use or enjoy social media. For many college athletic programs, however, the most restrictive social media policies apply to their cell phone use on game days.

Texas women’s volleyball players are told their cell phones must be turned off when departing for and traveling to matches. They must receive approval from coaches in order to use their cell phones on the team bus. Illinois’s women’s gymnasts are expected to put their phones on airplane mode once warmups start before a meet and they’re told that staff members will handle photography and videography duties. The gymnasts are told that all the pictures from meets will be made available to them later.

Kansas State women’s volleyball players are told, “No phone activity 2 hours prior to matches (with the exception of listening to music) or between games,” as well as “Cell Phones/Head phones are NOT allowed after arriving at practice/competition sites or at team meetings/meals.”

The Kansas women’s volleyball program, which had the forward-looking recommendations about posting frequently and asking questions in social media posts, told its players “no cell phones on during meals” and “no cell phones on during team meetings, practices or matches.”

However, game days might be the most valuable time for athletes to share sponsored posts on social media.

“Athletes have the most attention when the lights are brightest,” Weber said, “and whether that’s when they’re on the court or on the field, or a couple hours before that when fans are getting hyped up for whatever rivalry game it is. There’s a good chance their post that morning would outperform a post any other morning, making it more valuable to that brand or whoever would want to partner with them. The timing and what the restrictions on that will be or could be is interesting.”

Weber said he wouldn’t be surprised if individual athletic programs or conferences adopt policies similar to that of the NFL, which previously imposed a rule that prohibits players from posting on social media starting 90 minutes before games and until they fulfill their postgame obligations to be available to the media, but Weber assumes this will be policed individually within each program.

While it’s not quite an apples-to-apples comparison, many college coaches have incentive structures in their contracts that allow them to receive five and six-figure bonuses by winning rivalry games, conference championships or postseason games, so in the future, coaches could be asked – if not required, if they want to stay competitive in recruiting – to establish cell phone and social media policies that allow their athletes to also maximize their earning potential from their team’s biggest games.

Former Colorado State and Nebraska men’s basketball coach Tim Miles used to have a sports information director tweet halftime thoughts from Miles’s Twitter account during his team’s games, so there has already been at least one high-profile example of mid-game activity on a coach’s social media account. There might have to be concessions on both sides – coaches who allow players to maximize their earning potential with relaxed phone and social media policies, with players also agreeing that certain times in practice and on game days are sacred.

Think about the creative services arms race that has taken place in athletic departments across the country, specifically in regards to college football.

You know, the arms race that led to hype videos like the one below, which was released before LSU played in the 2020 College Football Playoff National Championship and which has been viewed on Twitter more than seven million times.

Schools and individual athletic programs have realized the value of strong, digital content, which often culminates in fast-paced videos featuring quick camera cuts and careful music selection or voiceovers, which are posted on social media in the hours before or after a game. Don’t be surprised if college athletes – at least those with the biggest social media followings and the highest earning potential – (continue to) do the same, especially when there’s a paycheck attached.

Some schools already make player-specific pictures and highlights available for their athletes to post on social media, like the example of the Kentucky women’s basketball program’s use of INFLCR, and depending on how future NIL regulations handle athletes using their school’s trademarks or game footage, you could see athletes post similar hype videos and other game-day content, but the athletes may also simultaneously be promoting a local restaurant, a clothing brand or an energy drink.

That could be the culmination of athletes mastering the finer skills of social media – when to post, which hashtags to use, how to write compelling captions and how to use visuals to tell a story.

“We’ve already seen student-athletes dive in on a deeper level to those type of insights and I think you’ll continue to see that, especially when there are dollar signs attached to it,” Weber said. “Of course, it’ll be natural that the student-athletes that already care about building their brand now, as soon as they’re able to make even more tangible dollars from it, they’re going to spend more time caring about it.”

The Opendorse Ready program, which prepares schools and their athletes for the future of athletes being able to monetize their NIL, provides an in-depth analysis of every athlete’s social media profiles, including their potential annual earning power and how they can make their profiles more effective. The audit can flag previous posts that contain profanity, which can alert athletes to delete those old posts, and it can recommend that an athlete use his or her real name in a social media handle so that fans and brands can more easily locate the athlete.

“I know there are other solutions like that in the market and I welcome it from all parties because I think the more student-athletes understand, the more they realize the opportunity that’s coming for them, whether that’s in college or after they graduate, the better they’re going to be for it,” Weber said. “The better the experience is going to be for fans and the more they’re going to win the second they can begin monetizing that audience.”

Current rules often dictate what a college athlete can or can’t do on social media – who an athlete has to follow, who an athlete has to let follow them or who’s allowed to share the content an athlete posts on social media.

Rutgers women’s volleyball players were told, “You must follow all RUVB social media accounts.” Kansas State women’s volleyball players were instructed, “Do NOT block Coaches & staff views from your social media accounts including ‘Finstas’ and like accounts,” while they are also recommended that “there are tremendous benefits to limiting your time on social media; namely, better time management, better sleep patterns and increased mental health.”

Essentially, “Limit your time on social media but don’t limit your time on social media from us.”

Texas A&M women’s volleyball players were told in their 2020-21 team binder that they “are permitted to have profiles on social networking sites,” as if it’s a privilege, not a right, to sign up for Facebook or Instagram. But they’re also told, “If together or doing a fun team activity, please send [Assistant Director of Athletic Communications] Marissa [Avanzato] photos for her to post on social media,” so while the program is gracious enough to allow its athletes to be on social media, it also wants in on the action if it can use social media to market itself.

“@AggieVolleyball is allowed to retweet your tweets, repost your Insta’s,” reads one bullet point in the team binder.

Kentucky women’s basketball players are told in their team rulebook that representing the university and using social media is a privilege and “will be taken away if the policies and rules (above) are not followed.” Their first offense will lead to the deletion of the offending post and a one-on-one meeting with a staff member about social media, a second offense results in mandatory community service and the loss of social media privileges for a period determined by the coaching staff, and a third offense results in a player losing all social media privileges, plus a potential suspension for a practice or a game.

Soon, college athletes will have more control over their social media profiles, and game days might be the epicenter of both the most potential conflict and the most potential profit. It’s the time when coaches arguably want the most control over their programs and the fewest distractions, but it could also be when players’ earning potential is the greatest.

Recap of the last newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“It is interesting how the men’s teams have gotten a lot more attention than some of the women’s teams that have chosen not to play,” said Dr. Kate Lavelle, who’s an associate professor in Communication Studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and whose research program focuses on the representation of race, gender and nationality in sports. “It’s been kind of a loss of conversation about why they are choosing not to play.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.