Athletic departments forced to navigate hot-button issues tied to fundraising amid decreases in revenue

Revenue and contributions have declined for many athletic departments, and coaching scandals, program cuts and social activism can jeopardize revenue even more

Just eight days before The Athletic broke the news that there was an active investigation into the alleged behavior of now-former Wichita State men’s basketball coach Gregg Marshall – an investigation that was prompted by the months-long reporting from Stadium’s Jeff Goodman – Wichita State invited donors to a ribbon-cutting event at its new Student-Athlete Center in late September.

In preparation for the event, Wichita State filmed videos of various members of the athletic department, specifically coaches and athletes, including Marshall, four track and field or cross country athletes, a softball player and a men’s tennis player, among others, each of whom was asked to describe how the center will be used and its potential benefits, according to emails obtained by Out of Bounds.

“The donors will be taking a tour through the new space, and these videos will be playing in the lobby area as they go throughout their tour,” Wichita State Director of Digital Media & Branding Kayla Knight wrote in an email to athletic department communications staffers on Sept. 14, 2020.

Knight continued:

It will be a sit-down interview with the following type questions:

What will this new space(s) be used for?

How does this new space benefit you/your team? / Recruiting

What does this new space mean to you? Thank / show their appreciation to everyone who has given in order for the programs to continue to be successful, etc. etc.

Attendance at events like this is one of the perks that comes with being a donor, or at least a donor who carries enough weight with the university or one whose checks carry enough zeros. It might mean occasional facetime with some of your alma mater or local school’s head coaches and athletes, and if the checks are big enough or written frequently enough, then maybe your last name can find a home on the outside of a learning center or a training facility.

Just over a month after the ribbon-cutting ceremony and several weeks after the news broke regarding the investigation into Marshall’s alleged behavior, a group of Wichita State supporters who called themselves “Shockers for Coach Marshall” took out a full-page ad in The Wichita Eagle.

“Shockers for Coach Marshall proudly stands with our coach,” part of the advertisement read. “We know his true character. We’ll be rooting for Coach Marshall and the Shocker team for years to come.”

Marshall reportedly punched former Wichita State player Shaq Morris from behind during a practice, between his shoulders and near his neck, multiple former players told The Athletic and Stadium. Marshall allegedly choked a former Wichita State assistant coach. Once, Marshall allegedly saw a Wichita State athlete from another athletic program pulling out of Marshall’s parking spot, so Marshall allegedly followed the student in his car and blocked the car at an intersection, yelling at the student before allegedly attempting to punch the student through the car window.

The ad in The Wichita Eagle listed the names of 180 supporters, including former Wichita State star Xavier McDaniel, whose No. 34 jersey was retired by the university. Online searches show the members of “Shockers for Coach Marshall” include the CEO of a large accounting firm in Wichita, a former president of the alumni association who has an endowed business scholarship that’s in the name of he and his wife, a couple who has an endowed scholarship for dental hygiene, and one man owns a popular restaurant chain in town.

One couple whose names were listed was featured in a Kansas.com profile of Wichita State fans who were in attendance for the school’s loss to Kentucky in the second round of the 2014 NCAA Tournament, which ended Wichita State’s previously undefeated season. The couple had reportedly traveled to every Wichita State game that season – home and away – and the husband told the newspaper that starting in January, he had refused to shave until the Shockers lost. The newspaper provided color of the wife wiping away tears after the loss.

On Nov. 17, Marshall resigned from his position as head coach, 13 days after the ad ran in The Wichita Eagle. He signed a 16-page confidential separation agreement in which he and the university agreed he will receive 156 payments of $48,076.92 – he’ll receive a payment once every two weeks for six years, which will total $7.5 million.

While Marshall is no longer working at university, many of the supporters whose names were in the newspaper ad are likely still around, metaphorically through their donations and support of the university, if not quite literally still around – as in they could be on the guest lists for future ribbon-cutting events and other various fundraisers and banquets. And if they’re not around anymore, then the literal cost to Wichita State of the allegations that were detailed in the reporting by The Athletic and Stadium was even greater than the seven-figure sum that will be paid to Marshall through 2026.

While no men’s basketball players were listed as interview subjects for the videos produced for the ribbon-cutting ceremony, other athletes across multiple sports were asked a list of questions and prompts, including the bullet point that asked the athletes to “thank / show their appreciation to everyone who has given in order for the programs to continue to be successful.”

“The project was funded by private donations through the generosity of Wichita State supporters who contributed to a fundraising campaign led by the WSU Foundation and WSU Athletics,” stated a news release on Wichita State’s website about the opening of the Student-Athlete Center.

What does it say if some of the donors for the Student-Athlete Center, who Wichita State athletes were asked to thank and to show their appreciation, were also members of the group that, just a few weeks later, publicly supported Marshall after he was credibly accused of punching one player, choking an assistant coach, taunting a player of Native American descent and body shaming another player?

Out of Bounds filed a public records request for a copy of the guest list for the university’s ribbon-cutting event at the student center but the university said it didn’t have any responsive documents. The news release on Wichita State’s website for the ribbon-cutting ceremony included a photo gallery of the day’s events and some of its attendees.

In a city of about 390,000, is it possible that the attendees of the ribbon-cutting ceremony (and the other donors who contributed but weren’t present) were mutually exclusive from the 180 names that were in the ad in the The Wichita Eagle? Well, that depends on just how many self-described “longtime supporters” there are in and around south-central Kansas who support the former longtime Missouri Valley Conference school.

In a vacuum, some form of “thank you” to donors who write big checks isn’t inherently a bad thing, but the dynamic becomes uncomfortable when considering the possibility that unpaid, amateur athletes were asked – maybe even told – to show deference to boosters, some of whom potentially offered brazen support of a multi-millionaire coach who was accused of physical and verbal attacks against his players and at least one assistant coach.

As stated in the email above, the donations for the Student-Athlete Center were framed as necessary “in order for the programs to continue to be successful.” Was the clear and public backing of Marshall by a notable segment of Wichita State’s fan base also necessary in allowing his alleged behavior to run rampant for so long?

Within the four-sided relationship between university and athletic department administrators, coaches, athletes and donors in college athletics ecosystems – a network that often involves the exertion of, and imbalances in, money, power and influence – you could argue that the athletes have the least amount of say in that group, especially when considering additional reporting from The Athletic in October:

As Wichita State conducts an internal investigation of its head basketball coach because of allegations of verbal and physical abuse, seven players from Marshall’s time coaching at Winthrop (from 1998 to 2007) painted a picture of Marshall — menacing, belligerent, prone to sudden outbursts — similar to the one former Wichita State players have detailed.

Without the current coverage of the NCAA transfer portal, which featured 10 Wichita State players over the previous two seasons and which has become its own niche market in the media industry, the details of Marshall’s alleged behavior at Wichita State could’ve gone the route of his alleged behavior at Winthrop – unreported and unchecked for decades.

But don’t think these potential alignment issues or questions are unique, or that they only arise during coaching scandals

Many athletic departments saw a significant year-over-year decrease in revenue from the 2019 fiscal year to 2020, and the reported decline in revenue will likely be more severe this fiscal year. That’s where this conversation gets tricky. At what cost, literal or metaphorical, will universities and athletic departments go to stay afloat, or to maintain the lifestyle they’re accustomed to in terms of facilities and coaching contracts?

Schools need to maximize as many sources of revenue as possible, especially after the 2020 NCAA men’s basketball tournament was canceled and when attendance at athletic competitions this school year has been limited or nonexistent. Financial guarantees that are often tied to non-conference games were significantly reduced in men’s basketball and many were lost entirely during the football season.

The early returns from the NCAA Financial Reports for the 2020 fiscal year suggest that Power 5 athletic departments saw their revenue decrease by an average of roughly $9 million from the previous year, with contributions decreasing by an average of at least $5 million. I’ll have more specific numbers soon, but the point is that the 2020 fiscal year wasn’t kind to a lot of athletic department budgets and the 2019-20 numbers don’t even begin to tell the full story on the financial effects that the pandemic has had on college athletics during the 2020-21 fiscal year.

Not only are schools impacted by things that are often outside of their control, such as a global pandemic, local and state health protocols, or decisions made by other athletic conferences, but the decisions made by their own administrators, coaches and players can also impact their bottom line, especially right now.

Schools can potentially jeopardize their revenue from ticket sales and donations by keeping a coach.

Schools can potentially jeopardize their revenue by getting rid of a coach.

Schools can potentially jeopardize their revenue by potentially hiring, or not hiring, a candidate for a head coaching job that never actually opened.

Schools can potentially jeopardize their revenue by getting rid of an entire athletic program.

There’s a host of reasons why boosters could be turned off right now – or why they could be rallied in the face of budget cuts, furloughs, and postponed and canceled games and seasons. Boosters who throw their weight around, especially in college football, have existed since the dawn of the sport, but the pandemic has brought to the forefront even more reasons and even more urgency for schools and donors to try to leverage the latter’s ability to write checks to the former.

After Colorado Athletic Director Rick George sent a mass email to the school’s fans on the day the Pac-12 announced it had postponed all sports for the rest of the calendar year, one Colorado donor, whose name was redacted in an email obtained by Out of Bounds, wrote to George, “I know this is a time of need for the Department so have [Assistant Director of Development for the Buff Club] Casey Gibson call me and we’ll make a donation in the form of sponsoring a few lockers or some other manner.”

While the Pac-12 ultimately reversed course, in the face of a fall without football or any other sports, and without all the associated revenue, even the unprovoked generosity in the form of a few sponsored lockers from an empathetic donor would likely only represent a rounding error and it wouldn’t resemble anything even close to a bailout for a Colorado athletic department that reported $94.9 million in revenue during the 2019 fiscal year.

And for some athletic programs, there may soon no longer be physical lockers, or even a program, to even sponsor.

After Michigan State announced last October it was cutting its men’s and women’s swimming and diving programs, one supporter of the programs sent an email to a number of Michigan State administrators, including President Samuel Stanley, Athletic Director Bill Beekman and the Board of Trustees, with a subject line that read, “Ashamed of MSU for cutting swimming, I will never donate again.”

Another emailer wrote to Stanley, “I donated [redacted] during a pandemic. Now the swim team is gone. I just don’t know what to say.”

Earlier in January, 11 members of the women’s swimming and diving team filed a federal lawsuit to stop the university from eliminating the program, according to ESPN.

After Bowling Green announced its baseball program was going to be eliminated, only for the program to be saved by donors who pledged $1.5 million over three years, one of the individuals who financially supported the program’s lifeline was unhappy to learn last summer that the school wouldn’t be playing fall baseball.

“Just coming off of giving quite a bit of money to help save the program doesn’t make me feel very good that fall intrasquad baseball is canceled,” a man named Jason Kelley wrote in an email to Athletic Director Bob Moosbrugger, among other administrators. “Simply makes no sense.”

Unfortunately, the actions from schools and athletes that take a stand against racism and social injustice can also threaten the contributions that schools receive.

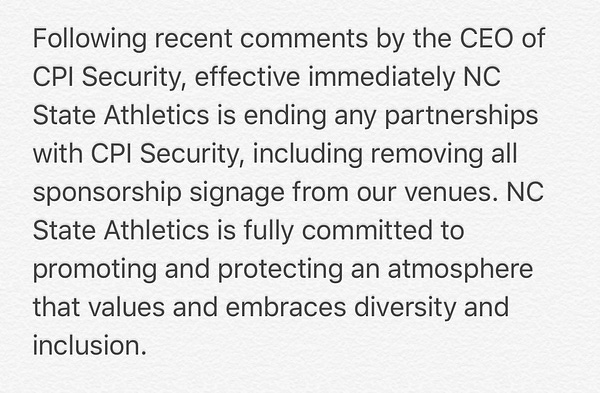

On June 7, 2020, NC State announced it was ending its partnerships with the Charlotte-based security company CPI Security for stated reasons pertaining to diversity and inclusion, as part of a decision that included the removal of all sponsorship signage for CPI Security on campus. The Charlotte Observer reported that Queen City Unity leader Jorge Millares “called for action in response to killings of black people such as George Floyd by police” in an open letter, to which CPI Security CEO Ken Gill responded:

George,

Please spend your time in a more productive way. I challenge your statistics.

A better use of time, would be to focus on black on black crime and senseless killing of our young men by other young men.

Have a great day.

Ken Gill

Queen City Unity then started a boycott of CPI Security and The News & Observer reported that the Carolina Panthers, Charlotte Hornets and the University of South Carolina were among the organizations and professional sports franchises that ended their relationship with CPI Security.

“NC State Athletics is fully committed to promoting and protecting an atmosphere that values and embraces diversity and inclusion,” read part of the university’s statement. Out of Bounds filed a public records request for a copy of any contracts between NC State and CPI Security but a university records officer said the partnership was through Wolfpack Sports Properties, LLC, which means the university doesn’t have any responsive records.

After the university’s announcement, NC State Senior Associate AD for Communications and Brand Management Fred Demarest sent Athletic Director Boo Corrigan a draft of a letter addressed to “Partners of NC State Athletics,” which was followed by the draft of another letter that was going to be sent to Gill and CPI Security.

Corrigan asked for Demarest to add something “about caring about our partners and their commitment to NC State as well as the current (situation-need a better word). We care deeply about our brand halo and want [to] be able to walk hand in hand with our sponsors now and into the future. When we see something out of alignment we will act…”

Below is the draft that Demarest wrote for Corrigan to send to CPI Security and its CEO Gill.

On the evening of NC State’s announcement, an executive at a real estate company sent Corrigan an email with the subject line “My sad day!”

“Boo,” the executive wrote, “I agree with the position of the CPI CEO. I guess this may end my contributions to NCState [sic] University & Athletics!”

The executive wasn’t just a (potentially now-former) donor to NC State, but the executive is also a former standout athlete at NC State who later worked in roles associated with the university.

This is one of the Wolfpack’s own.

When Corrigan forwarded the executive’s email to Vice Chancellor for University Advancement and President of the NC State University Foundation Brian Sischo, Sischo responded, “I also have some thoughts.”

By NC State cutting ties with a corporate sponsor whose president and CEO made racially insensitive comments in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd, the university’s athletic department may have also lost the support of one of its more decorated athletes and someone who had previously worked for the school.

Wins and losses can determine how big, or how public, alignment issues become

247Sports reported in December that many University of Texas donors threatened to end their contributions to the university, including one seven-figure donation, if the school’s football players didn’t stay on the field to stand for the singing of the university’s alma mater, “The Eyes of Texas,” which athletes at the school had asked to be replaced “with a new song without racist undertones” in a public letter written last June, given the song’s association with minstrel shows.

In October, Dallas News reported that now-former Texas coach Tom Herman was “threading a verbal needle” between supporting his players and satisfying the fans who wanted the players to show a reverence toward the school’s alma mater.

Six days after the Capitol was stormed, the University of Kentucky men’s basketball team, including coach John Calipari, knelt during the national anthem, prior to Kentucky’s game at Florida. It was the players’ idea.

“It’s just a peaceful way to protest and raise awareness … of things that have happened recently,” Kentucky’s Olivier Sarr said.

The Courier-Journal reported on the backlash that the university faced after the Florida game:

The sheriff and jailer in Laurel County posted a video to Facebook of them burning UK T-shirts. The Knox County Fiscal Court adopted a resolution asking Gov. Andy Beshear and members of the state legislature to reallocate tax funds given to the University of Kentucky in response to the team's protest. Kentucky Senate President Robert Stivers, R-Manchester, delivered an emotional address Monday night on the Senate floor, saying he was "hurt" by the team's actions because of his family's ties to the military.

Calipari said of his players’ idea several days after the game, “This political time, probably not a real good time to do it.” He continued: “Hopefully going forward we're going to figure out and help them have some actions that are not in front of the public, that are not in front of the TV, but things they can do to bring people together or make a difference."

Like Herman, Calipari appeared to try to pull off a delicate balance between supporting his players, who came to him and asked him to kneel with them, and appeasing Kentucky’s fan base at large.

While there are some general similarities between the two situations, ESPN’s Bomani Jones has pointed out that the reaction from many Texas fans to the school’s football players not supporting “The Eyes of Texas” is similar to the reaction of many fans when athletes kneel for the national anthem, except “The Eyes of Texas” is not the national anthem; it’s just a song with an unseemly past that’s sung to the tune of “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.”

After Texas started the fall with a 2-2 record in a season that culminated in Herman’s firing, and after Kentucky got off to its worst start to a men’s basketball season since the 1927 season, public spats over Respecting Tradition or The Troops can boil over as, once again, players are often asked to show deference, or respect, or appreciation, or obedience to fans who provide some level of money to their university and then expect something in return.

It’s political capital – typically metaphorically political, but it can also be literally political, as leaders in Kentucky’s Knox County and the state’s senate president showed – and that political capital can certainly affect the spending of financial capital, which is used for season tickets and contributions to athletic departments for coaches’ salaries, facilities and scholarships. Maybe even a learning center.

It’s the heartbeat of college athletics.

To try to quantify the value placed on various sports and skills within college athletics, I recently analyzed the online biography for every Power 5 athletic director, and in total, a dollar sign appeared just three fewer times than the sport of basketball. “Fundraising” was mentioned only five fewer times than soccer and 15 more times than tennis. It’s not a new development that fundraising is critical to college athletics, but it feels especially important during the pandemic and as athletic departments plan for the future.

In the University of Tennessee’s recent press release that announced the hiring of new Athletic Director Danny White, under a subheading that read “Winning with Integrity,” the last sentence of the first paragraph read, “He has also been successful in raising funds to improve the quality of athletic facilities.” Whether the evidence is anecdotal from a press release about one high-profile athletic director or whether it comes from an 87,000-word analysis of 65 athletic director biographies, it appears there’s an additional emphasis placed on fundraising and improving facilities.

In the current era of college athletics, taking a stand for something you believe in might shut off a six or seven-figure valve, and fundraising might sometimes require the extension of an olive branch made out of $100 bills, or the building of bridges that are constructed out of blank checks, all in order for athletic departments to solicit contributions from boosters who might disagree with the performance or the politics of the university, its administrators, its coaches or even its athletes.

In exchange, donors will probably expect a “thank you,” and sometimes much more.

Recap of the last newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“In relation to the Championship Arc, Gonzaga and Baylor both currently stack up as favorably as almost any Final Four team since 2002, while the next-best teams – Villanova, Michigan and Iowa – are on the edge, or just outside, of the arc.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.

Excellent article, Andy