An examination: To what degree will NIL deals affect athletic department revenue?

A closer look at the food and beverage, auto, travel, banking and insurance industries, and their relationships with NIL

Welcome back to Out of Bounds, a free, weekly newsletter about college athletics. Feedback, tips and story ideas are always welcome at andrew [dot] wittry [at] gmail [dot] com or you can connect with me on Twitter.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, you can subscribe for free below.

Last week’s newsletter detailed my attempts to obtain redacted name, image and likeness (NIL) disclosure forms through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, which generally and predictably resulted in most of the requests being denied under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). The purpose of the requests was to learn more about the types of NIL opportunities and offers available to college athletes, while still complying with state and federal laws to protect educational records and student privacy.

After last week’s newsletter was published, I have since obtained additional redacted disclosure forms that were submitted to universities on July 1. The disclosures I’ve obtained so far are listed below in descending order of compensation, which is listed in bold font.

University | Type of NIL activity | Frequency | Sponsor/Industry | Compensation

Texas Tech | Social media post(s), merchandise, personal content creation, personal appearance, autographs, business venture, endorsements, lessons and camps | “Years” | N/A | $1,000

Texas Tech | Social media post(s), endorsements | “When” | N/A | $1,000

Nevada | Social media post(s) | “Post on my Instagram story every so often” (the duration of the agreement is from July 1 through December 1, 2021) | N/A | $250 per month in online store credit

Texas Tech | Social media post(s) | Redacted | Telecommunications | $45

Texas Tech | Personal appearance | “Based off demand” | N/A | $40

Texas Tech | Social media post(s) | One time | N/A | $30

Texas Tech | Personal content creation | Redacted | N/A | $30

Texas Tech | Social media post(s) | One time | N/A | $30

Southern Miss | N/A | N/A | Apparel | $9

Eastern Washington | Social media post(s) | One time | YOKE Gaming | $3

Texas Tech | Lessons and camps | “Every day” | N/A | N/A

Texas Tech | Social media post(s), merchandise | “Different times when clothing releases” | Apparel | N/A

Texas Tech | Social media post(s) | “1st a month post” | N/A | N/A

While once again acknowledging the limited sample size of this analysis, many of the NIL activities and opportunities disclosed by current college athletes are related to their social media accounts or personal brands, whether they’re connected to the apparel and merchandise industry, or a tech-based sector, such as gaming.

How much overlap might there be between the sponsors of athletes and athletic departments?

While granting athletes their NIL rights is new to the NCAA and its member schools, it’s obviously not new to athletics as a whole, and the Olympics are one potential precedent to look to for historical context. That context says that college athletes could actually add value to college athletics at large by reaching new brands and consumers, rather than cannibalizing existing sponsorship agreements.

“We’ve seen this ecosystem develop in the Olympic world and develop in a way that builds beneficial [relationships], not just to the athlete, but also to the rights holders with whom they work,” Darryl Seibel, a founding partner at Stadion Sports, told Out of Bounds earlier this year, “whether that’s the national governing body, their national Olympic committee, groups like that – all, of course, subject to team-member agreements and things like that – so [as far as] misperceptions or misconceptions out there, one is, I think, the idea that empowering athletes could somehow dilute the value of other rights.

“Completely disagree with that. I think what you’re going to see is athletes become more empowered and in a position to manage and market their own NIL. It’s actually going to create greater value across the entire ecosystem. That athlete will have an ability to speak to consumers that a rights holder may not ordinarily or automatically get to on their own. We’ve seen that in the Olympic world. Athletes will connect with brands and in so doing, can connect with consumers that your traditional rights holder may not get to and they’ll establish a relationship with those brands and consumers that actually creates greater value for everyone.”

The long and the short of Seibel’s observations from the Olympic world is that many, if not an overwhelming majority of college athletes will find opportunities with different segments of companies or industries than those who sponsor their school’s athletic department. In reporting last week’s newsletter, I found that an athlete at Eastern Washington University disclosed one potential NIL deal with YOKE Gaming that would be worth just $3, which would be paid via Venmo or another electronic payment service, and I obtained another redacted disclosure form submitted by an athlete at Southern Miss, who was offered $9 for an apparel endorsement.

Those offers represent the low end of available NIL deals and the entity that manages the media rights and sponsorship licenses for your local Division I institution’s athletic department may not pursue sponsorships unless their value reaches a factor of at least 100 times the size of those entry-level NIL deals.

Let’s all remember the memes inspired by ‘MSU Spartans Presented by Rocket Mortgage’

Remember when Michigan State announced in March that “under the new five-year deal, Detroit-based Rocket Mortgage will be the presenting sponsor of the famed men's basketball team which will now be known throughout the Breslin Center as, ‘MSU Spartans Presented by Rocket Mortgage’”?

The bold font was theirs, not mine, by the way.

The announcement led to some good jokes on Twitter, some fair critiques of the system at large (then-Michigan State guard Rocket Watts and his teammates were unable to monetize their NIL rights at the time), as well as a brief, next-day addendum from Michigan State to the original news release.

“Michigan State is not renaming its men's basketball team,” stated the first line of the follow-up statement.

At the time, I filed a FOIA Request Presented by Andy Wittry for a copy of Michigan State’s contract with Rocket Mortgage and I was told by Michigan State’s FOIA officer that no responsive contracts exist. Michigan State has a contract with FOX Sports College Properties, which negotiates the university’s multimedia rights and sponsorship licenses on the athletic department’s behalf, so FOX Sports College Properties has possession of the contract with Rocket Mortgage rather than the university itself.

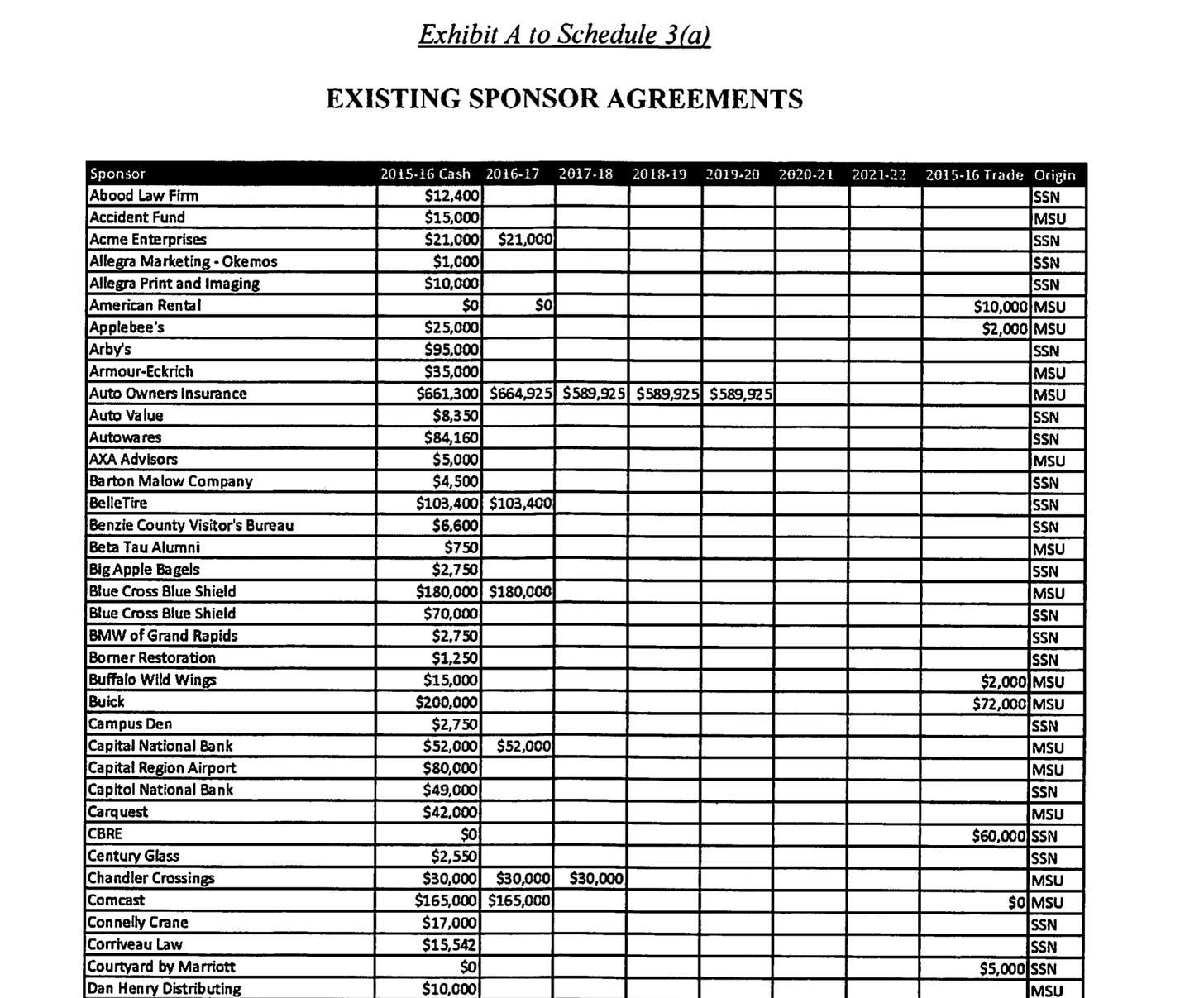

But I did obtain Michigan State’s contract with FOX Sports College Properties, which was effective as of July 1, 2016, and includes a three-page exhibit of the athletic department’s existing sponsor agreements, prior to when it signed a contract with FOX. The list includes the names of sponsors and the cash or trade value for each remaining year of each sponsorship.

This list of sponsorship agreements could come in handy because now that college athletes are allowed to monetize their NIL rights, questions have been asked about if, and to what degree, NIL deals for college athletes will impact athletic departments’ annual revenue, if NIL opportunities potentially result in decreased sponsorships or contributions for departments. I’ve been asked this question during appearances on radio shows and it has been floated by numerous administrators and media members.

As a one-school test case, I thought it’d be interesting to compare Michigan State’s existing sponsors, circa the 2015-16 school year, with the sponsors of college athletes through the first three weeks of July. After providing all of the necessary disclaimers – this is only one school’s sponsors, it’s not necessarily an exhaustive list of its sponsors, many of the sponsorships listed in the exhibit are up to five years old, the NIL market is nascent, there’s not a comprehensive list of every NIL opportunity that college athletes have pursued so far, etc. – I was curious, just how much overlap is there potentially between one Power 5 athletic department’s past sponsors and those of current college athletes?

Also, here’s some quick legalese from Michigan State’s contract with FOX Sports College Properties about the financial arrangement between Michigan State’s athletic department, its sponsors and FOX:

TL;DR: Michigan State doesn’t exactly pocket the agreed-upon value of each sponsorship, given that FOX negotiates sponsorships on the school’s behalf and it only pays out a specific, annual fee to the school, as well as a percent of all revenue that’s above a specified benchmark.

The revenue from these sponsorships “shall be assigned to FOX and to the extent not paid directly to FOX by Existing Sponsors, credited towards the Annual Fee,” according to the contract.

Under the terms of Michigan State’s contract with FOX, FOX agreed to pay $158.9 million in annual licensing fees to the university over the lifetime of the 17-year contract, starting at $6.875 million in the 2017 contract year and peaking at $11.25 million in 2033.

FOX also pays the university 40 percent of the royalty revenue it generates that’s in excess of the annual revenue benchmark that the two parties have agreed upon. The benchmark increases over the course of the contract term from $9 million in the first contract year to $19.6 million in the final contract year.

Your local Power 5 athletic department might have as many national food and beverage sponsorships as there are total national food/bev sponsorships for college athletes

After sorting the existing sponsors of Michigan State’s athletic department from the 2015-16 academic year that are listed in its contract with FOX, and after also compiling a very incomplete list of NIL deals I’ve observed (I’ve been traveling and generally away from social media, so emphasis on “very incomplete”), the most common industry of potential sponsorship overlap appears to be the food and beverage industry.

While several notable college football players have signed deals with regional or national brands, such as Oklahoma quarterback Spencer Rattler with Raising Cane’s, LSU quarterback Myles Brennan with Smoothie King and LSU cornerback Derek Stingley Jr. with Walk-Ons, a local college town hotspot seems to be more likely to sponsor a college athlete than a major, national chain. And that’s the type of food and beverage entity that was responsible for the bulk of Michigan State’s existing food and beverage sponsorship revenue in 2015-16 – restaurants, beverage providers and grocery stores such as Pepsi ($385,000), Meijer ($190,000), MillerCoors ($150,000), Tim Hortons ($97,240) and Arby’s ($95,000).

Plus, if a national brand or chain such as Pepsi or Arby’s does sponsor a high-profile college athlete, such as one who happens to attend Michigan State, that decision wouldn’t necessary affect Michigan State’s athletic department revenue, if it’s Arby’s corporate office that’s making that type of marketing decision.

It’s also worth a reminder that under some state laws that pertain to athlete compensation, as well as NIL policies that exist at individual schools, alcohol-related NIL activities are often prohibited, so many athletic departments can engage in sponsorships with major beer distributors, while the closest deal to the alcohol industry that many athletes can potentially strike is probably a local bar and grill. Plus, given the ages of college athletes, many athletes aren’t even of legal drinking age.

(For what it’s worth, the Beer Institute’s advertising/marketing code and buying guidelines state that while models and actors who appear in beer advertising and marketing materials should be at least 25, “for the avoidance of doubt, generally recognizable athletes, entertainers and other celebrities who are of legal drinking age are not models or actors under this provision, provided that such individuals reasonably appear to be of legal drinking age and do not appeal primarily to persons below the legal drinking age.”)

Similar to alcohol, many state laws and individual university policies regarding NIL have clauses that prevent NIL activities related to gambling, so athletic departments likely won’t have to worry about college athletes infringing upon the status of future sponsorships such as Michigan State’s previous sponsorship deals with the Michigan Lottery ($364,280 in 2015-16) or Soaring Eagle Casino and Resort ($90,000).

Let’s talk about the local car dealership and why that meme could turn out to be a bit overstated

It’s a bit of a trope in college football circles to talk about the potential impact that boosters who run local car dealerships can have on their respective local football programs, and there’s certainly some degree of truth and reality behind it.

But all of the speculation about how dealerships are going to hook up star athletes with luxury cars or four- and five-figure appearance fees to appear in some meme-worthy local car commercials could prove to be a bit overstated. That prospect isn’t necessarily going to drain athletic departments’ sponsorship revenue, especially when considering just how many sponsorships athletic departments can have related to the automobile, transportation and travel industries.

University of Miami quarterback D’Eriq King announced a deal with Murphy Auto Group on July 1, so you can put a chip on the “Star QB signs with car dealership” square on your NIL bingo card, but anecdotally, the retail, apparel, and food and beverage industries seem to be responsible for a larger number of sponsorships for college athletes thus far.

Here’s a list of all of Michigan State’s sponsors related to the automobile, transportation and travel industries during the 2015-16 academic year.

(Click or tap the image below to open in a new window)

The college football season will likely give us at least one or two entertaining NIL storylines related to local car dealerships, but if the fat part of the bell curve for NIL opportunities, in regards to compensation, falls somewhere in the $50 to $500 range, then car dealerships might turn out to play a smaller role than many imagined.

Speaking of which, in what other industries might athletic departments have a sponsorship stronghold?

While Tennessee wide receiver Grant Frerking, himself a CEO of a landscaping company, signed a sponsorship with Capital City Home Loans due to a connection with one of its mortgage consultants who is a friend from high school, banks, credit unions and financial advisors can have six-figure sponsorships with athletic departments. A potential sponsorship with college athletes who are teenagers or 20-somethings, who likely only recently took charge of their own finances, may not offer those financial institutions the same value or target audience as a partnership with a university, which has dedicated in-person and television audiences of young alumni, parents of current and prospective students, and boosters.

Maybe campaigns targeted toward college students who are in need of student loans or new bank accounts could lend themselves to athletes as spokesmen or spokeswomen, but Instagram or TikTok may not be the venue to reach the fans with the most money.

The same theory could potentially apply to many insurance or medical providers. On Wednesday, StreetInsider.com reported that car insurance company Clearcover “is the first auto insurance company to support individual student-athletes in the NIL era,” two weeks into said era.

Among the 137 existing sponsors listed on the exhibit within Michigan State’s agreement with FOX Sports College Properties, 52 sponsors agreed to an annual sponsorship rate greater than $30,000, which was a rough goal post for the high end of the NIL deals signed on July 1. Only three of the existing Michigan State sponsorships for the 2015-16 academic year were worth less than four figures, and there’s a case to be made that for athletic departments to lose a significant amount of revenue directly due to their athletes’ NIL activities, they’d potentially have to get nickeled and dimed by a series of small and mid-level deals, rather than individual athletes single-handedly cannibalizing five or six figures’ worth of companies’ marketing budgets.

Here are some of the different brands and audiences college athletes can reach

When athletes like Oregon defensive end Kayvon Thibodeaux, or quarterbacks such as Miami’s King or Florida State’s McKenzie Milton announce their plans for non-fungible tokens (NFTs), those avenues for earning potential won’t directly take away from existing sponsorships that their athletic departments might have. (Although, Stephen F. Austin minted an NFT in honor of its women’s basketball team’s conference tournament title in the spring and other athletic departments could potentially follow suit as they look to recover financially from pandemic-related losses in revenue.)

Apps such as Cameo, where users can pay for personal, video shoutouts from celebrities and public figures, or YOKE Gaming, which allows fans to play video games with athletes, have been recurring figures early in the NIL era. Users of apps that offer athlete-to-fan engagement are likely interested in those offerings largely due to the popularity and personal brand of the individual. They’re like an à la carte option for fans and brands that want to engage with or sponsor an athlete, but that may not have the budget, marketing campaign or interest to pursue the entire team or athletic department.

Michigan State kicker Matthew Coghlin’s recent tweet about the Locked On Spartans podcast that covers Michigan State garnered more than 1.1 million impressions on Twitter within the first 36 hours and the cost of that type of sponsored social media post could fall within the $30 to $100 range, depending on the athlete and the size his or her following. While Michigan State’s athletic department’s existing sponsorships during the 2015-16 academic year included companies in the media industry, they were larger outlets, such as the Lansing State Journal and SiriusXM. Coghlin also promoted friend of the newsletter Matt Brown’s newsletter, Extra Points, which has sponsored several college athletes, including Illinois women’s soccer and track and field athlete Abby Lynch, and Parker Ball, a walk-on offensive lineman at Tennessee.

Iowa men’s basketball player Jordan Bohannon’s one-time promotion of fireworks store Boomin Iowa Fireworks might make more business sense in that seasonal industry rather than a fireworks superstore’s hypothetical months- or year-long promotion through an athletic department, which typically has few, if any, of its teams in action when Americans are usually buying fireworks.

After Dan Lambert, a Golden Cane booster for the University of Miami and the founder of the MMA gym American Top Team, committed more than half a million dollars per year to sponsoring the university’s scholarship football players, he told Sports Business Journal he is unsure if he would continue donating to the athletic department.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I need to see what kind of return we get.”

Return could be defined in two ways, from both a business perspective for American Top Team and in the on-field success of the Hurricanes, given Lambert’s involvement in the “Bring Back the U” movement, which is built around a company whose mission is “helping the University of Miami football program reestablish its tradition of greatness.”

Athletes and athletic departments can offer different value to different companies in different industries, so college athletics – as an industry of its own – could see greater value across the board in the NIL era through connections with new brands and consumers, just as the Olympics have. But if boosters, such as Lambert, really do see a better return – on or off the field – by investing directly in athletes rather than through donations or sponsorships to the athletes’ athletic department, then the potential losses in athletic department revenue could theoretically lead to more wins, too.

The financial concerns within athletic departments are understandable, especially after they faced pandemic-related losses in revenue, and now it’s college athletes’ opportunity to cash in, amidst the backdrop of many Power 5 athletic departments’ reported annual revenue having roughly doubled since the late aughts.

In case you missed the last newsletter

(Click the image below to read)

“New Mexico State is an FBS independent in football, so while it’ll play schools like Alabama and Kentucky this fall, it operates on a different plane within the NCAA’s Division I populace in terms of revenue and fan interest compared to the Crimson Tide and Wildcats. And yet, 7.8 percent of the respondents – four out of the 51 New Mexico State athletes who filled out a disclosure form – said that as of July 1, they are engaged in NIL activities. If you include the aspirational Aggies who indicated that they intend on engaging in NIL activities, that figure grows to 25.5 percent.”

Read the full newsletter here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Out of Bounds with Andy Wittry. If you enjoyed it, please consider sharing it on social media or sending it to a friend or colleague. Questions, comments and feedback are welcome at andrew.wittry@gmail.com or on Twitter.